Boom and Bust: Creating a North Dakota History Game to Teach High School Economics

What if your next economics lesson didn’t start with a textbook, but with a dice roll? When a local teacher reached out asking if I had any lessons related to economics for a class of high school students, I saw this as a perfect opportunity to make history relevant and engaging for young people. Thus was born a project combining state history, economic theory, and game-based learning into a hands-on classroom experience. The result was a game exploring the agriculture and oil booms and busts of northwestern North Dakota between 1975 and 1985.

Why then? The late 1970s and early 1980s were a time of dramatic economic swings in our region. High oil prices and strong wheat markets brought prosperity to many communities, followed by sharp downturns that left lasting impacts. These cycles of boom and bust offer a powerful lens for teaching key economic concepts like supply and demand, market speculation, and resource dependency.

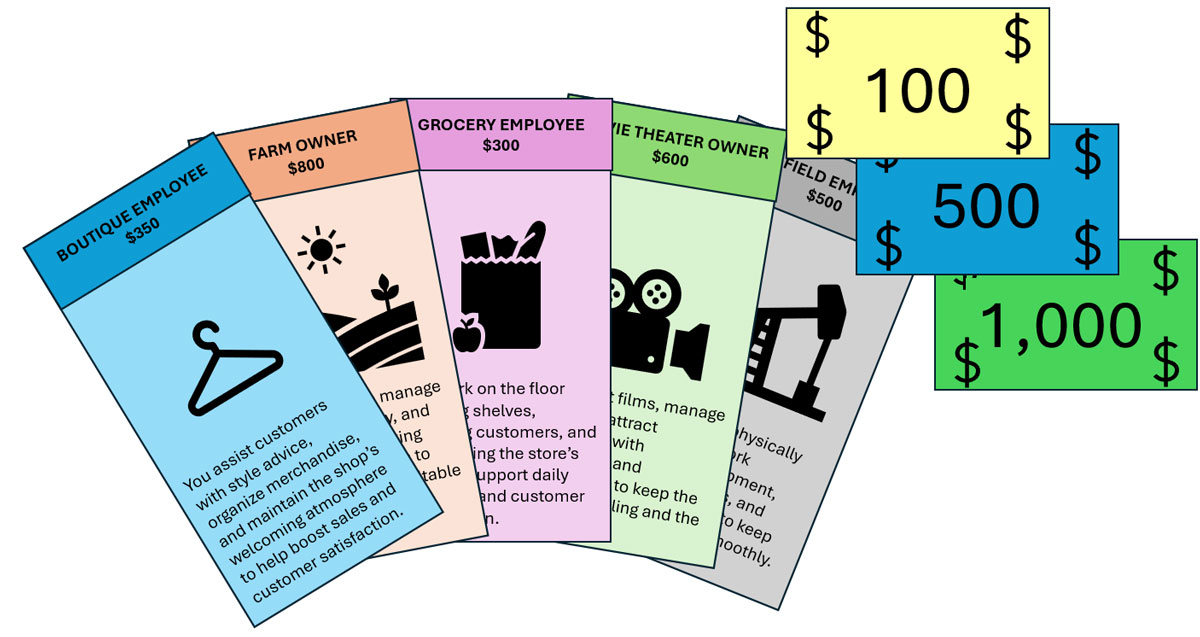

Career cards describe each community member’s job role and salary. Play money is used for transactions in the game.

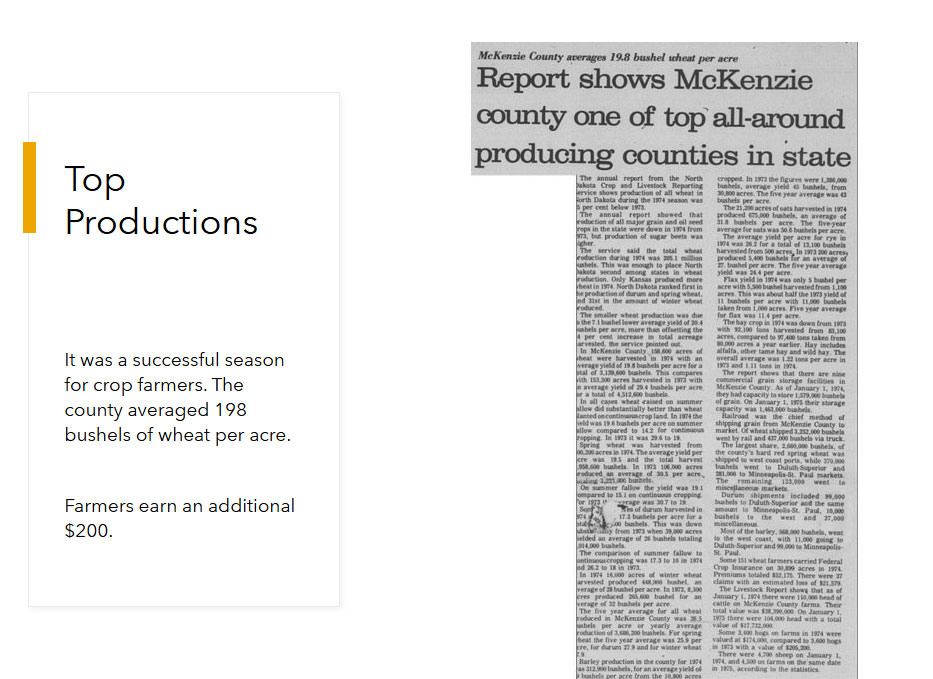

In this economics game, students assume jobs in the community such as teacher, rancher, or oil worker. Then they roll the dice to advance the game and determine the fate of that group. Each game square represents an event inspired by real newspaper clippings from McKenzie County. Each round is a year between 1975 and 1985. Players must make decisions about investing in oil rigs, expanding farms, buying insurance, and building infrastructure, while navigating unpredictable market shifts, weather events, and policy changes.

Game squares contain a newspaper clipping and detail the impact the report has on careers in the game.

By the end of the game, students have gained an understanding of how history and economics intersect in their own backyard and grappled with the challenges of economic decision-making under uncertainty.

Through this game, students don’t just learn about economics, they live it. By stepping into the shoes of real community members and navigating the volatility of boom-and-bust economies, they gain a deeper appreciation for how market forces shape lives, towns, and futures. It’s a powerful reminder that history isn’t just something we read about, it’s something we can simulate, question, and learn from. In doing so, we help students connect classroom concepts to real-world stories rooted right here in North Dakota.