1. That’s made out of butterflies?

Friend to gardeners, ecotourists, and second-grade science projects, the butterfly is the flagship for biodiversity in your front yard. Butterflies are an essential part of the food web and plant pollination. And artwork, it turns out.

Look closely at this portrait and you will see it’s not just a silhouette of a woman — the piece is made entirely out of butterfly wings.

2. The most dangerous animal in the museum is what?

When museum bloggers discuss dangerous animals, the usual suspects come to mind: bears, mountain lions, and venomous snakes are certainly to be respected in the North Dakota wilderness. Relatively few people think of the bison, which was perhaps the biggest killer of humans even 500 years ago. Imagine being part of a hunting party, crouching in the grass, while thousands of 2,000-pound bison, strong enough to plow snow with their faces, graze a few feet away from you. Horses were reintroduced to North America in 1519, and that made the bison hunt faster, but not necessarily safer.

The point is bison are tough. Our taxidermy mounts have been on display since 1925. Depending on your age, you might remember them from when the museum was housed in the Liberty Memorial Building, the ND Heritage Center & State Museum constructed in the 1980s, or as they are displayed today in the Innovation Gallery: Early Peoples. They are beautiful to appreciate, but it’s still advisable to keep your distance.

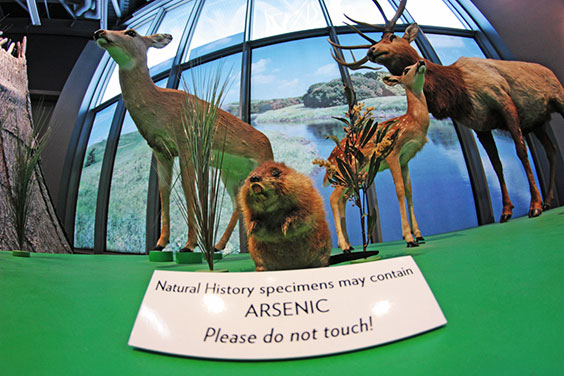

3. Why does your exhibit contain arsenic?

I am not a museum preparator or conservator. I don’t even play one on TV. But common sense tells me if the word “arsenic” is involved, it would be a good idea to keep my distance. Arsenic used to be a mainstay in industries like embalming, agriculture, and even cosmetics. It was also a champion bug killer, so it was used heavily in taxidermy until people realized that it wasn’t very good for your health.

Taxidermy specimens have a lot of uses for researchers and are great tools for interpretation and education. But when the sign says “don’t touch” — we really mean it.

4. Why do you freeze the artifacts?

Some things don’t come in the door dangerous; they just get that way over time. Silver nitrate film is a good example of when good things go bad. When State Archives staff open a box of old film and get a strong whiff of vinegar from the silver nitrate, they take action to preserve the negatives. This is done through digitization, scanning, and good, old-fashioned refrigeration.

Why store things in a freezer? Without cold storage, materials can deteriorate rapidly. Silver nitrate film can spontaneously combust, which is pretty high on the crisis scale. With cold storage, negatives can remain unchanged and accessible for many centuries.

5. Just how many guns do you have?

While museum security is not as exciting as actor Ben Stiller would have you believe, remember that what you see at a museum is only about 10 percent of the actual collection (there many reasons for that, but that’s another blog post). Most of the museum’s gun collection, for example, is kept in a gun vault. There are muskets, cannons, pistols, guns from 19th-century campaigns and both World Wars. There’s even a flame thrower in the arsenal. (When the zombies come, we’re ready.)