Teaching about Tipi Technology

Just take a walk through any of our galleries at the ND Heritage Center & State Museum, and you will notice countless connections between history and science. Highlighting these connections is one of my favorite parts of working at the State Historical Society. The most recent example I have been thinking about is the tipi.

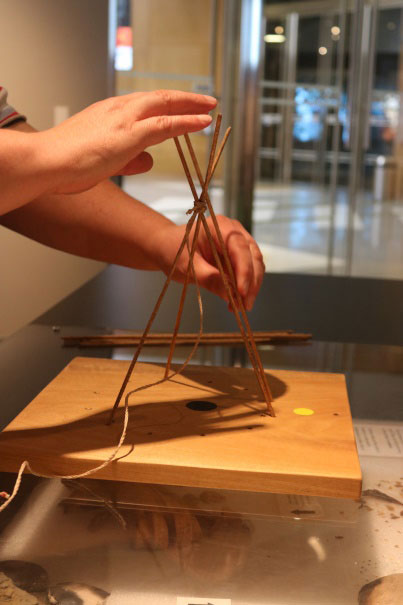

The tipi is an example of Native American science and engineering ingenuity at work. These cone-shaped homes are well designed for life on the open prairie. The main structure consists of three (a tripod) or four lodgepole pines lashed together with a sinew rope. The tripod is usually set up with one pole on the southeast to frame part of the door, while the other two poles are on the north and south sides respectively. After the tripod is situated, the rest of the poles are added in order so they lock each other in place. A tipi might have as many as eighteen or more poles to complete the structure. The door is usually located on the east side.

Outreach Coordinator Danielle Stuckle sets up a table-top tipi model during a public program.

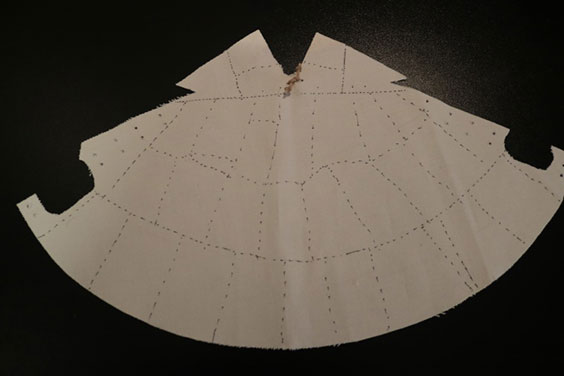

A tipi cover is made from either several buffalo hides sewn together or from a canvas. The tipi base isn’t a true circle, but is actually more of an oblong, egg-shape. This allows for the fire to remain directly under the smoke hole, yet moves it to the front of the tipi so there is more room for people to sit around the rear of the dwelling. This cone-shaped tipi on an oblong base is aerodynamic. As the wind moves over the structure, it pushes it into the ground and helps stabilize it. There is a slight tilt to the cone to enhance this effect. A tipi is brilliantly designed to stand up to the strong prevailing winds of the Great Plains.

This canvas from the table-top tipi model shows how several buffalo hides are sewn together to make a tipi cover.

A tipi is lined throughout with an ozan, or dew cloth, made out of hide, canvas, or blankets. This liner only goes up about six feet from the ground. There is a gap between the liner and the cover, which creates a chimney effect. This produces a convection current that circulates air in the tipi and pulls smoke out through the opening at the top. The flaps around the smoke hole can be adjusted as the wind changes direction; much like the flue of the chimney can be adjusted. This helps draw the smoke out so that a fire can be used inside for cooking and for warmth. The dead air between the liner and the cover also helps to insulate the tipi and keep it warmer in the winter. Wood pegs are added to the tipi poles to help guide water down the pole, between the cover and the liner. The cohesive effect of water keeps rain water running down this path all the way to the ground and right out of the tipi. If rainfall is really heavy, a gutter or shallow moat can be dug around the tipi, ensuring the inside stays nice and dry.

This scale model of a tipi is used in education programs at the State Historical Society of North Dakota.

A tipi is a well-designed structure, built out of locally available materials, to withstand the unique conditions of the Great Plains. We might not initially think of technological innovations in the distant past as science, though Native Americans used observations and experimentation to build knowledge about corn breeding, animal behavior, weather patterns, geology, and countless other aspects of the natural world. When it came to engineering their homes, Native Americans observed what works in this environment and experimented with different methods to build a better house. Certainly a practical and scientific approach we can appreciate.