Summer is a fun time with people from different places taking tours of the archaeology lab and collections at the State Historical Society. But since not everyone can come visit us in person, let’s take a virtual tour. Today we will tour the processing lab.

The archaeology processing lab at the State Historical Society.

Archaeologists study the human past by looking at what people leave behind, including artifacts. Artifacts encompass any objects that people made, used, touched, or carried.

Artifacts are sorted into different sizes in the processing lab. This is called size grading. For large projects we use a machine, which looks a bit like a big, motorized sieve.

The size-grading machine in the processing lab is useful in the sorting process.

We separate different-sized artifacts so it is easier to sort these objects by material types like stone, pottery, seeds, animal bone, and shell. It is a little easier for the human eye to distinguish among different materials when everything is closer in size.

The objects in the trays below are size graded. These items are part of the archaeology hands-on educational collection. Although real artifacts, they have low provenience and were found out of context in dirt piles resulting from a road construction project. Provenience is exactly where something is found at a site. Those things found around an object—other artifacts or related features like storage pits or house walls—are the context. Both context and provenience are very important.

Trays of size-graded artifacts.

When archaeologists study artifacts they need to know the provenience and context. Provenience and context give the details and clues needed to piece together the backstories of people living in a certain place and time in the past. This is why archaeologists take careful notes, make maps, as well as photograph and record everything as they excavate. All the recording is to track provenience and context.

Most of the items on the trays in the processing lab are from Scattered Village (32MO31) and the modern city of Mandan. Scattered Village was primarily lived in by Mandan people from the late 1500s to around 1700. The current city of Mandan originated in the 1870s and now covers the site of Scattered Village. Even though we know what village and city the artifacts are from (the general location), we don’t know specifically where on the site they came from (the exact provenience) or what was around or near them (the context).

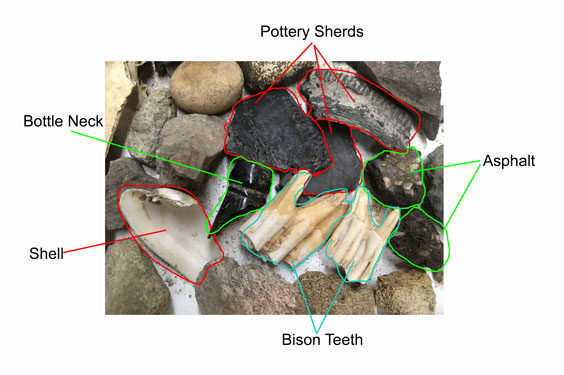

What do you see on the tray in this close-up photo?

Unprovenienced artifacts from Scattered Village and the city of Mandan.

If you look closely, you’ll see some recent artifacts, like chunks of asphalt from the road that was torn up to be repaired. There also are older items from Mandan’s early days, like an old glass bottleneck. Meanwhile, the bison teeth and pottery sherds from Scattered Village are around 300 to 450 years old. It’s unclear whether the freshwater mussel shell is from Scattered Village or Mandan since it is missing its provenience. Because these artifacts are missing their provenience and context information, they are not very useful for most researchers. But they are good examples of the types of materials and artifacts found at Scattered Village and in Mandan. They provide an opportunity for people to touch and see real artifacts when they visit the lab.

The artifacts revealed.

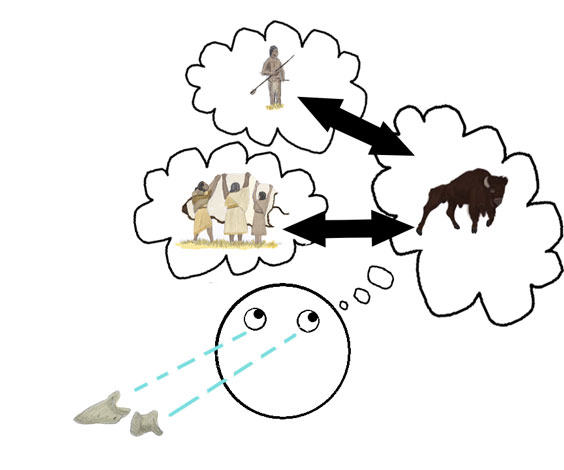

One of the reasons archaeologists sort everything into different material types is so each kind of material can be sent to people who specialize in the different materials. For example, all the animal bone found at a site will go to a faunal analyst (someone who studies animal bone). The faunal analyst will look at the bones and record what kind of animals they belong to. This can tell us about the environment at the time, the animals people hunted, ate, lived with or cared for, the age or health of those animals, and sometimes even the time of year an animal died.

A faunal analyst studies bones found at a site to identify the animals once living there and provide insight into both the surrounding environment and people’s interactions with the world around them.

Ultimately everything found during an excavation is examined and written up in a report so the information is available in the future to know more about the past.