“Do you take federal passes?” is a common question at the Lewis & Clark Interpretive Center and Fort Mandan State Historic Site in Washburn. Many of our visitors follow the Corps of Discovery’s route on the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, which begins in Pittsburgh and ends at the Pacific Ocean in Oregon. The popular trail is administered by the National Park Service (NPS) at the trail’s headquarters in Omaha, Nebraska. However, the trail itself is a cooperative network of sites and interpretive centers managed by various state, local, private, tribal, and federal entities. We are one of these.

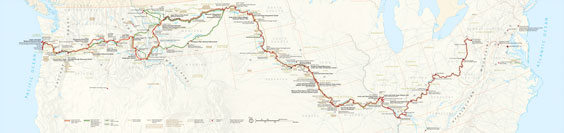

The National Park Service’s map of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail is available at all participating locations as a helpful travel aid and popular keepsake.

Federal locations include the Lewis and Clark National Historical Park in western Oregon and Washington. That park encapsulates NPS locations such as Fort Clatsop but also cooperates with Ecola State Park in Oregon and Cape Disappointment State Park in Washington. The U.S. Forest Service oversees the Lewis and Clark Interpretive Center in Great Falls, Montana, while the Bureau of Land Management runs Pompeys Pillar National Monument outside Billings. State sites include Travelers’ Rest State Park near Lolo, Montana, the only expedition campsite that can be archaeologically verified. Lewis and Clark State Historic Site in Hartford, Illinois, is a state Department of Natural Resources location across from the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. That site showcases the winter of 1803-4, which was spent preparing to ascend the Missouri River, and includes a replica of Camp Dubois, where the expedition stayed during this time. The state museums of Missouri, South Dakota, North Dakota, Montana, and Oregon are also on the national historic trail. The Sioux City Lewis & Clark Interpretive Center and the Betty Strong Encounter Center in Iowa and the Lewis & Clark Boat House and Museum in St. Charles, Missouri, are popular nonprofit institutions on the trail. North Dakota’s MHA Interpretive Center in New Town is one of many sites where Native Americans share their culture and history, which long predated the arrival of the expedition. We all work together to tell different parts of a whole story.

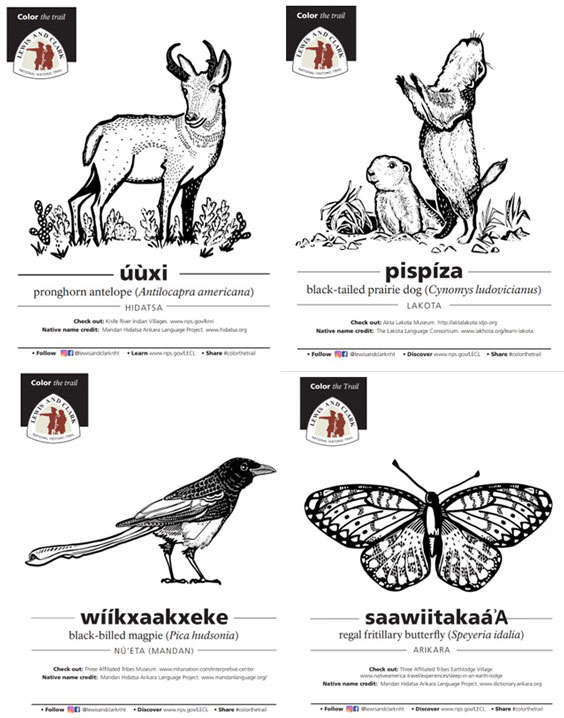

The “Color the Trail” series on the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail’s website highlights fauna encountered by the expedition with names in Indigenous languages. These coloring pages produced by the National Park Service are free at Washburn’s Lewis & Clark Interpretive Center and online.

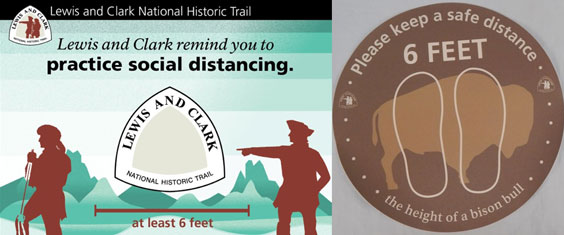

The Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail provides a wealth of resources. These have included social distancing signage during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, tactile maps with Braille labels, map handouts, coloring sheets with Indigenous animal names, and the award-winning Junior Ranger book. The Omaha office also promotes trail-wide messaging, which amplifies Native American voices and highlights conservation.

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail’s Omaha office provided social distancing signs and floor stickers for trail sites, which both entertained visitors and promoted public health.

Even Capt. William Clark enjoys the Junior Ranger program, which recently won the National Association for Interpretation’s prestigious Freeman Tilden Award. This asset from the National Park Service is a family favorite at the Lewis & Clark Interpretive Center in Washburn and other non-National Park Service locations along the trail.

Being an integral component of a culturally and geographically diverse national historic trail enables us to connect and learn. It generates great visitor interactions. Guests discover that Fort Mandan was shaped like a triangle, while Fort Clatsop was a rectangle. They compare earthlodges to tipis. And they may also notice that the spelling of the name of the Shoshone woman who assisted the expedition—Sakakawea, Sacagawea, or Sacajawea—reflects where they are along the trail. The trail takes the traveler through woodlands, plains, and mountains to arrive at the Pacific Ocean. I have traveled nearly all of it, although the 2019 extension to Pittsburgh has provided me with additional travel plans. It’s an amazing route to visit and work along.

Collaboration is a gift. At the local level, that can mean exchanging seeds with and borrowing supplies from the Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site, a nearby location on the trail. On a broader level, we communicate with colleagues at sites across the state and nation related to replica items and research. For instance, in fall 2022, my friend and lead interpreter at Lewis and Clark State Historic Site in Illinois, Ben Pollard, requested a soil sample from our area matching one collected by Meriwether Lewis on the Missouri River near the Fort Mandan State Historic Site. I happily obliged and dug sludge out from under the November 2022 blizzard’s leftover snow, letting it dry before packing it into a food container. While attending the National Association for Interpretation Conference in Cleveland later that month, I delivered it to Ben. The conference was a great time for staff from Lewis and Clark sites to meet up for lunch and coffee. We love visiting each other’s sites and comparing exhibits—or forts! As a member of the grant and outreach committees for the Lewis & Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, the trail’s nonprofit support group, I’ve also seen the vitality of visitor and employee connections from another angle. We are lucky to be on one of the nation’s premier national trails.

Ben Pollard of the Lewis and Clark State Historic Site in Illinois with Shannon Kelly and Dana Morrison from Washburn’s Lewis & Clark Interpretive Center in front of the Camp Dubois replica at the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation’s 2019 annual meeting.

To access educational resources related to travel, Indigenous languages, and history, visit Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail.