Do you remember your first childhood anatomy lesson?

“Dem bones, dem bones, dem dry bones…

The toe bone’s connected to the foot bone,

The foot bone’s connected to the ankle bone,

The ankle bone’s connected to the leg bone,

Now shake dem skeleton bones.”

An internet search shows many variations of this song. The only thing that doesn’t vary is the order of connectivity: toe to foot, foot to ankle, ankle to leg, and so on.

I don’t remember when I first heard this little ditty, but I have always been fascinated by bones. It may have something to do with being born and raised on a farm where I was constantly surrounded by animals and animal bones.

The galleries in the North Dakota Heritage Center and State Museum provide a perfect venue for the study of the structure and function of the skeleton and bony structures, also known as osteology.

I decided this fall that it would be fun and educational to write a short presentation on basic bone structure. After a couple of false starts, I enlisted the aid of a friend for a Saturday afternoon search and recovery mission for bison bones. That afternoon’s antics would provide enough material for a separate story, but suffice to say we loaded a pickup with dry, weathered bison bones, unloaded them in my garage (to my wife’s dismay), and I began the search for connectivity; toe to foot to ankle, etc.

Internet sites such as “The Virtual Museum of Idaho” made this a fairly easy project. The “American bison” page (UWBM-35536 -- Bison bison) provides full-color, 360 degree views of each bone of a bison’s skeleton.

Rearticulated bison front limb

With the reference site and a garage half-full of bison bones, some assembly was required. As luck would have it, we had acquired all of the bones on our search to rearticulate the left front leg of a bison. The assembled and properly labeled bones don’t lend themselves to a catchy tune, however:

“The third phalange connects to the second phalange,

the second phalange connects to the first phalange,

the first phalange connects to the metacarpal,

Now shake dem bison bones.”

As all projects seem to do, this one grew and began to take on an educational aspect that I had not envisioned when I identified the first weathered “calcaneus” bone. (Check it out on the Idaho Museum site.)

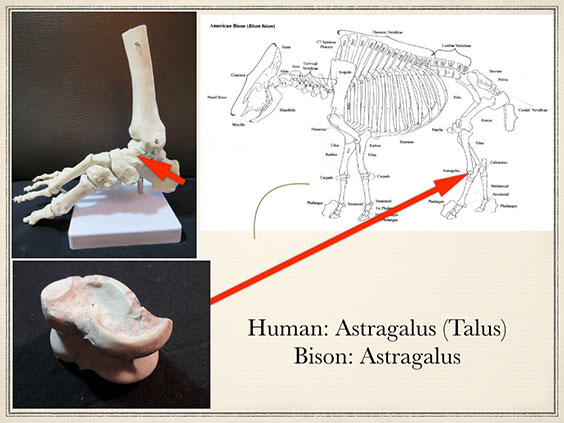

Slide from “Bison in A Box” presentation

The more bones that I reassembled, the more I realized how the bones of the front leg of a bison resemble and mirror bones of the human arm. A couple of purchases of a human skeletal hand model and human foot model clearly illustrated this. By this time, a Powerpoint presentation was beginning to take shape, and more bison bones began to fit together. With time, a complete hind leg of a bison was also rearticulated and my fascination grew—this time with the comparison between the “wrist” joints of a human and the corresponding “ankle” joints of a bison.

The North Dakota Heritage Center is a perfect venue for this presentation, where comparisons between the skulls of Bison latifrons and Bison antiquus, the ancestors to the modern Bison bison, are on display.

Bison antiquus skeleton, Innovation Gallery: Early Peoples

A full, life-sized model of the Bison antiquus is fully assembled (rearticulated) and helps illustrate the story of Beacon Island in the Innovation Gallery: Early Peoples. You, as a visitor to the exhibit, can hum whatever version of the bone song you prefer as you study this model.

The basic premise of bone identification has continued to evolve since I plucked that first bison bone from the prairie sod. My research has uncovered many uses for one of the newly discovered bones. The astragalus bone (one of the “ankle” bones of sheep, goats, bison, etc.) was used in Mongolian games of chance, was a useful component of friction fire-starting, and was the basis of a child’s game (“jacks”).

Join us at the Heritage Center as we continue to explore this bony topic and finalize our presentation, “Bison in A Box.”

If I could carry a tune a whole new genre of songs could be sung about bison bones:

“Astragalus connected to calcaneus,

Calcaneus connected to the tibia,

Tibia connected to the femur

And on and on it goes.”