A colleague at the ND Heritage Center recently recommended author Ross Coen’s Fu Go: The Curious History of Japan’s Balloon Bomb Attack on America, describing the relatively obscure World War II story of unmanned paper balloons flown from Japan to North America using only high-level atmospheric currents-- the jet stream-- as propellants. The ultimate goal of these balloon flights was to ignite forest fires across Western America and Canada that would create terror and divert potential military personnel to homeland firefighting.

Before hearing of this book, I knew nothing of this action. As I read it, I became more fascinated with little-known stories related to people of Japanese descent and their involvement (or not) in wartime activity.

Little did I know that this book would soon lead me to another little-known story of World War II, namely Japanese American internment. As I was finishing Fu Go a few months ago, I received a call from Dennis Neumann, public information director at United Tribes Technical College (UTTC). Dennis requested that I become involved in a project being organized by the National Japanese American Historical Society to develop a high school curriculum related to Japanese internment in America during World War II.

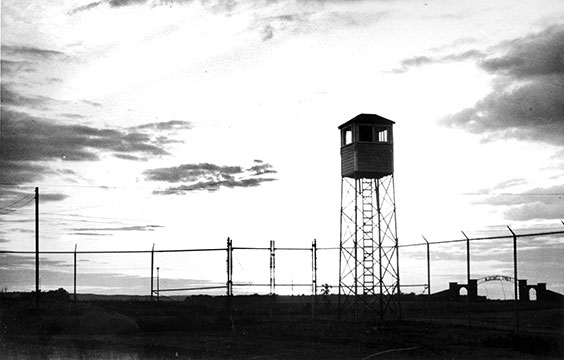

00996-00002 Fort Lincoln Entrance Gate

The National Japanese American Historical Society was forming a team to investigate national resources including historic places, stories, images, and other archival material in the visioning process for “Untold Stories: The Department of Justice Internment Teacher Education Project.” Few people realize that many Japanese American people were interned at a camp in Bismarck, North Dakota, during the war. This camp, called Fort Lincoln Internment Camp, was located on land that is now the site of UTTC’s campus, and some of those internment camp buildings remain.

00996-00002 Fort Lincoln Entrance Gate

The team of invited scholars, educators, and cultural interpreters from across the country came together for three days of presentations and discussion about this interesting topic. Their team of curriculum developers helped us consider how high school students across the country would find this story relevant. We discussed historical trauma, cultural suppression, and even bullying as we explored ways this topic might support cultural healing and recovery using public discourse. At the team meeting, I shared some of our State Archives resources including photographs, newspaper articles, and a diary kept by an internee at the internment camp. You can read “Internment Diary of Toyojiro Suzuki” (translated into English) at history.nd.gov/textbook/unit6_3_intro.html.

I also shared details of how content, activities, and resources related to our North Dakota Studies eighth grade and fourth grade curriculums are delivered online.

The outcome of this project will be a high school curriculum that may be available online. There was discussion relating to developing opportunities for teachers across the country to participate in workshops, visit the sites of the internment camps, and view documentaries relating survivors’ stories and the impacts to their families.

UTTC is interested in recognizing that the impacts of government policies relating to Native Americans such as removal, relocation, and the formation of reservations have many parallels to those of Japanese Americans interned at the same physical site during WWII. It’s a fascinating beginning to a project worth exploring further.