In 2000 historian Christian Warren published Brush with Death: A Social History of Lead Poisoning in which he introduced his construct of “toxic purity” relating to historic lead paint. Warren explains that in the early 1900s, US citizens (most well aware of the toxic nature of lead paint) still wanted pure lead paint—leaded paint with no adulterants or additives. When we think of lead paint today, we immediately associate it with the toxic side of this construct. Most consumers at that time, however, were worried about additional ingredients diluting the purity of lead paint.

One hundred twenty years ago consumers perceived lead paint to be the best. Consumers wanted to know the contents of the paint cans they purchased. If they contained ingredients such as water, benzene, chalk, or any oils other than linseed oil, many considered them to be inferior paints.1 There were no labeling laws; consumers did not even know the net weight of a can of paint. Although there were no standards set by industry or the government at the turn of the last century, consumers were hoping to purchase linseed oil thoroughly mixed with pure white lead powder and maybe some colorants.2

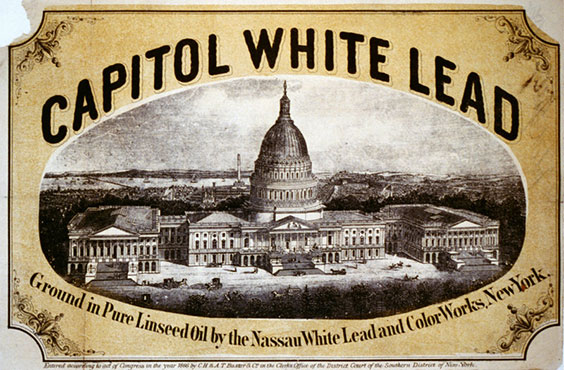

A label from one of many regional white lead paint producers. https://www.npr.org/2016/04/06/473268312/before-it-was-dangerous-lead-was-the-miracle-metal-that-we-loved

North Dakota was the first state to fully address informing consumers about the contents of a can of paint.3 In 1905 the state legislature passed “An Act to Prevent the Adulteration & Deception in the Sale of White Lead and Mixed Paints.”4 The legislature put the responsibility for carrying out this act on the capable shoulders of Edwin F. Ladd, the “fighting” chemistry professor at the North Dakota Agricultural College (now North Dakota State University), who also oversaw the publication of five bulletins on the subject of paint, its composition, and clinical tests of various brands of paints.

Historian Elwyn B. Robinson characterized Ladd as a zealous and courageous publicity seeker, outstanding in an era of progressive reformers.5 Ladd had already led the charge against food alteration at the college’s Experiment Station6, publishing his results in the station’s Bulletin 53. His work was important in the passage of the federal Pure Food and Drugs Act of 1906.7

In his introduction to Bulletin 67 on white lead paints, Ladd calmly informs paint manufacturers who want to challenge his results published therein to “let the courts decide.”8

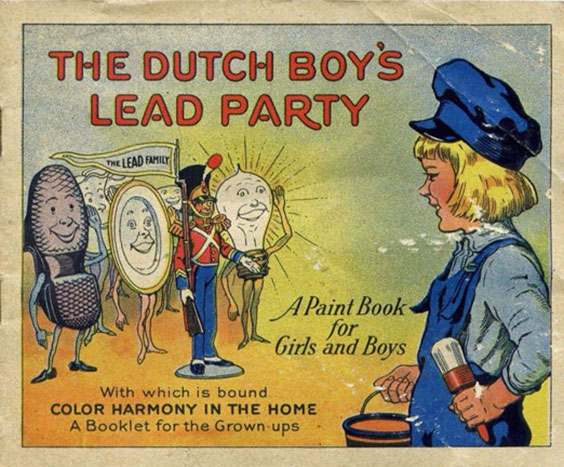

Dutch Boy logo and brand trademarked for the National Lead Company in 1907. Click the image to see the inside pages where happy children learned that lead was a most useful metal present in light bulbs, shoes, “tin” soldiers, baseballs, china, and other common household products.

In Bulletin 70 (1906) we learn the state court ruled in favor of the state’s right to regulate paint labeling. The Bulletin also provides the names of manufacturers who used up to 24 percent water in their paints, those who provided short weight adulterated or diluted lead in their paint composition, and those using up to 70 percent inert material, which was merely filler.9 In Bulletin 86 the Experiment Station analyzed many paints with mixed ingredients such as zinc oxide, a legitimate white lead substitute.10

At the time there were many small and regional paint manufacturers due to the cost of transportation of heavy ingredients. Ladd expected that manufacturers in the western half of the United States would provide inferior paints to those in the east, but found shocking results. Regardless of the region, “dope” paints were manufactured all over. North Dakota was the exception, as by the end of 1909 Ladd felt that the legal requirement to have truthful labels had greatly improved the quality of paint sold in the state.11

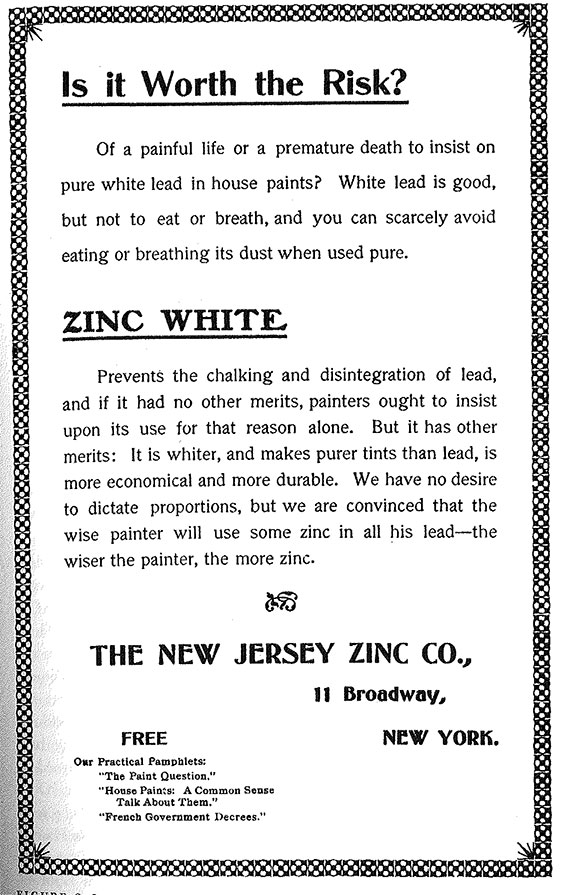

1903 Advertisement for the New Jersey Zinc. Co. We wonder if master painters and others knew about the toxicity of lead in the paints they used at the turn of the twentieth century. Yes they certainly did, better than we can know today, as they felt the agony of stomach ulcers, intestinal binding, tooth loss, gout, and arthritis. Some symptoms sent them to their beds for weeks waiting out “painters colic” if they (or more likely their apprentices) inhaled or ingested too much of the chalky powder. From Warren, Brush with Death, 61, and Olga Khazan, “How Important Is Lead Poisoning to Becoming a Legendary Artist?” Atlantic, November 25, 2013, https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2013/11/how-important-is-lead-poisoning-to-becoming-a-legendary-artist/281734/.

1 E. F. Ladd and C. D. Holley, “Paints and Paint Products,” North Dakota Agricultural College Experiment Station Bulletin 67 (1906): 575–77.

2 Christian Warren, Brush with Death: A Social History of Lead Poisoning (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000), 44–45, 52–53. The first ready-mixed paint came from Sherwin-Williams in 1880, but some master painters were still having their apprentices mix barrels of dusty white lead into linseed oil in the early 1900s. “The First Paint Revolution,” Sherwin-Williams, [accessed July 11, 2018, https://www.sherwin-williams.com/painting-contractors/business-builders/paint-technology-and-application/sw-art-pro-paint-revolution].

3 Warren, Brush with Death, 54. Nebraska passed a paint labeling law in 1902. It was backed by the lead-based paint manufacturers, who wanted to influence consumers to think of any new paint formulas that introduced new ingredients as inferior to lead paint. The labels did not require the disclosure of the amount of white lead.

4 Laws Passed by the Ninth Session of the Legislation Assembly of the State of North Dakota, 1905, Chapter 8 SB 49, 13.

5 Elwyn B. Robinson, History of North Dakota (1966; repr., Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009), 261.

6 https://library.ndsu.edu/ir/bitstream/handle/10365/23594/ndfr_19500501_v12_iss05_162.pdf

7 Warren, Brush with Death, 282.

8 Ladd and Holley, “Paints and Paint Products,” 575.

9 E. F. Ladd and C. D. Holley, “Paints and Their Composition,” North Dakota Agricultural College Experiment Station Bulletin 70 (1906): 53–65.

10 E. F. Ladd and G. A. Abbott, “Some Ready-Mixed Paints,” North Dakota Agricultural College Experiment Station Bulletin 86 (1909): 80–89.

11 Ladd and Abbott, “Some Ready-Mixed Paints,” 80–81.