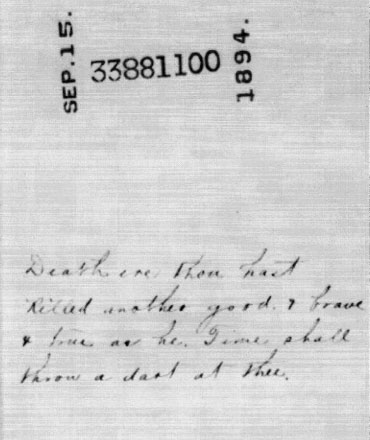

“An excellent soldier. A true man loyal, honest cleanly & of sweet disposition. Death ere thou hast killed another good & brave & true as he. Time shall throw a dart at thee.”

Company Descriptive Book

Fort Rice, Dakota Territory

May 11, 1865

What would prompt a hard-bitten file clerk at a desolate outpost in Dakota Territory to write the preceding eulogy for one young soldier?

We may never know the answer to that question, but the State Archives and a subscription-based internet military site reveal this and other stories of a band of “volunteer” soldiers in Dakota Territory.

The eulogy is an anomaly among the 24,000 military records I recently researched to gain a better understanding of 645 Civil War soldiers assigned to the 1st United States Volunteer Infantry (1st USVI). The regiment is probably better known as the “Galvanized Yankees.”

The story of how the soldiers came to occupy Fort Rice, a Dakota Territory military post named after a Civil War casualty, is too long to recount in its entirety here. Here is the short version: President Abraham Lincoln was forced to get creative in finding enough troops to fight on the fronts of two contemporaneous wars. The American Civil War was raging in the East and the aftermath of the US-Dakota War of 1862 was smoldering in the Midwest. To address the troop shortage, Lincoln made an offer to Confederate prisoners of war; in exchange for a vow of loyalty to the Union Army, he would send them to the Midwest to “subdue” the Native Americans instead of sending them back to the Civil War.

Many books, stories and articles have been written about the “Galvanized Yankees” at Fort Rice. For my purposes, though, a more thorough study of the individual soldiers was required. After slogging through the military records, I had a much clearer picture of the individuals and personalities involved.

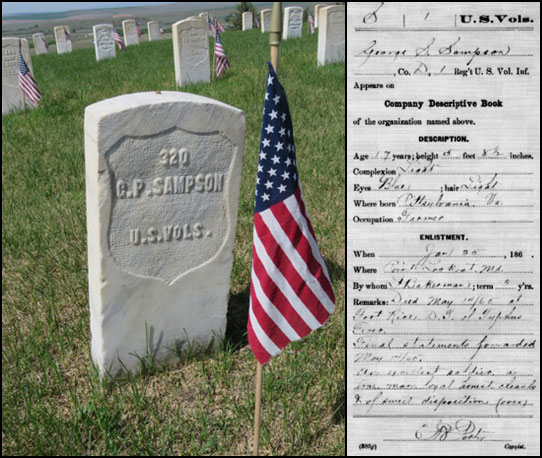

As with the eulogy to Private George Sampson of Company D at the beginning of this post, hints of their stories began to emerge. Private Sampson was a Virginia farm kid. He was described as being 17 years of age, 5 feet, 9 inches in height with blue eyes, light hair, and a light complexion. He died in the Fort Rice hospital on May 14, 1865, of “Typhus Fever.” Unfortunately, it is never revealed why he was singled out for such a unique epitaph and why his superior officer would paraphrase a 17th-century English poem in his honor.

Left: Private George Sampson’s headstone, Custer National Cemetery, Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument (Crow Agency, Montana). The soldiers, including Private Sampson, were disinterred from the Fort Rice cemetery in the early 1900s and reinterred at the Custer National Cemetery

Right: Entry for Private George S. Sampson, Company Descriptive Book, 1865

A composite image of the soldiers at Fort Rice is difficult to assemble. Some details, though, can be noted:

The soldiers, as in most wars, were young. They ranged from 14 to 51 years of age with an average of 24 years. Private Clinton Millsaps, also from Company D and another farm kid, was born in Tennessee. He was the youngest of the lot at the age of 14 and measured in at 4 feet, 10 inches tall, which was 2 inches taller than the Springfield muzzleloading rifle he carried. He also had blue eyes, light hair, and a light complexion. At the tender age of 14 he had several things in common with his fellow soldiers: he was already a veteran of the Civil War, he had served time in a Union military prison, and he had survived the trip to Dakota Territory. Unlike Private Sampson and 101 other individuals at Fort Rice, he would survive to return home after his regiment was disbanded. He served as a “musician” at Fort Rice, probably deemed too short to fight.

The majority of the soldiers at Fort Rice were illiterate, as evidenced by the “x” on the signature line of their Union army “vow of allegiance.” Privates Millsaps and Sampson signed their names to the papers; 337 other members of the regiment (52%) signed with an “x.”

The soldiers of the 1st USVI, the first permanent troops at Fort Rice, were mostly southern kids. They hailed from 19 eastern states, with North Carolina being the most represented at 269 individuals. The remainder of the regiment was populated by men from 20 foreign countries including Prussia, Switzerland, and Ireland.

Fifty-two different professions were embodied at Fort Rice. Their occupations included slaters, coopers, weavers and teamsters. The majority (457 of them) listed “Farmer” as their occupation prior to the Civil War. Despite their collective knowledge, agriculture at Fort Rice was mostly a failure. The grasshoppers were able to muster more troops than the army.

Many more stories were revealed in the archives, but my space has come to an end. The stories of desertions, drownings, “accidental” shootings, court martials, sentences of “death by musketry,” acquittals, deaths from various diseases, and even a couple of deaths at the hands of the Native Americans they had come to subdue must wait for another day.