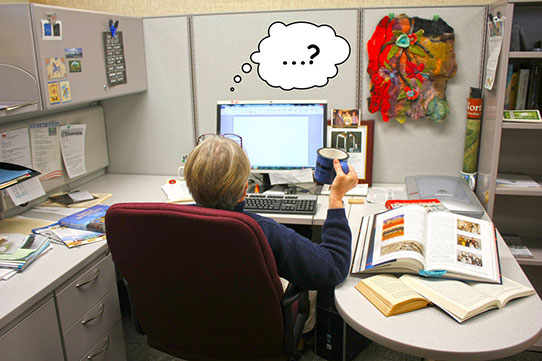

If, perchance, you walk past my desk one day, you might wonder: Does she work here? Not much sign of labor. Just a woman stretched out in a chair, staring at a computer screen.

Dr. Barbara Handy-Marchello works very hard at writing for North Dakota Studies. Rockeman photo.

I must say my work does not raise a sweat on my brow or pound callouses onto my fingers. If I go home with a bruised thumb, it could be because I shut a drawer on my thumb, not because a hammer fell on it.

Nevertheless, I work.* Much of my work depends on thinking, leaving little in the way of a visible trail until some sort of product is finished. Writing curriculum is different from any other educational work I have ever done. There are no tests or papers to grade, no lectures to write, no lessons to develop, no students lined up at the door. Just a blank computer screen. It may be days before any sort of work product appears.

Starting with an idea about a project or a publication, I think about it, maybe read what someone else has written, and think some more. My fundamental question is always: “How do we make this idea (or subject or event) make sense and become meaningful to North Dakota’s young students?”

On the other hand, I might start out to tackle a project with no idea at all. Take, for instance, articles in the North Dakota Studies newsletter. There is no formula or master plan to determine the next topic. I look for areas that we have not covered thoroughly in other publications. Or, I think about what might be a topic of current interest. In the next two years, the nation will be marking the 100th anniversary of World War I. I expect to publish at least two articles about the role North Dakotans played in that war in North Dakota Studies newsletter. It will take a great deal of thinking to figure out how to write a historically accurate, student-friendly, and remarkably brief article on that big topic.

Another project on the horizon is the re-writing of Early Peoples of North Dakota by C. L. Dill. The thinking questions ahead of me involve how to make archaeology interesting and relevant to students and the general public. And how do I, trained in history, interpret archaeological evidence in a way that does no harm to either profession? That project will take a great deal of staring off into space, stretching back into my chair, and, the hardest work of all, making it look like work.

*Of course, I don’t work entirely alone. I get a lot of help from the Coordinator of North Dakota Studies, Neil Howe, and our techie-geekie, enormously talented new media specialist, Jess Rockeman. In addition, there are dozens of very knowledgeable people in every division who support the work of North Dakota Studies.