When I taught school, it was part of my first-day routine to ask my students if any of them liked history. The complete lack of raised hands taught me that there was no point in asking. I was working at a private boarding school with students from all over the country, and not even one of them liked history or was at least willing to admit it.

If you had asked me in high school, I would not have raised my hand either. I was in college when I discovered my love of history. What changed? The presentation.

When it comes to middle and high school history, there is an emphasis on rote memorization and the regurgitation of facts. I understand why. Teachers have a set of standards they are supposed to achieve and not a lot of time to reach them. To accomplish these goals, teachers must omit chunks of history like the entire Gilded Age. (According to state standards, nobody needs to know about the Gilded Age — unless you end up managing the Chateau de Mores.) The syllabus for my world history class included the impressive statement that we would cover 40,000 years of history in 36 weeks. This was like taking a 700-page book and adapting it to a 90-minute film. At best, you are only scratching the surface of the story.

History is a social science, or as I would tell my students, it is a skill set. It is about looking at sources and developing your interpretation about what happened. When you focus on the skills and the analysis rather than striving to check items off a list, then you can dive into the parts of history that are fascinating, mind-blowing, or odd. The elements of history that make the topic fun. If you have ever seen a student’s reaction to learning that England and Spain went to war over an ear, then you know what I mean.

State historic sites can have the same presentation problem. There is not enough time to cram in all the fascinating information that staff have spent countless hours researching into a short visit. Staff can suffer from a mindset that we have to tell you everything, or we are not doing our jobs. While lots of accurate information, facts, and stories will fascinate some visitors, for others, too much information is not a compelling experience.

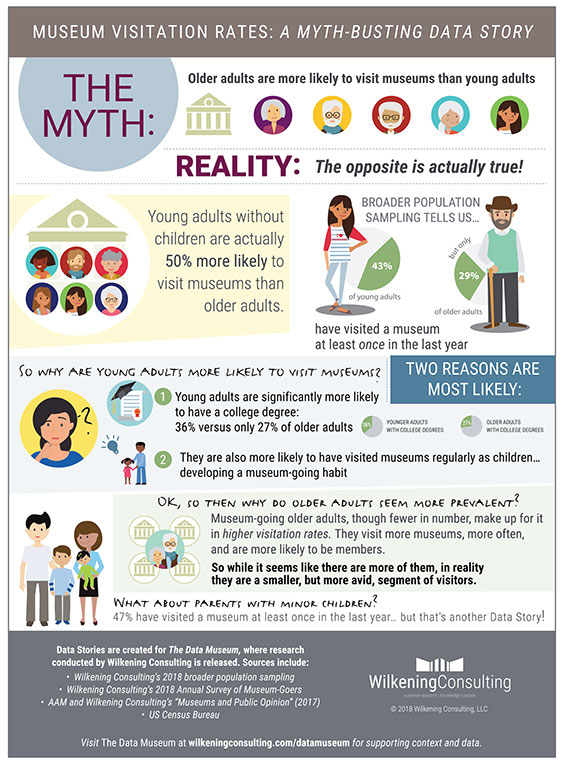

Who do you think is more likely to go to a museum, young adults or senior citizens? The answer seems obvious, and most would assume that museums are for the older generation and don’t fit the lifestyle of the tech-savvy younger generations. But according to a 2018 study conducted by Wilkening Consulting, young adults are 50 percent more likely to visit a museum than older adults.1 There are several reasons for this, but a leading reason is that they visited a museum or site as a kid and had a memorable experience.

Part of my job as state historic sites manager is trying to figure out what makes a memorable experience. It is a difficult task as there is no magic formula. There are a multitude of ways that people experience a site. From the moment a visitor pulls into a site, they are already experiencing it. Some issues are easy to address, such as making sure that the site is well maintained and that the staff is friendly and knowledgeable. The tricky part is when you try to take it to the next level. Our Hands-on History program is adding opportunities for visitors to touch, try, experiment, and play with historical items, clothes, and games. We are also looking at new technology such as augmented reality and smart speakers and how we can leverage that technology to create new and exciting ways to interact with our sites and exhibits.

And sometimes it is just about finding what makes a site cool. My nephew got to visit the Ronald Reagan Minuteman Missile State Historic Site with me as part of the 10th anniversary as a state historic site this summer. After getting to go 50 feet underground and seeing the art on the walls, he insisted on buying a t-shirt, and wore it almost every day he was at the family lake cabin and on the first day of school. Why? So that people would ask him about it, and he could share the story of his memorable experience.