I like to consider myself a historian specializing in textiles. I am in my element when I can talk to visitors about quilts or catalog a lovely dress. As curator of collections management here at the State Museum, I can also hold my own when it comes to talking about a variety of subjects from furniture to guns. Bugs are a whole different matter, however. While I have a background in science, the only thing I know about insects are which ones are dangerous to museum collections and the phone number for our pest control professional who can take care of them.

When we were offered and accepted a cabinet containing a collection of butterflies and moths, I was mildly concerned about cataloging them, but the opportunity to get a butterfly collection that represents the upper Midwest was too important to let those concerns get in the way. In the summer of 2021, I was able to find the perfect intern, a museum studies student with an interest in entomology. Mary Johnson, a graduate student at the Cooperstown Graduate Program at SUNY Oneonta, had exactly the background we needed to get the collection cataloged. Unfortunately, we could only fund the internship for 2 1/2 months, and there were well over 1,000 insects to identify and catalog! It was impossible for her to catalog the whole collection. (You can read about her project and others in this blog written by our interns last summer.) This meant someone would have to catalog the rest. But who? (Insert the sound of crickets chirping here. And no, they are not from the collection drawers!) As fate would have it, it fell on me—a history person, a textile person, and a quilter—to identify and catalog drawers full of butterflies and moths.

While butterflies are beautiful, they are way out of my sphere of knowledge. The butterflies I am used to working with look more like these and are embroidered with thread and yarn.

Close-up of quilts from the State Museum collection. SHSND 17662, 1981.93.1

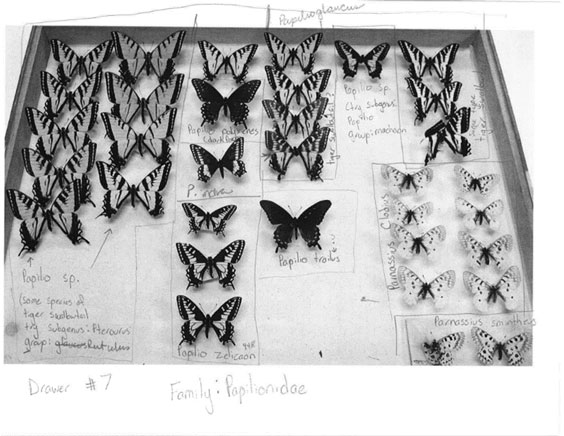

Still, I had a couple of things going for me. First, collectors house like specimens together so a drawer might be one genus and the various species in that genus will be lined up together. Even so, when faced with a drawer like the one below, it can be a bit daunting for someone without an entomology background.

SHSND 2021.10.434-.467

My second help was that Mary made a guide for each drawer. She photographed the drawer and labeled or at least narrowed down the possibilities of which species the various groups of butterflies belonged to.

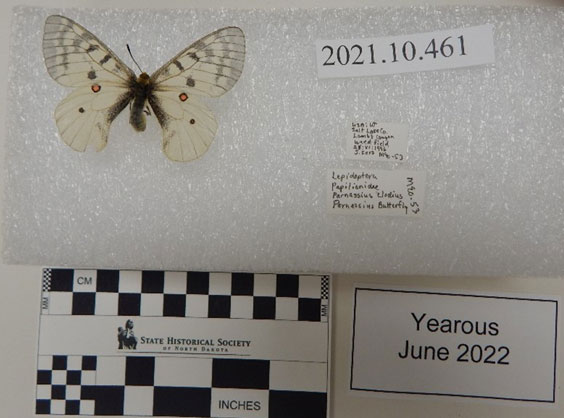

Lastly, some but not all of the specimens were identified by the collector. Some but not all also had collection locations identified, which helped when a species is found in a specific area.

Here is an example of a butterfly with full identifying information, including where and when it was found, its species, and who found it. SHSND 2021.10.461

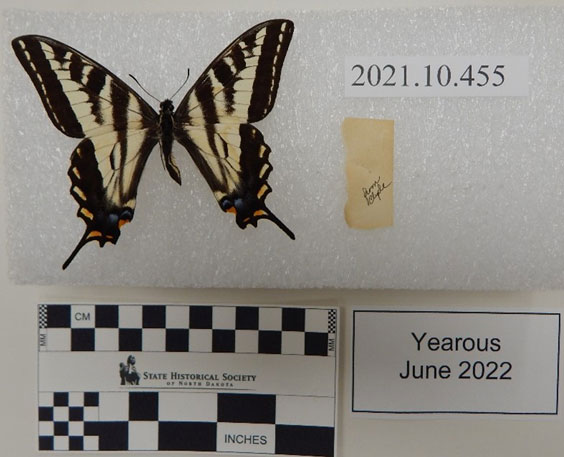

But many specimens had little or no information.

Sorry, folks, but the “From Clyde” tag doesn’t help me much. SHSND 2021.10.455

When I was lucky and a butterfly’s species was noted on a tag, I could safely assume the butterflies in the same column were also of that species. When identifications didn’t agree, I felt I needed to verify the species. I also knew that as research has evolved, species names have changed; animals once thought to be different species might now be combined in the same species, or animals thought to be the same species might be separated due to what my untrained eye sees as a minor variation. With many of these specimens collected and identified nearly 50 years ago, changes were a possibility.

But how was I going to verify the identification? I did what anybody else would do—I turned to the internet. In the past, internet searches have helped me with everything from how to tie a necktie to how to wear a Bohemian folk costume to the names for various parts of a saddle, and I was hoping it wouldn’t let me down when it came to identifying butterflies. I found many websites. Some were scientifically written and over my head; others were geared toward kids and way too simple. A few were written for folks like me using plain English with enough detail to help me identify different species. Even with the collector’s notes, Mary’s notes, and help from websites, trying to decide if a specimen was an eastern tiger swallowtail, a Canadian tiger swallowtail, or a western tiger swallowtail wasn’t easy.

“Other duties as assigned” is a broad category I never would I have thought would include butterfly identification. But the task turned out to be an interesting adventure for this historian and has given me a better appreciation for the work of all scientists.