Cattle Culture Stories Come Alive in Flashy Western Attire

Our upcoming exhibition Fashion & Function: North Dakota Style shoehorns 19 thematic sections into the 5,000-square-foot Governors Gallery of the State Museum. That is a lot of information and even more stories.

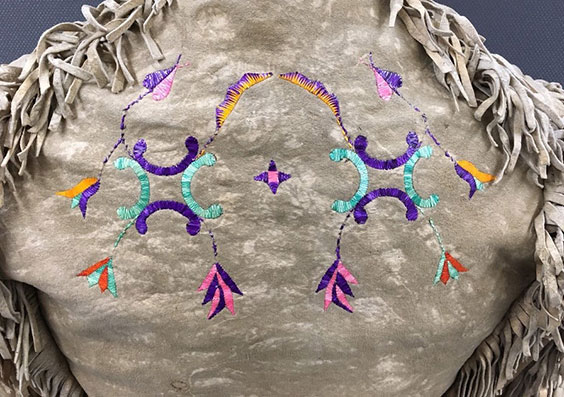

One such story involves a buckskin suit included in the Cattle Culture section of the exhibition. The suit—consisting of a matching fringed coat and pants—belonged to Franz Hanneburg, who worked on a ranch near Hebron. As is often the case with historic garments, we don’t know how he came to own the suit in the 1890s. We also don’t know the maker’s name, but it was probably a woman affiliated with the Sioux/Nakota/Yanktonai.

Front view of buckskin suit. SHSND 2018.5.1-.2

The suit represents a significant earlier element in Western history—the military scout. Beginning in the 1860s, military scouts adopted this hybrid combination of European-cut garments fabricated and embellished with regional materials—in this case, tanned buckskin and porcupine quills. It was a style first romanticized in The Leatherstocking Tales of James Fennimore Cooper and in the writings of Washington Irving, then later adopted by several scouts when they became theatrical performers and led the Wild West shows popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It is the flamboyant style favored by notables such as Buffalo Bill Cody, Wild Bill Hickok, and Pawnee Bill.

This flashy suit style wasn’t limited to showmen; we are also highlighting studio photographs of the Marquis de Morès and the photographer Frank Fiske in similar scout-inspired outfits in the exhibition. The Hanneburg suit is cut after a European-style lounge coat pattern using set-in sleeves and a distinctive diamond-shaped back panel and accented with patch pockets. The two pockets are die-cut buckskin—possibly using a u-shaped chisel—and possess a decorative reverse-flute edge.

Detail of back yoke.

Detail of patch pocket with fluted edge.

This windproof buckskin coat is fully lined with red wool, trade blanket fabric and would have been an effective buffer against the region’s brutal climate. The fringed coat is also embellished with a delicate pattern of stems and leaves worked in multicolored, dyed porcupine quills. Interestingly, a change in the decoration scheme is evident. As is the case in several locations on the coat, there are graphite, hand-drawn guidelines for flowers that were never executed.

Graphite pattern for quillwork.

The stylistic legacy of the Hanneburg suit is represented in another garment in the Cattle Culture section, an embroidered wool shirt from the 1950s. While the two garments are remarkably different, they share a common lineage in the evolution of Western fashion.

Embroidered black wool shirt. SHSND 2011.53.1

Up until the mid-19th century the prevailing mode in men’s fashions could rarely be called conservative or subdued. Men very often appeared as strutting peacocks, decked in rich, patterned fabrics, intricately cut tailoring, elaborate embroidery, and bright, flashy color combinations. The dandies of those times, the English Macaronis and the French Incroyables of the old regime, were swept away by the somber grays and blacks of the Industrial Age.

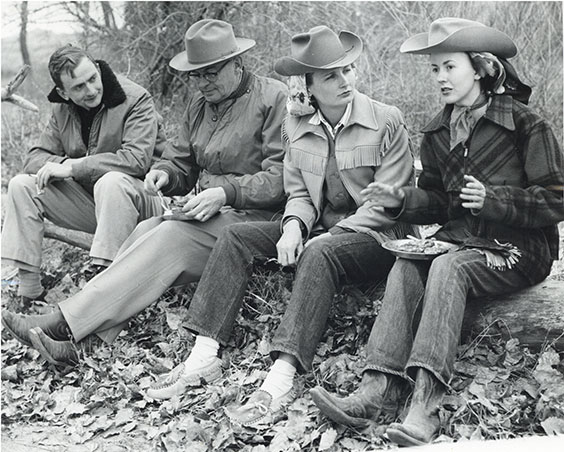

How curious that at the same time—and in the most unlikely of settings—the ostentatious plainsmen and scout suits of the American West took hold. The style found its way into the first generation of Western showmen and women, and easily transitioned to the silver screen in the early days of serial movies. Buckaroo stars such as Tom Mix and Tim McCoy provided macho swagger while draped in historic flamboyance.

Wild West shows, rodeos, and dude ranches perpetuated the look, and by the postwar America of the 1950s, the genre was firmly entrenched in popular culture. While masquerading as the most American of icons—the cowboy—no one would question or suspect an old-world dandy preference for bright colors and intricate embroidery.

While our black wool cowboy shirt is fairly subdued, its contrasting white rayon chainstitch embroidery clearly reflects the legacy of the quillwork on the Hanneburg suit, right down to the especially elaborate flourish across the back yoke.

Detail of back yoke.

Join us in early 2021 to experience these two fine examples from the holdings of the State Historical Society of North Dakota—along with many more—when we premiere Fashion & Function: North Dakota Style.