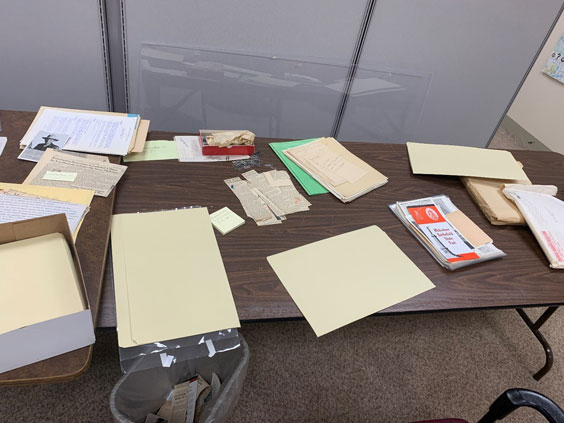

October is American Archives Month, which highlights the work archivists do as well as the collections, stories, and history we share with the public. I thought we’d kick off our celebrations in the State Archives with a discussion of the best (or worst) archival-themed scenes in film and TV. After all, archivists love seeing archives, records, and old books used in our favorite media, but some depictions better represent us and our work than others. I asked staff what their favorite or least favorite archives-related movie or TV show scene was and why, and here are their top answers:

Anne Loos, Audiovisual Archivist

In “Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones,” Jedi knight Obi-Wan Kenobi visits the Jedi Archives, where the chief librarian, Jocasta Nu, helps him search for information about the planet Kamino. When no record of Kamino can be found, Obi-Wan says to Jocasta, “Impossible. Perhaps the archives are incomplete.” She tersely responds, “If an item does not appear in our records, it does not exist.” The “Star Wars” canon later establishes that Jedi-turned-Sith Count Dooku erased the record about Kamino from the Jedi Archives. As much as I want to believe that the Jedi Archives is infallible, this certainly raises questions about the vulnerability of its records to internal and external tampering. That said, if Obi-Wan had not reacted in a manner that would offend any library/archives professional and instead kindly pointed out that the gravitational pull indicated there was in fact a planet there, then perhaps Jocasta would have continued to work with him to get to the bottom of the missing planetary record.

Larissa Harrison, Government Records Archivist

“The Mummy,” starring Brendan Fraser and Rachel Weisz, came out in 1999 while I was finishing grad school classes in public history. It gave me and my fellow students an inspiring character in the figure of Evelyn Carnahan, a female librarian who is active in the adventure, not simply sequestered in the library. Yes, she is more an Egyptologist and archaeologist than your typical reference librarian. However, she uses her library knowledge to defeat the Mummy and go on more adventures. If Dr. Henry Walton “Indiana” Jones Jr. can spend more time in the field than the classroom, then Evelyn can leave the library and still be proud of where she gained her knowledge. The film also represents one of the few times a librarian is not depicted on the silver screen as a meek and mild woman in need of breaking out of her shell. Evelyn has a goal independent from the men in her life, and she goes after it, making her own decisions on her own terms.

Emily Kubischta, Manuscript Archivist

One of my favorite archives scenes is from the movie “The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring.” Led by torchlight, wizard Gandalf the Grey visits a room filled with ancient scrolls, stacked books, and dusty documents to determine whether he remembers accurately the story of the One Ring of power. Teacup in hand, pipe in mouth, Gandalf reads the millennia-old account of Isildur, High King of Gondor, which tells of the discovery of the ring and notes the text (in the language of Mordor) that appears on the ring when it is submerged in fire. Gandalf uses that information to determine whether Bilbo Baggins’ magic ring truly is the “one ring to rule them all” under Sauron’s evil power. This knowledge drives the fate of everyone in the story as well as the future of Middle Earth.

Although smoking and tea drinking are no longer allowed in archives, I like this depiction of archives and libraries as places to retrieve common knowledge and information that has fallen out of use, providing a final, authoritative answer to a variety of life’s important questions. Although modern archivists store their materials according to professional standards to protect them from dust, cobwebs, light, and other deteriorating environmental factors, the system at Middle Earth’s archives apparently preserved the documents in their care for thousands of years, rendering them usable and useful when needed. Furthermore, a helpful archivist was there to show Gandalf the collection and guide his search, just as our reference staff are available for researchers at the State Archives.

Sarah Walker, Head of Reference Services

I’m sure we all enjoy seeing our profession reach a wider audience through television and movies, but I also think these depictions serve a useful, popular culture link to some of our lesser-known materials, such as microform. While I still consider the scene that allows me to reference microform in “Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull” to be one of its very few redeeming features (sorry!), there are a surprising number of other film references to this medium. A favorite of mine is “WarGames,” starring young Matthew Broderick and Ally Sheedy. I watched it for the first time after I had started working at the State Historical Society of North Dakota, and while I found it enjoyable, I have to admit that aside from its anti-war message, the main thing I remember about this ‘80s-tastic movie was that Broderick’s character uses microfilm. Let me just add that I literally cried out in excitement when I realized he was using a microfilm reader like the ones we once had here in the Archives.

Megan Steele, Local Government Records Archivist

In “Desk Set” (1957), Katharine Hepburn plays Bunny Watson, the head reference librarian for the Federal Broadcasting Network in Manhattan. Bunny is an amazing source of knowledge gained largely from her years working in reference. But when Richard Sumner (Spencer Tracy) is called in to install his invention EMERAC (Electromagnetic MEmory and Research Arithmetical Calculator), staff fear this “electric brain” is meant to replace them. This movie is great at covering some of the quirks of working reference, mainly the flood of questions from the serious to the supremely random that staff encounter. For me this movie shows that computers are good assistants, but nothing beats institutional knowledge within the information field.

Joy Pitts, Photo Archivist

The Vatican archives scenes in the movie “Angels & Demons” show viewers an impenetrable fortress of knowledge. But real-life archives (and probably even those of the Vatican) do not have the resources to create a completely hermetically sealed, oxygen-fueled system of rooms to house archival materials. In the movie Robert Langdon (Tom Hanks) searches the Vatican archives for clues to an Illuminati plot to take over the Catholic Church. In one scene, Langdon enters one of the archival rooms with a member of the Swiss Guard, and after a short period of time, an unidentified person shuts off the oxygen to the room. To escape, Langdon must not only knock over a huge shelving unit but also shoot at bulletproof glass. While it would be best practice to keep all materials in an anaerobic environment, only important materials/collections would ever be stored in such a manner. (Due to the slow pace of deterioration by exposure to environmental factors—apart from light, light is very bad—not all materials are important enough to justify the costs associated with the building and upkeep of such a system.) I have seen a hermetically sealed system at the National Archives for the Declaration of Independence and other foundational documents, but these were sealed cases not entire rooms. So please don’t think most archives have a system of these rooms that we hide from the public—that’s just silly.

Daniel Sauerwein, Reference Specialist

There are a couple fun references to the use of archives or research collections in episodes of “The Simpsons.” One of my favorites is the season seven episode “Lisa the Iconoclast,” where Lisa Simpson visits the Springfield Historical Society to do research for a school paper on the town’s founder, only to find a document that reveals his darker side. Her research garners pushback from the town’s residents, but her findings are proved correct. This episode conjures up the issues sometimes faced by archivists and historians when dealing with materials that challenge long-held beliefs and interpretations about a particular location’s past. Another example is from the season six episode “Sideshow Bob Roberts,” when the character Sideshow Bob wins the mayoral election. In the episode, Bart and Lisa investigate Bob’s win and in the process visit the Springfield Hall of Records, where they view the voter rolls for the election and discover fraud. These episodes provide examples of how archival materials may be used to gain knowledge and enact change.