You have what? Unusual Artifacts from the Collection of the State Historical Society

A mission is an important thing for a museum. It provides a focus and a compass for how we interact with the public, what we put in our exhibits, and what we collect. It defines what we do and gives us a purpose for why we do it. Largely an invention of the 1960s and 1970s, missions emerged in museums at a time when the US bicentennial stoked a great deal of interest in history and the field became more evenly professionalized. Our mission is as follows:

To identify, preserve, interpret, and promote the heritage of North Dakota and its people.

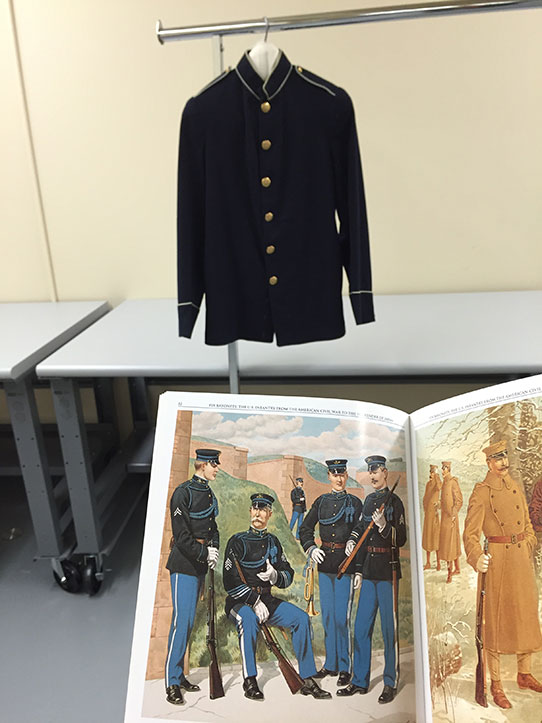

Without that focus, many museums of the early 20th century functioned as a “cabinet of curiosities” of sorts. They often displayed items that visitors wouldn’t normally see in everyday life, sometimes peppered in amongst artifacts more familiar to the viewer. They showcased items from foreign lands, often picked up as souvenirs during travel, or at times, highlighted the unusual and bizarre.

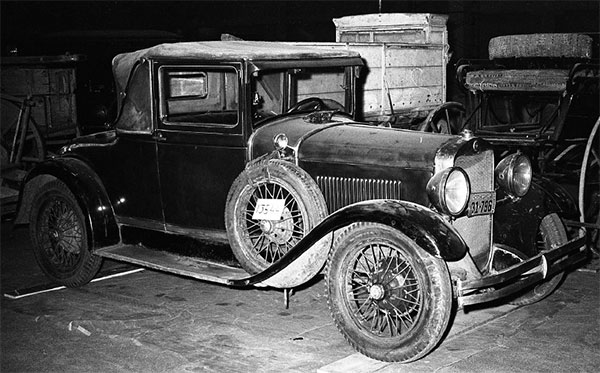

The Liberty Memorial Building on the capitol grounds housed the State Museum from 1924 until the current Heritage Center was completed in 1981. Here you can see one of the displays, which contains covered wagons and steamships, forms of transportation not unusual for North Dakota, juxtaposed with a model of a Spanish galleon and other foreign ships.

This isn’t intended as criticism of the past. What we collected says a great deal about what we valued as a society and speaks to the curiosity that is inherent in human nature. In a time before the internet and trans-Atlantic flight, a visit to the museum was a way that you could physically see pieces of a faraway land or event that may otherwise have been inaccessible. And really, that is one of the ways we still serve the public today.

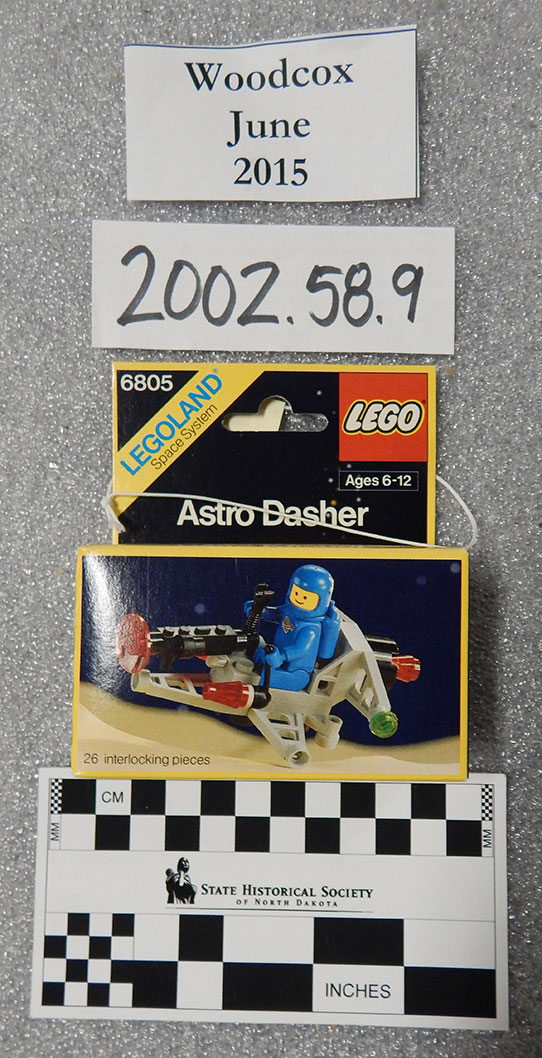

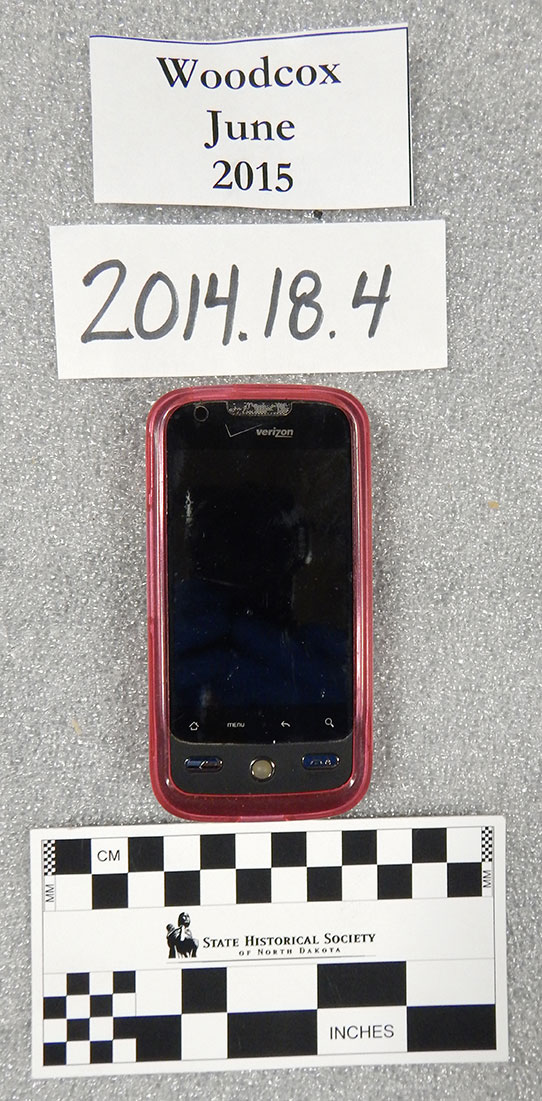

While the State Historical Society has generally focused its collecting on North Dakota, we still have some artifacts that were collected long ago that are very random. I’d like to highlight some of those items for you. Once the process is complete, an artifact has enough information recorded so that it and its story are easily accessible to staff, visitors, and researchers.

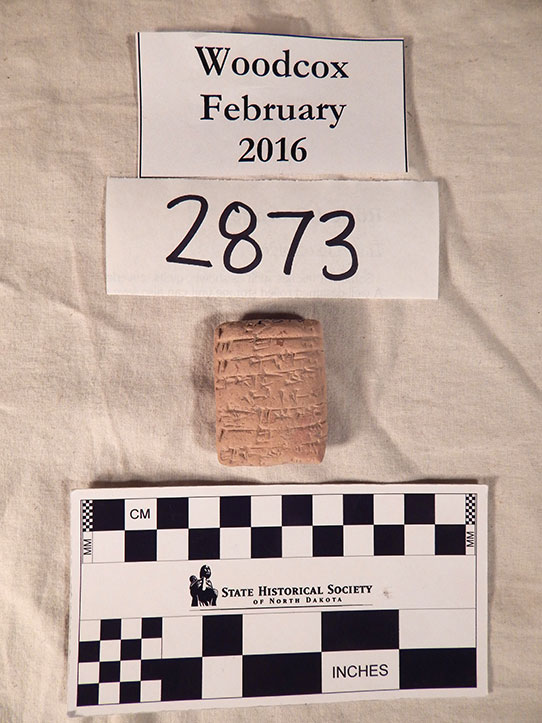

The Historical Society holds a set of Babylonian cuneiform tablets dated to 2350 BC. This tablet was acquired in June 1924 and is reportedly, “A list of cattle and sheep delivered to a shepherd for herding. Found at Drehem [Iraq], a suburb of Nippur where there was a receiving station for the temple of Bel.” While having no connection to North Dakota history, it was collected to allow people to see a piece of ancient civilization that they might otherwise only read about.

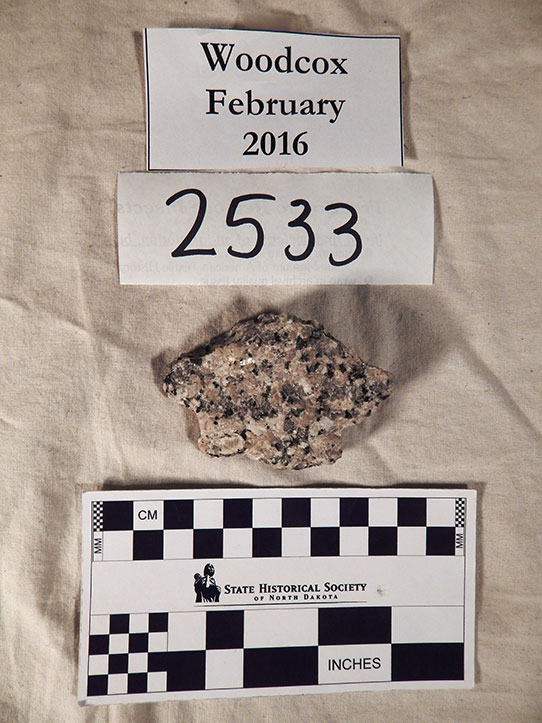

This is a chunk of granite taken from the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C., when one of the bricks was replaced with stone from North Dakota. On the surface, it is just a rock. If you saw it in your driveway, would you attribute any significance to it? Instead, it is imbued with significance due to the location it came from.

Known as the deer locked in death, these unfortunate deer were found impaled by their antlers near Belfield, North Dakota. They were mounted and displayed at the North Dakota exhibit at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, in 1901. Definitely an example of the bizarre, they could also be seen at the Liberty Memorial Building for many years.

Seeing these items makes me think about what we value today and how our views have shifted in the century since the Historical Society first began collecting. What are your valued possessions? What do they say about you?