Collecting the Everyday: The Most Important Thing You Probably Don’t Know We Do

When you think of a museum collection, what types of artifacts do you think of? Maybe dinosaur bones, antique cars, or a World War II uniform? Something old, maybe even ancient. While collecting from the past is an essential part of the Museum Division’s function, what is just as important is collecting from the present.

Most people don’t know that we actively collect from today’s world, and the typical reaction when they find out is, “Why would you want that?” To many, modern items often seem too insignificant to belong in a museum. However, the purpose of the Museum Division’s collection is to preserve a three-dimensional historical record of life in North Dakota. What do these everyday items say about our values, our technology, and our society? What common stories are captured and preserved from our lives? What will they tell researchers about us in 100 years? 1,000? After all, what is now old and distinctive was once a part of everyday life.

Take a look at five artifacts that we have collected from our contemporary world. Do you have anything from your life that can add to North Dakota’s story?

1. Car Seat (2016.43.1)

Used by the donor for nine months of 2015, the car seat was a hand-me-down from a friend whose son had grown out of it. Some distinctive things about the artifact include an expiration date, which is a relatively new safety feature. We also know that the print on the seat cover is called Cow-Moo-Flage, which amuses me to no end. Would we have captured those stories had we collected the item 100 years from now? We likely would not have, and it adds a human dimension to the artifact. The advances in technology also say something to me about how much we, as a society, value our kids!

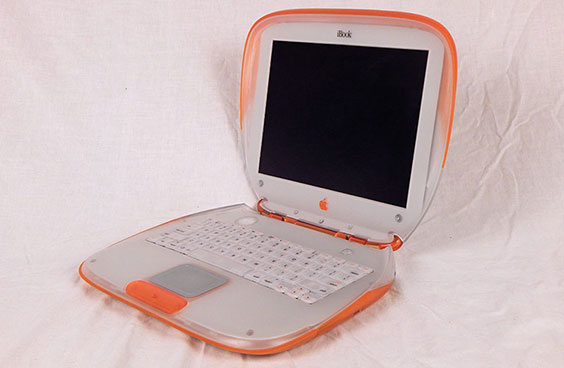

2. Apple iBook G3 Laptop (2016.22.1)

Like many of our more recent artifacts, the laptop came from our State Historical Society staff. It was purchased through a grant in 1999 for $1,599 (nearly $2,500 in 2018 dollars) so the agency could build a website to “take advantage of the public’s growing use of the internet.” Sporting 64 MB of ram and a 6 GB hard drive, its specifications make it practically unusable by today’s standards. It not only demonstrates the advances computers continue to make, but with its distinctive exterior, shows late 1990s fashion. It also documents efforts to adapt to a major shift in society: the proliferation and use of the Internet.

3. Cereal Box (1985.46.4)

We have a large collection of food containers. It’s something that typically gets thrown out or recycled, so why would a museum want it? How much of our time and money do we spend either preparing or purchasing food? And do you really understand a culture if you don’t understand how and what they eat? This cereal was purchased for the donor’s young children in 1985. How many of us as kids spent a Saturday morning eating a bowl of cereal while watching cartoons? It’s a common childhood story that is captured when we preserve this artifact.

4. Samsung Galaxy S4 Smartphone (2016.41.1)

How can you talk about 21st century life without acknowledging the monumental shift brought about by smartphones? We have mobile phones in the collection running as far back as a 1980s car phone. In addition to the stories collected with each donation, each reflects changing technologies and the transition to the all-purpose devices we carry around today.

5. Selfie Stick (number not yet assigned)

Part of the rise of smartphones is all the accessories that come along with them. Though selfie sticks have been around in one form or another for decades, they became a popular smartphone accessory within the last few years.

Do you have something from your life that would add to North Dakota’s story? Send in a potential donation questionnaire on our website.