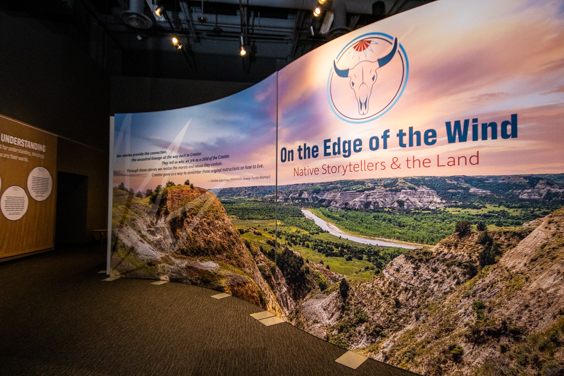

King Spud: When North Dakota’s Baked Potato Day Stormed the 1915 World’s Fair

A crowd gathers at the North Dakota Building for Baked Potato Day, April 27,1915. A sign on the building invites people to “Have A Baked Potato On Us.” SHSND SA E0948-00001

It was a “potato stunt” for the ages.

In 1915, the town of Larimore in Grand Forks County shipped thousands of their prized tubers, each weighing more than a pound, to the Panama-Pacific International Exposition (aka the world’s fair) in San Francisco.

Fairgoers flocked to Baked Potato Day that April 27 at the North Dakota Building, where two large ovens had been set up outside to churn out hot buttered spuds, cooked up by a Great Northern Railway chef and served by “pretty girls.” Mollie Larimore, widow of the town’s namesake, N.G. Larimore, was in attendance for the festivities along with other dignitaries. Souvenir plates, spoons, and buttons were distributed to the assembled, who were entertained with lectures, tater races, and a Native American potato dance.

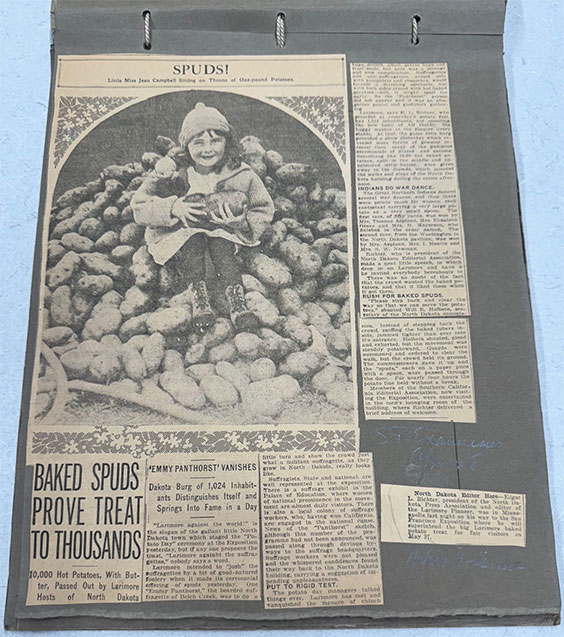

Larimore spuds head to the World’s Fair, 1915. OCLC 8002312

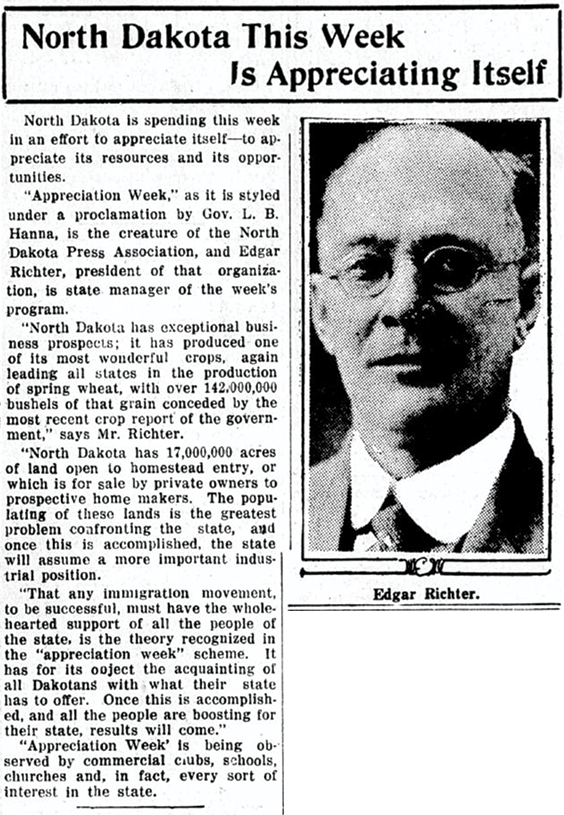

Heralded as a “big ad for the state” by newspapers, Baked Potato Day was hatched by none other than Larimore Pioneer editor Edgar L. Richter, president of the state’s press association and an energetic North Dakota booster. A local subscription drive raised $230 to send the spuds to San Francisco from Larimore, said to be home to the world’s largest potato warehouse at the time. This was hardly tiny Larimore’s first turn in the world’s fair limelight. In 1893, foreign commissioners from the Chicago World’s Fair visited the Elk Valley Farm, a bonanza farm founded by N.G. Larimore, which attracted international attention.

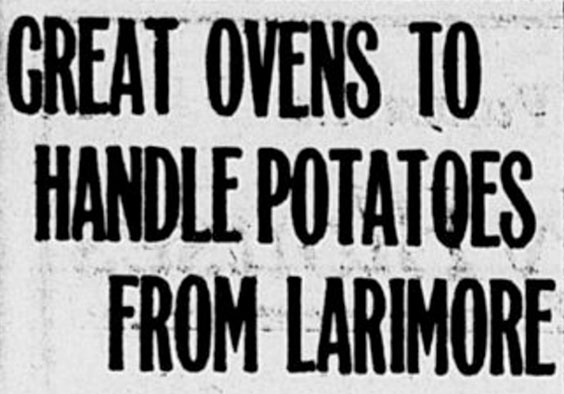

Grand Forks Daily Herald, April 23, 1915, p. 7

Baked Potato Day was not without some controversy, however. In an unusual twist, a humorous talk by anti-suffragette “Emmy Panthorst” was pulled by program organizers fearing retribution from suffragists and the prospect of a messy brawl involving combatants “armed with hot baked potatoes.” Curiously, news reports at the time insinuated that the mysterious Panthorst, who failed to appear, had been none other than Richter himself.

The State Archives houses a scrapbook of clippings from Baked Potato Day as well as other items related to the 1915 World’s Fair, including photographs, souvenir books, and the North Dakota Building’s visitor register. SHSND SA 30152

This minor hiccup aside, the day came off without a hitch, and Richter returned home pledging to turn Larimore into a winter resort for New York millionaires. Newspapers carried reports of increased California demand for North Dakota tubers. The “baked potato king” or “Spuds,” as Richter was called, would go on to spearhead North Dakota Appreciation Week, another successful booster event, that November. “Probably no man in the entire state of North Dakota,” the Fargo Forum and Daily Republican declared, “has done more to spread the gospel of the glory of the commonwealth throughout the nation.”

Jamestown Weekly Alert, May 6, 1916, p. 5

While North Dakota did not become known as the Potato State as some papers predicted at the time, 110 years from that momentous day, the spud remains an agricultural staple. North Dakota ranks fifth in the nation in potato production, and an endowed professorship of potato breeding was recently established at NDSU. The potato crop is one of many contributing to North Dakota’s agricultural dominance, which will be highlighted as part of an exhibit State Historical Society staff is working on to mark the nation’s upcoming 250th birthday.

Grand Forks Daily Herald, May 7, 1915, p. 10

As for Richter, his post-potato days were eclectic to say the least. A vocal opponent of the progressive Nonpartisan League, Richter launched an unsuccessful bid for state Senate the following year. He also served as president of the Larimore fire department, helped found a moving and construction company, worked as an insurance agent and auto licensing inspector, and was elected Fargo justice of the peace. During World War I, he traveled North Dakota organizing the “Four Minute Men,” who gave speeches to rally support for the war effort.

Richter ended his career as deputy state pool hall inspector, dying in 1926 at age 64. Regrettably, the Bismarck Tribune obituary failed to mention his Baked Potato Day antics at all.