Sometimes the best way to understand a fossil is to go fishing. A number of our paleontological sites across North Dakota have fossil bones from the family Lepisosteidae (gar or garpike) preserved. While gar are still alive today, their range tends to be more southern and eastern, closer to warmer, slow-moving waters and bayous. While the living gar may not be an exact match to our fossil gar, studying the bones from the living animals can help us better understand what we’re finding in the rock.

Our paleontology department has a small comparative collection of recent animals - things that may share similarities to fossil creatures we find. For instance, a modern deer may have similar bone structures to 30 million- year-old deer. A modern crocodile may have ribs and vertebrae that look similar to crocodiles that once roamed North Dakota 60 million years ago. The same goes for the gar.

This is where taxidermy comes into play. Instead of stuffing the skins of animals, we only keep the bones (similar to a European mount). To remove the flesh from the bones, dermestid beetles work wonderfully, but tend to smell, and can have the occasional bug escape artist. We can’t risk that in a museum. Burying the bones in the ground and letting nature do all the work is also an option, but that takes a bit of time and also needs a location to bury the critter. So we stick to simmering the bones in a pot.

For mammal skulls, this is a piece of cake. All the bones of the skull are knit together by sutures – think a bone zipper – and tend to stay all locked in place. Fish skulls, including our lovely gar, have very smooth joints between the bones (called synarthroses) that in life do not move much. However once the skin and connective tissue begins to break down, the skull bones will fall apart.

Since the fossil bones we find are all disarticulated (no longer connected to one another), we need individual bones from modern fish – not a completely intact skull. What we had to do here was make sure the bones fell apart IN ORDER while cleaning them. We simmer them for a while, gently scrub, and then pull off a single bone. Repeat. The bones were placed in order off to the side to dry, where they will be ready to eventually photograph or draw for comparison.

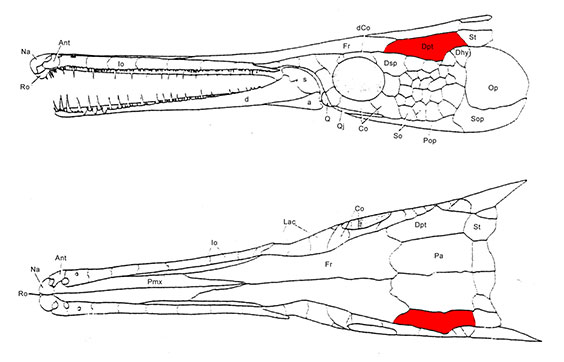

Here we have an articulated skull with the dermopterotic bone highlighted in red. This lets us know where exactly in the skull the bone is.

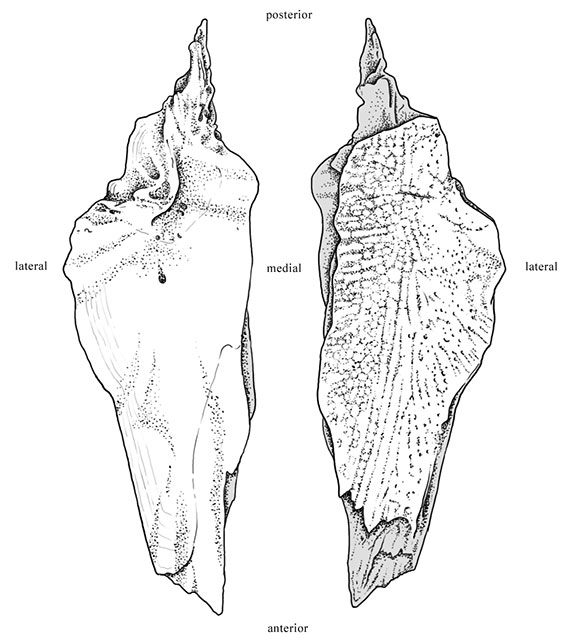

Next, we have an illustrated dermopterotic, from our recent gar stew. This helps us identify a single bone, if we ever come across a similar looking piece in the field.