Left: Expansion phase pictured here is of the Treehouse children’s exhibit, now fully finished and ready to go. Each phase seemed like a new gift to unwrap. (Photo by Brian Austin)

Right: This photo is of my supervisor and me at the Legislative Reception, where we were allowed into the construction areas. I had to wear a hard hat and a vest. Other staff here (Becky Barnes) decorated my hard hat so I could feel more myself.

When the State Historical Society’s expansion occurred, a lot of planning went into the exhibits that would populate the new and existing spaces. While I was uninvolved with that process in my role here, I really was eager to see what would be used. Staff who were not part of the installation process were not given ready access to the areas (understandably, or they may have had a few of us—okay, me—underfoot). So whenever we were given permission to sneak over and watch construction going on, or see a hint of what was going to be installed, it was exciting.

But I admit, as excited as I was for everything else, I really was looking to see what audio resources might be used from the State Archives.

I’ve talked about audio and video resources several times before; I wrote about conducting oral history interviews in my second blog post, and discussed the idea of transcripts of these interviews (or lack thereof), in my third blog post. I often group audio and video resources together, because there are some similarities between the two, and because they do go together in many ways. However, I primarily work with the audio files of these types of collections.While both are very important, the audio files are a little more dear to my heart.

We have various types of audio formats housed at the State Historical Society. Reel-to-reel, audio cassettes, microcassettes, records, and CDs are typical items in our collections. We also have some files that are formed or created as digital files. Just as is the case with any other collection, all of these must be stored specifically and properly in cooler conditions, and monitored for breakdown of materials.

Unlike some other items, however, the intrinsic historic value of the item has little to do with the structure of the format (which does admittedly still provide us with history and a timeline, showing the technology at the time). The value comes from accessing what is on the cassette, or record, or CD. Which means, we really need to find ways to preserve it so we can continue to use it.

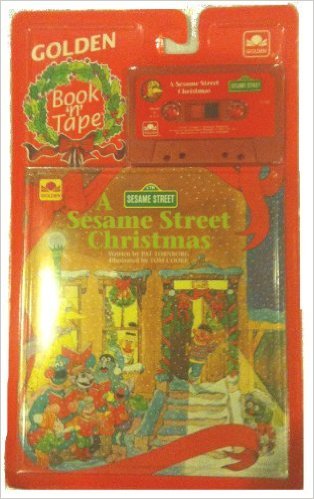

This is the elusive book-on-tape set I listened to so frequently when I was a young girl.

When I was a very little girl, cassettes were all the rage. (It was the 1980s and 1990s, after all.) I loved listening to all sorts of things, including music, and books on tape. I had one book on tape (A Sesame Street Christmas) that I listened to so many times, I wore the tape out. My mother actually purchased several more copies for me, because I kept wearing them out. I had other cassettes that I listened to so frequently that the tape pulled off of the reels, or wrinkled, or just jammed up in the tape player.

Obviously, the act of playing something so you can listen to it can cause wear or damage. But historic interviews and moments captured in time—those can’t be repurchased or reproduced. People want to interact with their past, and as archivists, we also want people to interact with their past. If we have an item here, we want to keep it here for the future—but we also want you to be able to hear the voice of your great-grandmother who settled in Minto in 1900.

Since around 2009, I have been increasingly working with these various audio components, transferring them to digital audio files. We did these only on request before I began working with these collections, and we did not store the files, or even have procedures set to name the files. In the years since, I have learned a ton about how to work with these formats.

Today, I have a set-up that allows me to plug different types of audio equipment into my computers and run the content through the software we use, the free program Audacity, transferring old audio to the very new digital formats. I save each file as an MP3, which is more compressed and easily accessed, as well as WAV, which is a more standardized, uncompressed file.

Fast forward to the opening of the exhibits of the State Historical Society’s expanded museum.

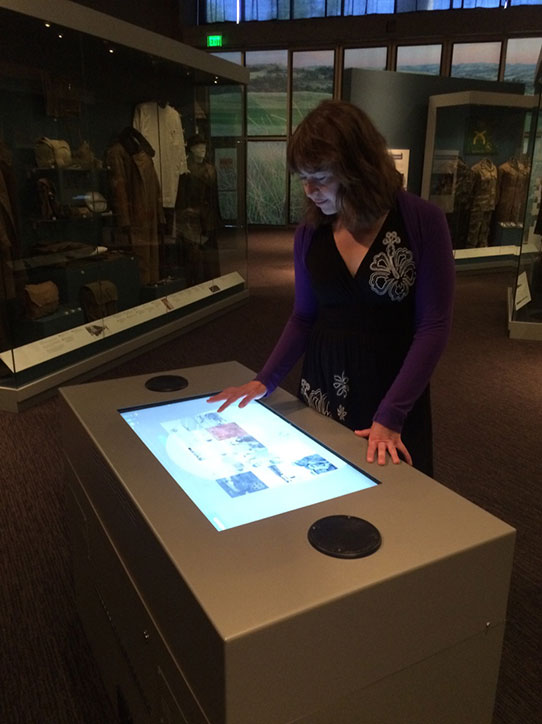

This touchscreen hub is located in the museum galleries and has a plethora of veterans’ histories on it.

Our museum space is a treasure trove of items from all across the agency. I am pleased to say that both video and audio files from the Archives did appear in the exhibits, along with maps, photos, and other documents. But nothing quite made me feel the same as when I found one of the hubs that had on it, among other things, oral interviews of a few veterans that I had both interviewed and digitized.

Occasionally, I hear other bits of interviews that I have digitized, or recognize names from interviews I have worked with. Some of them are from interviews I have done myself, but many more are ones that I simply worked with years after the fact. For me, it has become a point of personal pride. You start to become protective of these files. You want to make them their best and help them find their way into the world. You have made these items ready for the future. It’s the coolest thing.