If you were to look at a map of the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation with Arikara elders living in White Shield (North Dakota) today, they would tell you where they used to live. They would point to where their houses were, their relatives’ houses, their school, and the berry patches they walked to with their grandmothers. They would point to the churches, roads, and cemeteries, and the gardens they had to weed in the morning before they could play with their friends. They would describe these in astonishing detail. And this would be all the more astonishing because they would be pointing to the middle of the nearly 200-mile-long Lake Sakakawea. Nishu, the home they describe, has been under water since 1954.

Even, even to this day, if I jump in a boat, and I take that boat out on the lake, invariably I will go downriver. Go down the lake. Pretty soon I’ll be circling around and telling my grandkids or my kids, “I used to live right under this water right here.” (Almit Breuer, former Nishu resident)

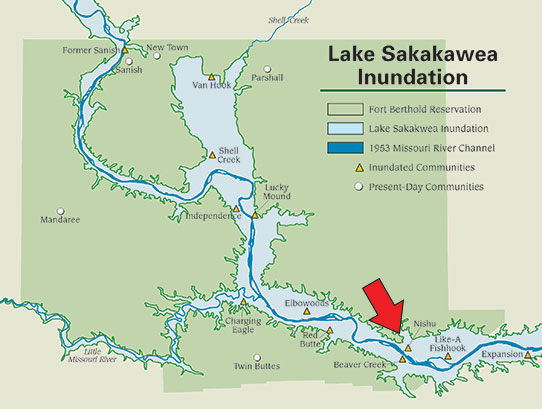

Map of Fort Berthold communities inundated by the Garrison Reservoir, showing previous river channel and current lake boundaries. (SHSND AHP Files)

Nishu was a 20th-century settlement on the Missouri River, established by the Arikara in the 1890s. It marked an important chapter in Arikara history, in which this Native nation simultaneously grappled with the effects of the U.S. government’s assimilation policies and maintained many ancestral traditions, such as corn agriculture. In the 1950s, they watched as the place they had made their home was slowly swallowed by the newly constructed Garrison Reservoir. Although it is no longer accessible, it continues to be a significant heritage place for Arikara people today.

Project participant and former Nishu resident Mary Bateman (W. Murray)

Very little information about Nishu exists in the written record. Furthermore, the people who remember living there are in their 70s, 80s, and 90s. This created a sense of urgency about documenting Nishu before people’s memories and experiences of it were gone forever. Younger generations have no visual cues for remembering Nishu, because they have only known that area to be a lake. This creates a serious disconnect between generations who have experienced the landscape in completely different ways. Since preserving the physical remnants of this place was not possible, we sought to preserve its intangible history – the memories, knowledge, and experiences of the people who knew it best.

Arikara elders Jerry White, Sr., Rodney Howling Wolf, and Duane Fox look at a map of Nishu. (W. Murray)

In 2014, the State Historical Society collaborated with the Arikara Cultural Center (ACC) in White Shield to conduct an oral history project. The goals were multifold, but the priority was to create a local archive of Nishu memories to benefit the contemporary Arikara community. Namely, we wanted younger generations to have a way to access this chapter of their past in the absence of physical reminders on the landscape. We are grateful to Dorreen Yellow Bird, elder liaison for the Arikara, for her support as she helped us connect with people who used to live in Nishu and the neighboring Elbowoods (also underwater).

Interviewing Joyce Nolan, former Nishu resident. (W. Murray)

Over several months, Dr. Brad Kroupa (ACC) and I interviewed 15 people, most of whom lived in Nishu. Some were either familiar with Nishu or had relatives who had told them stories about Nishu. Thus far, we have collected more than 30 hours of video and audio footage describing life in Nishu. Interviews recount everything from the central role of horses in transportation to the persistence of traditional kinship roles to what it was like receiving initial news about the Garrison Dam development that would destroy their homes. For example, we learned exactly how much kids dreaded having to help their parents weed the garden, the specific ways Arikara women prepared corn, whose father had a beautiful singing voice, the significance of military service in Arikara ceremony, the Nishu school bus route, who accidentally set their grandparents’ barn on fire, whose relatives had knowledge of healing, and what aspects of Nishu life people miss most today (and much more).

What we heard most strongly is that Nishu residents took care of one another. Despite the considerable distance between houses (owing to allotment policy), people visited one another often and unannounced, shared in subsistence labors such as gardening and cattle raising, and were connected by a strong sense of familial responsibility. People’s nostalgia about Nishu was tied to feelings of interdependence and support. Listen to this audio clip from our interview with Magdalen Yellow Bird, talking about the importance of visiting in Nishu.

Arikara Congregational Church in Nishu. SHSND Archives 0041-0260.

Understanding the Nishu experience casts new light on how traumatic the Garrison Dam was for Fort Berthold residents. The Garrison Reservoir split the reservation into five segments. Short visits to relatives on horseback became burdensome, hours-long car rides. The flooding of the most fertile agricultural land meant that corn agriculture–central to Arikara lifeways and identity for centuries– was no longer possible. The relocation also forced the Arikara into participating more fully in a cash economy, which prioritized self-sufficiency and individual property ownership. This undermined the communal aspects of their subsistence traditions and contributed to the partial erosion of the familial connections and obligations that had served to foster a sense of community in Nishu.

Mrs. Sitting Bear (Arikara) gathering corn (date unknown). SHSND Archives 10190-00791.

The Arikara Cultural Center is now using what was learned in the Remembering Nishu project to start community-building and wellness initiatives in White Shield, including the development of a community garden and youth research projects. In a few months these transcripts, audio, and video files will be available for you to review in full at the State Historical Society in Bismarck and the ACC in White Shield. In them, you will discover Nishu’s vital role in Arikara history and find insights into the human experience that extend beyond North Dakota. Through Nishu we understand the complex impacts of landscape loss and the role of tradition in creating healthy communities.

We are grateful to all project participants for being so generous with their time and knowledge, for their commitment to the preservation of Arikara heritage, and their profound concern for the well-being of future generations.