Five of My Favorite Things about the Collections Right Now

Since 2011, I have had the immense privilege of managing the State Historical Society of North Dakota’s archaeological collections, perhaps one of the most spectacular archaeological collections in the Plains. But as you are reading this, I am on the verge of a major cross-country move, and am suddenly cognizant of everything I will not have a chance to talk about in future blogs. Here are five random and cool things I have been thinking about or working on recently!

1) My Favorite Squash Knife

Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara women were gardeners. But “gardeners” does not quite capture the scale of their agricultural achievements, the significance of their efforts to the economic success of their communities, or the physical and intellectual work that went into growing corn, beans, squash, and sunflowers this far north. Families would have plots ranging from 3-5 acres, so that for any village, the “gardens” might cover several hundred acres.

The squashes grown by the three tribes were typically harvested in the fall. They were sliced with squash knives into rings to be hung and dried for winter. Squash knives are flat, thin cutting tools made from animal bone. Typically, squash knives were made from bison scapulae (shoulder blades), because the scapula is one of the only bones in a bison’s skeleton large and flat enough for the job. The edge would have been ground to a sharp edge to cut through all those squashes after the harvest.

Last year, one of our volunteers was rehousing an older collection into archival materials, and she came across a squash knife. It was cool, but not uncommon. But then someone noticed that the knife had a cranial suture going down one side! That is because the scapula is not the only flat section of a bison’s skeleton. The top of the cranium (skull) is also flat, and was occasionally used to make squash knives as well. This was by far my favorite find of the last year.

This is a squash knife made from a bison cranium. Notice the cranial suture (here it looks like a black wavy line) extending from the left margin toward the upper right.

Here is a picture of the squash knife superimposed on a bison cranium, so you can see what part of the bison was used to make it. (Image courtesy Meagan Schoenfelder).

2. My Favorite Solutions for Artifact Storage

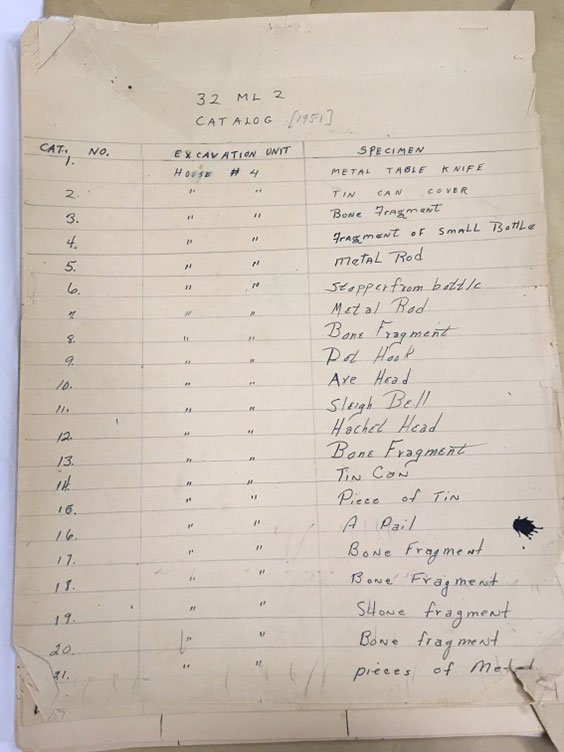

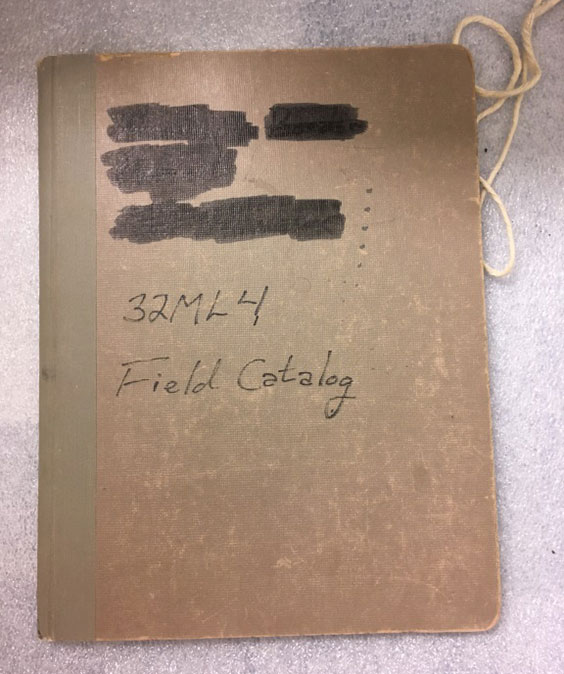

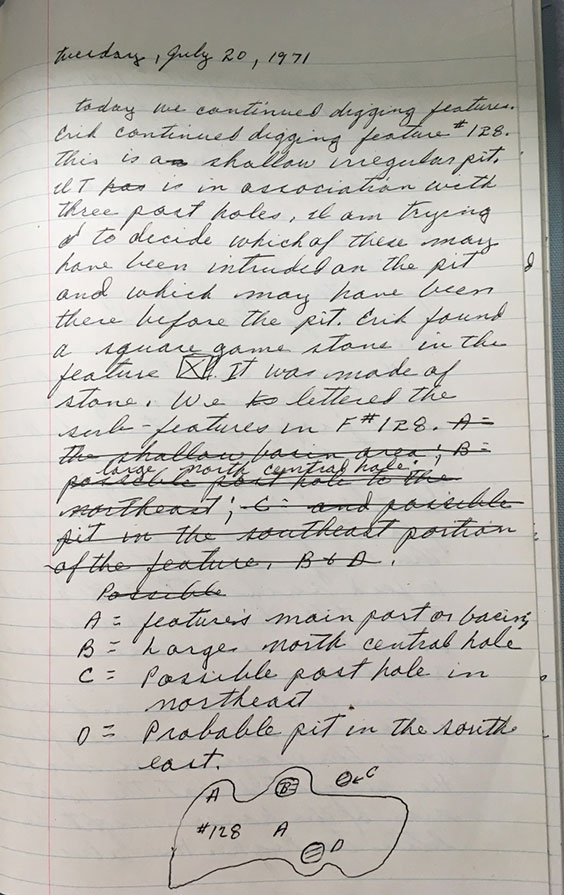

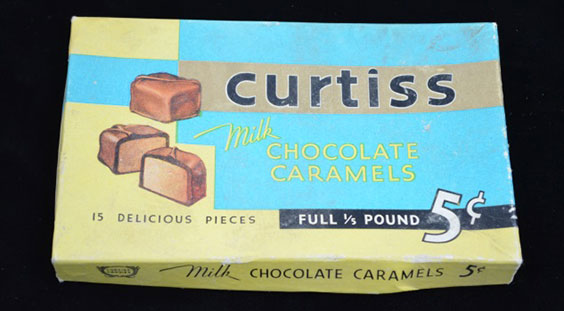

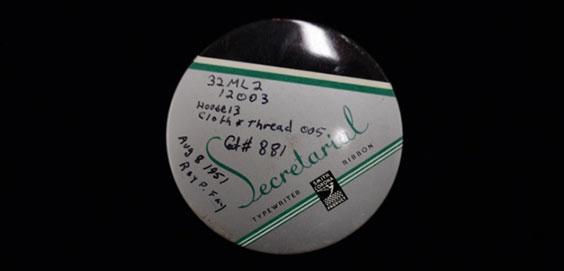

Decades ago, State Historical Society archaeologists and curators had to work with whatever resources they had, and sometimes their solutions for artifact storage and labeling are pretty creative. These are some recent examples of artifact storage that we have come across as we have been rehousing older collections. Meagan and I often wonder what we do today that will confuse, amuse (or enrage?) future curators.

Artifacts were donated to us in every kind of packaging you can imagine: cigar boxes, chocolate boxes, medication bottles, chewing tobacco tins, and typewriter ribbon containers .

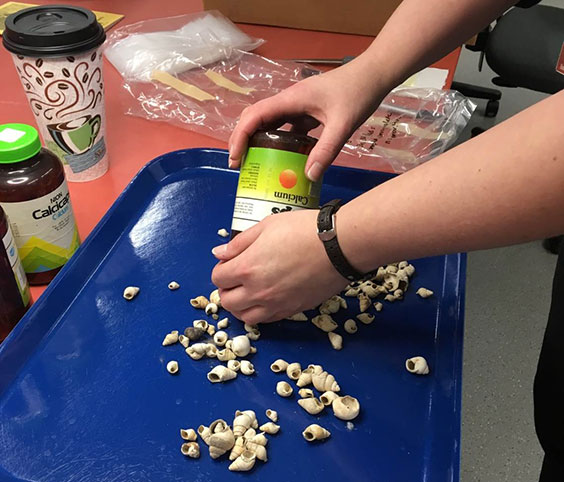

Hundreds of gastropod shells and shell beads were found inside these calcium supplement bottles.

These are not actual pills! They are tiny plastic pill vials someone used to store historic glass seed beads.

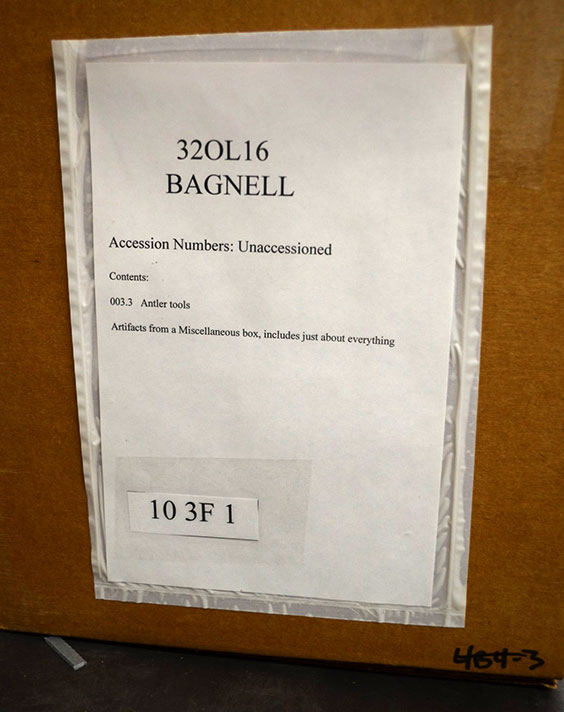

This box from the Bagnell site collection (very unhelpfully) tells us what is inside: “Artifacts from a Miscellaneous box, includes just about everything.”

We are not sure if this artifact has a history of running away, but someone thought it necessary to wrap it in about a mile of wire and attach it to this enormous tag.

3. Volunteers as Pioneers

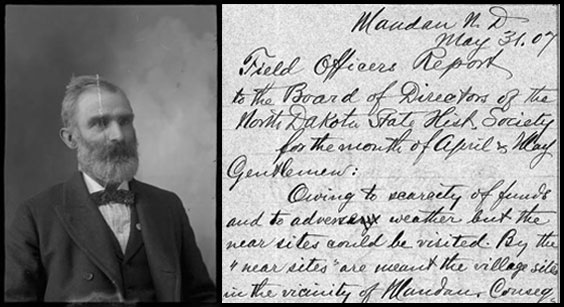

Mary Seidel, a local volunteer who started processing artifacts and archives in our lab last year, is a pioneer of long-distance volunteer work. She got so excited about lab work in 2018 that she asked for something she could do from her desert home in Nevada, so she could continue to support the State Historical Society mission during the winter. So we introduced her to Ernst R. Steinbrueck, first field officer of the State Historical Society. During the early 1900s he documented and excavated many village sites along the Missouri River. He wrote long (and sometimes ornery) letters back to Society administrators in a beautiful script that we needed transcribed, as many of them contain information about artifact collections and site locations. In less than a year, Mary transcribed scans of more than 100 letters from Steinbrueck’s papers (some of them 11 pages long!) Many thanks to Mary for not letting 1,300 miles get in the way of her passion for preserving North Dakota’s history.

A portrait of E.R. Steinbrueck, and one of his many letters curated in the State Archives.

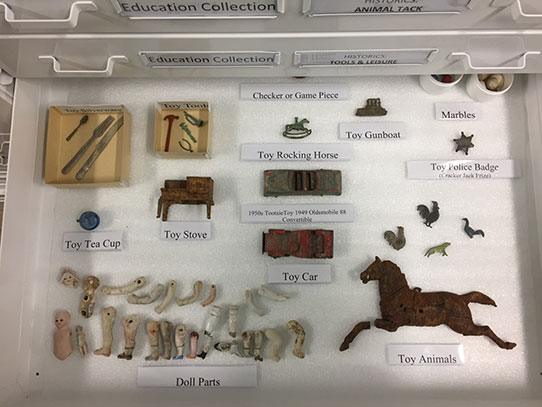

4. Creepy Doll Parts

Historic dolls provide valuable information about everything from consumerism to gender norms to the socialization of children. But as someone who has both excavated and curated artifacts, I can tell you that finding doll parts — eyeballs, legs, or heads, for instance — is also downright creepy. A few of us have bonded about this, and visitors on our tours feel the same when we open the historic toy drawer and disembodied heads are staring back at them. I don’t have much more to say about this — it is just something I think you should know.

Doll parts from various historic sites in North Dakota.

5. Thank You Notes from Schoolkids

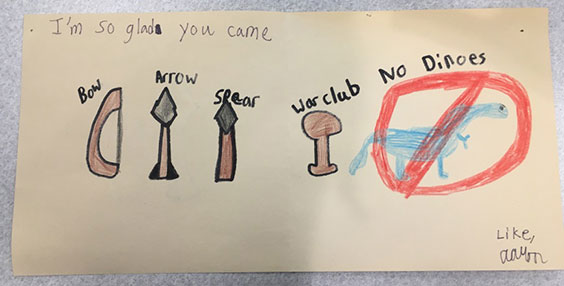

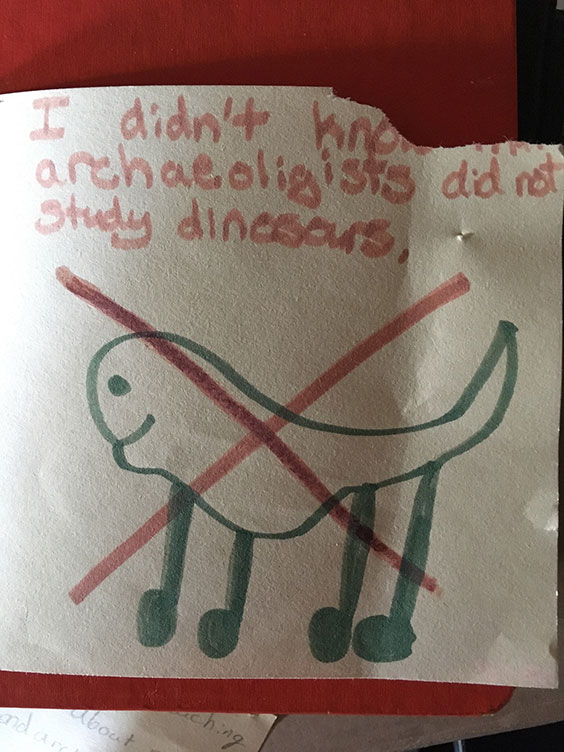

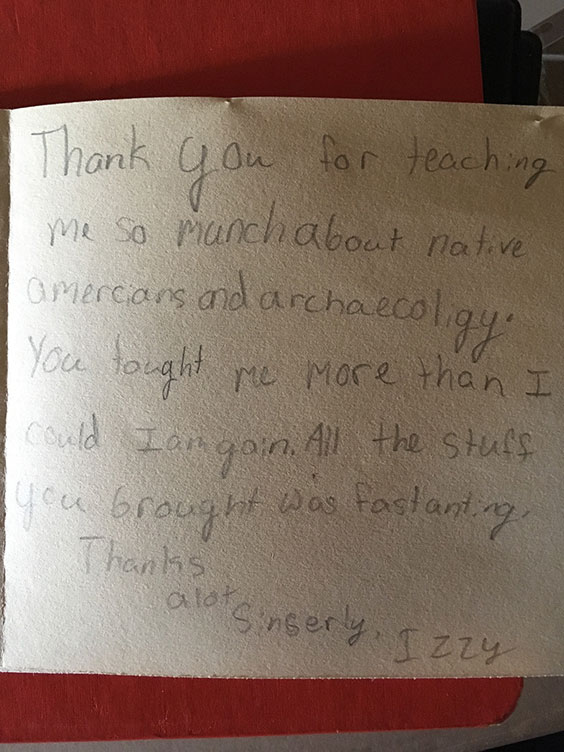

I love doing programs for school groups because kids often make excellent observations (important in archaeology!) and ask some pretty insightful questions. But my favorite part of working with school groups is getting the thank you notes a few days later. Here are some of my favorites from the last few years: