When I started work as the Pembina State Museum’s outreach coordinator in February, one of the first tasks I was assigned was to develop a roving interpretive program intended to teach school students and museum visitors about the fur trade and how the business of trading furs was conducted.

This program would take the form of a fur trading game with players assigned to either a fur trade company team or a fur trading family team. The company teams will attempt to gain furs in exchange for their goods while the family teams will have to assemble a list of items purchased from the companies to complete certain tasks with their limited furs. Among other things, players will learn how goods were exchanged on credit, how trade companies kept records, how the hunting season was conducted, and get a chance to interact with replicas of the fur trade’s material culture.

As a regular Dungeon Master who likes to make his own games, I was excited to take on the project. I had to resist the urge to break out my Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) rulebooks. D&D character creation sessions alone can run more than three hours, and our fur trade game is meant to be shorter, capable of fitting into a 1 1/2-hour time slot. But I could still draw on my experience building fun and immersive campaigns for my D&D players while developing a fun and immersive interpretive experience to be taken to classrooms and for visitors to our museum.

Immersion is key to a fun experience. To aid immersion at home I often employ props and costumes to help my D&D players visualize something. The fur trade game is like that but taken to the next level. Everything short of hunting beavers will be represented by some sort of prop, some we already have, and others we are in the process of either purchasing or making ourselves. There have been a few challenges along the way to make our ambitions a reality.

Scope is one challenge. While I would love to purchase a fully stocked trading post like at Fort Garry in Winnipeg, space, budget, and our ability to transport the game won’t allow it. Instead, I have to temper my ambitions and, in some cases, stretch less into more. We have purchased two musket flints, but two single flints do not make for a stocked shelf. So the flints will be part of an interactive display while the shelves (to be built) will be stocked with props representing the items. For gun flints, a pile of small rocks wrapped in brown paper and twine will do.

It would be nice to have shelves as well stocked as these at Fort Garry, but we have neither the space to store nor the ability to transport so much material for a roving interpretive game.

Another problem we often run into is historical accuracy. Perfect replicas of everything, like my fully stocked shelves, would be nice but aren’t always possible. We have several small pieces of printed cotton fabric. This is meant to represent calico cloth. The prints aren’t accurate, but they don’t have to be. Like props for a game of D&D, they’re meant to help players visualize something. In the case of our “calico” cloth, it’s intended to help our players visualize the wide variety of colors and patterns that were available at fur trading posts.

Purchasing large volumes of authentic calico or gun flints is unrealistic. Instead we have to find creative ways to represent these items in bulk. For instance, we’ll wrap the fabric pictured here around foam cores to give the appearance of large bolts of cloth.

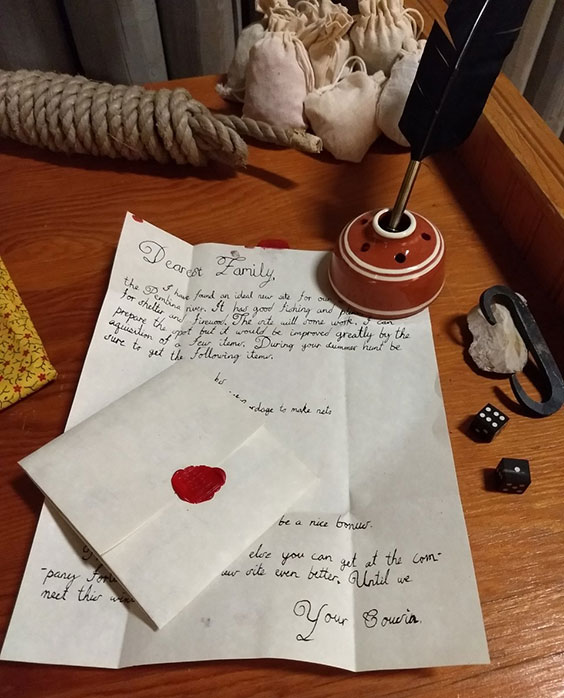

Anachronisms are unavoidable when developing certain props. To aid immersion I often use handwritten notes and letters. I intend to use them for this game as well. While not everyone who participated in the fur trade was literate, and many spoke languages such as French or Michif (the language of the Métis), our game’s participants are literate, and they overwhelmingly speak English. I will not be giving them instruction letters in other languages nor will I use period-appropriate cursive, which can be illegible to modern readers. Instead, I’ll use a cursive-like font for easier legibility. By allowing some inauthentic touches, we save on limited time.

Handwritten notes like these will add a touch of authenticity while communicating game objectives to players. They are also fun for me to make.

There’s still a lot of work to do before the game is ready for a trial run. There are certainly more challenges that await me, but I hope when the game is finished that the players have as much fun playing it as I have had making it. Hopefully, they’ll learn a thing or two as well—I know I have!