The Business of Buttons: Developing Interpretive Programs at the Pembina State Museum

While researching fur trade material culture to develop new programming and interpretation for the Pembina State Museum, I occasionally latch on to smaller details. The past few weeks I’ve been focused on the history of buttons, something most of us rarely think about. But during the 17th and 18th centuries, buttons were big business. Buttons feature prominently in collections from fur trading sites, including at Pembina. Buttons are part of our “Red River Rendezvous” program and will also be showcased in a gallery interactive currently in development.

My fascination with buttons as fur trade material culture comes from my personal experience wearing historical garments at reenactments. Today, if a shirt loses a button, we may choose to get rid of it rather than fix it. Sewing buttons isn’t as common as it once was. At reenactments and living history events, I and many of my colleagues have found buttons to be an omnipresent concern. I have lost at least one button from a coat or trousers at every event I’ve attended. Most reenactors will say the same. Given this frequency, I have learned how to quickly reattach a button between public demonstrations. I rarely read in journals from fur traders or frontier soldiers about losing or sewing buttons, but my experience with historical garments makes me think that it was so commonplace as to not be considered worth mentioning.

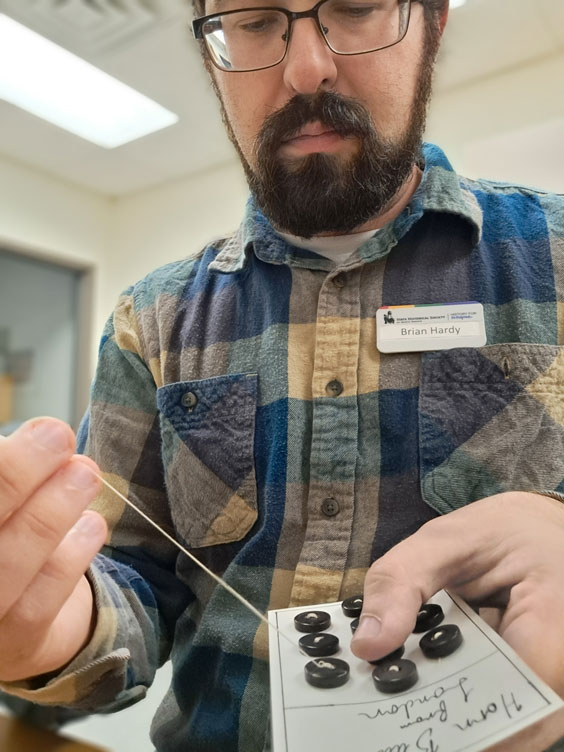

Artifacts, including dozens of buttons, collected from the Fort Pembina trading post site.

The history of buttons and button manufacturing speaks to their importance. In England, where most of the fur trade buttons for the Pembina region were made, laws were passed in 1699 and 1721 to protect the domestic button industry. Many of the firms listed on fur trade receipts were founded in the 18th century. Several new developments in button manufacturing were also made at the same time. Stamped two-piece buttons and brass gilding were both developed in the mid-18th century. Hundreds of millions of buttons were made every year in the manufacturing centers of England, France, and Italy. The Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company each ordered tens of thousands of buttons to be shipped to North America and sold to Indigenous customers. In Europe, buttons were practical fasteners of garments. However, for the Indigenous consumer, buttons were adornments for traditional garments meant to enhance the prestige of the wearer.

In this 1832 painting by George Catlin, Tchón-su-móns-ka, Lakota wife of fur trader François Chardon, wears a shawl festooned with brass gilt buttons. Smithsonian American Art Museum

The value of buttons as trade goods lasted from the 17th through the early 20th century. The “Red River Rendezvous” program interprets the value of different trade goods through the lenses of various local groups and their specific needs during the early fur trade period at Pembina. The new interactive elements that I’m working on for visitors in the museum gallery interprets value based on historical costs. The interactive will consist of a scale. On one side visitors can place weights representing beaver furs or pemmican and on the other side weights representing a variety of purchased trade goods. Guests can press a button to see whether their trade is “balanced.” If it isn’t, the scale will tip, dumping the weights back into containers.

By determining the historical prices of items found mostly in fur trade ledgers and journals, the value can be translated into weight as a proportion of their monetary value, with the value of one beaver fur or pemmican pack set at 1 kilogram. I’ve chosen metric measurements to better fine-tune the weights of different items using grams. This leaves some things a bit too heavy. In 1802, a guide in Alexander Henry the Younger’s brigade recorded being paid an annual salary of £15. Compared to the price of a beaver pelt for that same year that would make the weight representing his wages 16.5 kilograms, or about 36 pounds, which is more than a visitor should be expected to lift. A simple solution is to represent the monthly wage instead, which would be £1 and 5 shillings, or a more manageable weight of about 3 pounds. More reworking, as well as designing and prototyping, are required before the interactive is finished. We plan to have it ready by this summer. In the meantime, my fascination with buttons has yielded an enhancement to the “Red River Rendezvous” program.

Here, the author puts skills learned while wearing historical garments to work.

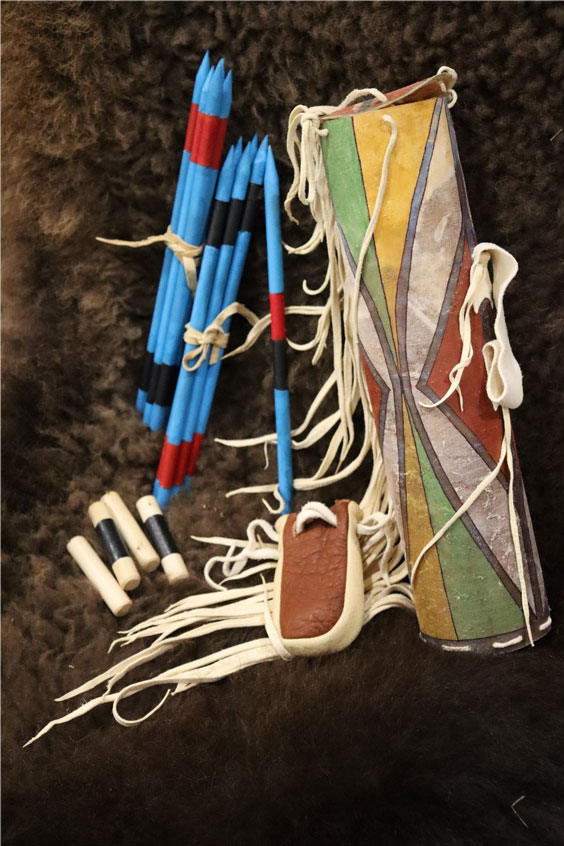

These buttons sewn to hand-drawn cards represent a small but important improvement to the “Red River Rendezvous” program, which resulted from ongoing research for a new interactive element at the Pembina State Museum.

Prior to beginning research for our new interactive, the buttons for the “Red River Rendezvous” were left in loose piles for children to handle. This often meant that the kids, when instructed to buy buttons, would trade for a single button rather than enough to complete a garment. While this offered an opportunity to talk about the historical uses and importance of buttons, our new authentic packaging helps demonstrate the typical quantity of goods directly traded. As in the past, buttons come attached to a card today. While working on the interactive, I took care to attach our buttons to cards with simple hand-drawn labels. This may seem like a trifling detail, but every improvement to the authenticity of the items used in our programs improves the interpretation and creates a more authentic experience. With each new piece of information, existing and new programs become better and better. No detail is too small.

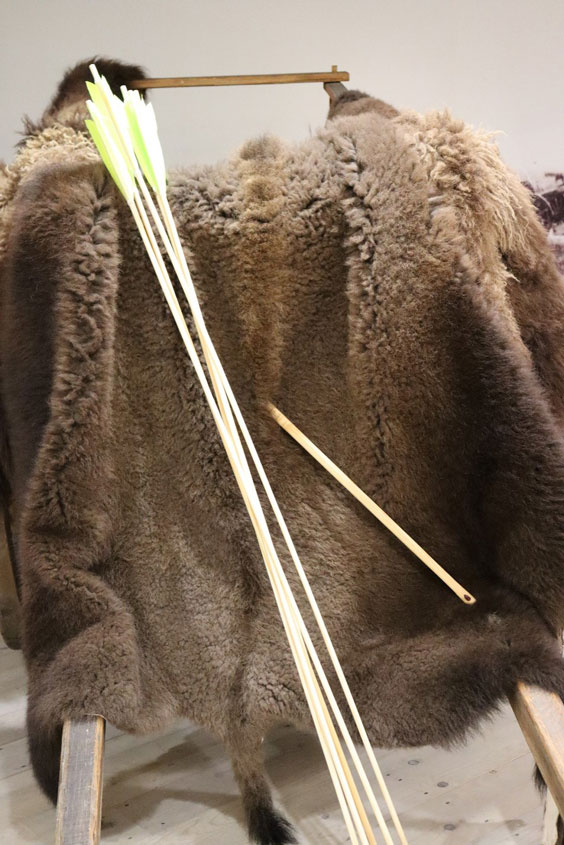

Our new button cards pictured with the other sewing items in the “Red River Rendezvous” program are now on display for visitors to interact with at the Pembina State Museum. To schedule a tour or an interpretive program, contact us at shspembina@nd.gov.