When I was in college people often asked me, “What will you do with your degree…teach?” As an aspiring living historian/reenactor, the answer I always gave was “no,” because I did not plan to become a schoolteacher or professor. But looking back on it, I realized that the dissemination of historical knowledge to people through reenactment is teaching—though perhaps not in a traditional sense.

The terminology for people who impart historical knowledge through performance varies. The hobby (as it is often called) has many faces: soldier, trapper, tinsmith, laundress, or lady, to name a few. Most people involved in historical reenacting do so for a variety of reasons. They may like camping; they may like firing historic weapons; or they may like being with friends and family. Whatever the reason, you can be certain that most people dressed in period clothes do not do so for comfort.

6th Infantry re-enactors at the Yellowstone Lodge #88 Historic Masonic Site, adjacent to Fort Buford State Historic Site. Yellowstone Lodge #88 was on the Fort Buford Military Reservation.

Wearing a wool uniform or leather tunic is not comfortable. Women who portray officers’ wives wearing corsets and several petticoats or laundresses toiling over a hot fire are not comfortable. So why are they doing this? I know a former art teacher who makes pottery and sells it at events, but he also loves the camaraderie and history aspects of being a reenactor. Others do it because they enjoy the activities associated with it, like camping, shooting, acting, or modeling period clothing. If you talk to most living historians, however, you would find that the camaraderie of the historical reenactor world is the biggest draw—meeting and interacting with others who are deeply interested in all things historical.

The majority of historical reenactors are ordinary people who relive history for fun and to get away from a fast-paced, technological world. Like anything, though, this hobby has extreme participants.

At one end of the spectrum are the “Farbs” (a fabricated impression). This is a term given to some participants who continue with historical reenactment after being politely told that their impression contains inaccuracies, like, “they would have never worn polyester” or “tennis shoes were not invented yet.” Most people will learn from these comments, often with help from fellow reenactors. They try to improve their impressions, even going so far as to research details on their own.

At the other end of the spectrum are the hardcore “living historians.” These individuals go to great lengths to make sure every detail of their outward garb is accurate. One of the contracted background artists for Gettysburg went as far as urinating into a jar full of brass buttons to get the correct patina. Most living historians, however, are in the middle somewhere (myself included). They do their research and listen to other historians to hone their impressions.

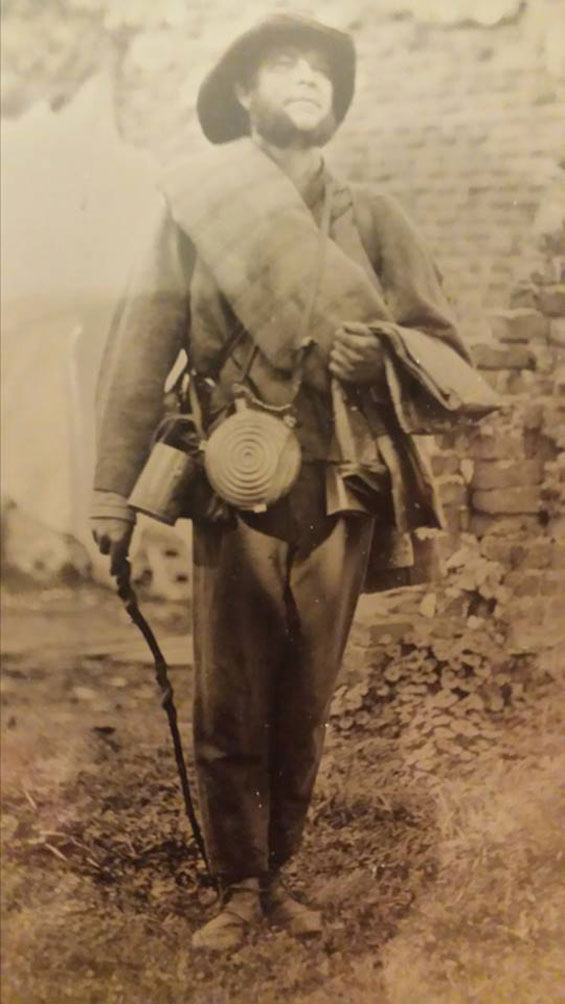

The author wearing an 1872 pleated blouse while reenacting frontier military at Fort Buford State Historic Site.

I have been a Civil War reenactor for 35 years. My own reasons for participating in this activity are simply put: I enjoy the firearms, the people, the fresh air, and the questions asked by visitors about the weapons, trappings, and uniforms.

If you have ever held a Civil War musket and looked at the workmanship of the wood and metal, you will see the amazing skill it took to craft such a firearm. There are many variations of muskets, and most were used during the Civil War. Camping with just a blanket and a dog tent is exhilarating (well, it used to be). The enormous number of questions asked by visitors and audiences is stunning. There is always one about wearing a wool uniform on a hot day, “Aren’t you warm in that?”

As his name implies, Robert Lee Hodge is reenacting a Confederate soldier. He looks and acts the part of a underfed, clothes scavenging, hard core Confederate veteran soldier.

It is wonderful when the questions someone asks are about something I know very well, and about which I can provide a lot of information. For me, that would be any question about Fort Seward, strategy during Gettysburg, or any other major battle of the Civil War. “Do you think Robert E. Lee was off his game during Gettysburg?” (Yes.) “Could the South have won with Stonewall Jackson?” (Yes.) And if the answer to a question is not clear, it makes me curious. I then go read the relevant historical accounts to glean an answer, if there is one. With those questions, I usually answer like any teacher would: “That is a good question. I don’t know for sure, but will look deeper into it.” In this sense, living historians are also lifelong learners. The truly best questions come from young people. It thrills me to answer their questions. From these encounters, I always feel there is hope that the work that living historians do to preserve the past will continue.

Next time there is a living history demonstration going on near you, I recommend that you watch and ask questions of the participants. You will see the light in their eyes and the passion they carry in their hearts for what they do.