If you are like me, you think that software, as a general topic of discussion, is boring. Few people interested in history and anthropology are drawn to blog posts about software (notice that I didn’t include it in my title, for fear of you abandoning me before I could get a word in edgewise). But what if that software allowed you (literally, you) access to our collections from exactly where you are sitting right now? What if it connected close-up photos of artifacts directly with that object’s records? What if it made collections research more possible, allowed us to put together exhibits much more easily, and allowed us to search across multiple collections at once?

Each of our divisions currently manages its collections in separate types of programs and databases. For example, a researcher interested in Fort Clark would currently have to come to the Archaeology and Historic Preservation Division to search separate databases/shelves for artifacts and excavation notes. Then she would go to the Archives Division to search for historical records and photos associated with the site. Then she might want to check with the Museum Division to see if there are historical objects that relate to the site but were not found archaeologically.

We are happy to report that this wild goose chase is all about to change!

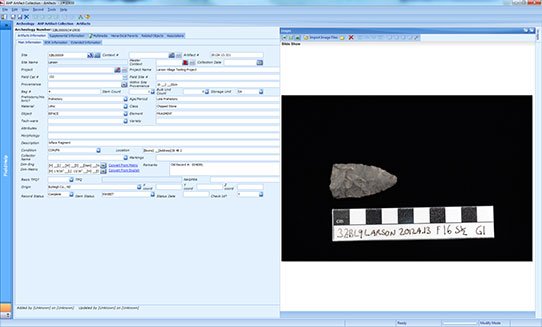

Example of an artifact record after our customizations were implemented. All the fields you see correspond directly to either a field that was already in our existing databases or a field we always wished we had.

The SHSND has recently purchased Re:discovery, software designed specifically for museum collections management. Why is this important? Managing any collection requires us to have updated and easy-to-access information about each object. An artifact record might include where it came from (i.e., Double Ditch Indian Village), where on the site it was found (i.e., “floor level, House 4”) who donated it, its function, its condition, its characteristics, pictures, etc. Under the direction of our astonishingly patient and meticulous IT administrator (whom must secretly feel that working with historians who cling fiercely to ten almost-identical versions of the same database because they are afraid to throw anything away is maddening), we are implementing this software in phases. Our AHP Division was the first up, and here is how it went down:

- First we had to create our artifact record screens. Re:discovery has a standard one already, but some of the fields did not work for our data. So we requested customizations. We wanted the names of certain fields changed, we wanted certain fields to only allow certain entries, we wanted dates formatted a certain way, and so on. This was made more complicated by the fact that we curate for federal agencies, which have their own database entry requirements. To keep everything organized, we created a “mapping document” that accommodated all SHSND required fields, all federally required fields, and were formatted to receive our existing data in ways that would not create a huge mess or data loss. This process took several months of making requests and corresponding with Re:discovery to figure out what was possible.

- Screens customized and approved! Time to move on to data conversion. This just means that we had to move the artifact data we have put in a bunch of disparate Access databases over the years into a single directory in Re:discovery. Let’s be honest – this was a nightmare. As with most institutions, people entered different types of data in different ways over time. So in one database, for instance, the location information (i.e., Excavation Unit 10) might be in a field called “location,” and in another database for a different collection, it might be in a Description field. So you can’t just say “all Description data in our Access fields can be migrated into the Description field in Rediscovery” (because you want location data in your fancy new Location field). So you have to reconcile all those discrepancies before you can migrate data. And we are talking tens of thousands of records. We also had to make decisions about what information got moved and what could be dropped. For example, some collections staff would write their thoughts in the Description field, like “I have never seen one of these before” (Is this really informative and worth saving?). In some cases the entry to describe the object tells you more about the context of its use rather than its function. For example, instead of calling a military button a “button” in the Object field, it said “Military” – not ideal when you want to search your database for buttons! This phase forced us to make some standardizations and changes in our cataloging procedures. I definitely had moments where I felt like we were in an endless loop of adjusting and converting our data, and maybe I just had to accept that this was what the rest of my life was going to be…

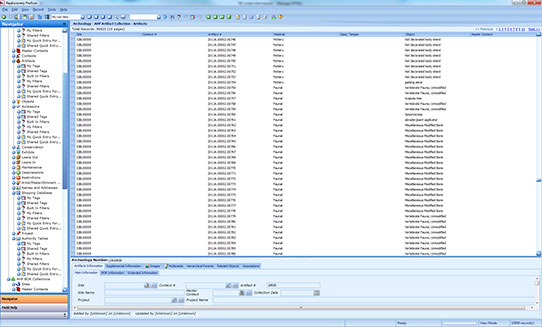

A list view in Re:discovery. Instead of viewing individual artifact records, you can scroll through lists of artifact records, all of which can be filtered by whichever fields will give you the info you need (i.e., I can search for all artifacts from the Larson Village site, or all the bone beads from Larson Village, or all the scapula hoes from Larson, Boley, and Sperry Villages. The search options are endless, which brings tears (of unabashed joy) to my eyes.

A list view in Re:discovery. Instead of viewing individual artifact records, you can scroll through lists of artifact records, all of which can be filtered by whichever fields will give you the info you need (i.e., I can search for all artifacts from the Larson Village site, or all the bone beads from Larson Village, or all the scapula hoes from Larson, Boley, and Sperry Villages. The search options are endless, which brings tears (of unabashed joy) to my eyes.

- At last, data converted! But we couldn’t just assume it all migrated perfectly. We had to check the data conversion to make sure data migrated safely and was not lost. This amounted to tens of thousands of records, and checking each one individually was not possible. Instead, we calculated a statistically representative sample for each database, which means we ended up checking about 200 to 300 randomly selected records for each one (amounting to about 1000 entries). We compared every field (thirty or so) from the old database with those in the new and noted any inconsistencies, formatting weirdness, mix-ups, etc. Any problems we found in the conversion we communicated back to the IT administrator and Re:discovery project manager, who adjusted the program or data as needed.

Some artifacts we have recently entered into our new system – stone scrapers, a historic bottle, and a pottery sherd from the Woodland period decorated with a cord-wrapped stick.

- Home stretch! Last steps were to set permissions for which staff can access or modify the data, document problems with our own data that this process helped us to discover, and get formal training on how to use the program.

As of last month, we began actively cataloging multiple archaeological collections, attaching digital photos of artifacts, geeking out on the program’s functions, and forcibly stopping ourselves from doing cartwheels in the lab from excitement that we can now do this work in one place so efficiently. Next up is the Archives Division, followed by the Museum Division. After that, we will work on getting the Web Module up and running so the public can search our collections online, complete with images. Our goal is to bring the collections to you. You can see for yourself all the objects we are preserving, without having to leave the comfort of wherever you are sitting right now. Stay tuned!