Artifact identification and analysis is central to what we do in the archaeology lab. But most of us do not always know exactly what we are looking at – and we would not be very good scientists if we pretended we did! So how do we figure it out? What do we do when we do not know, for instance, what kind of lithic (stone) material was used to make a projectile point, or what kind of shell was used to make a bead? That is where our reference collections come in.

One drawer of many in our lithic comparative collection. The loose tags inside are for use in photography.

A reference collection is a grouping of specimens that have been thoroughly researched and identified by an expert in that field and labeled accordingly. Think of it as a 3D encyclopedia. With anything I can’t identify on my own (or maybe I just want to be more confident about my identification), I could compare to examples in the reference collection until I find the match Okay, it doesn’t always work that tidily, but you get the idea. Over the past few months, I have been working with my co-worker, Amy Bleier, and some of our volunteers to get the lithic comparative collection organized and ready for use by researchers and contractors. But you may be wondering… why would archaeologists find a collection of different types of stone useful?

Lithic raw materials have unique mineralogical signatures that allow you to trace them back to their source (e.g., an outcrop of rock in eastern Montana). So if you know that someone at a hunting camp in eastern North Dakota was making tools from a stone that originates in Colorado, then it tells us something about human mobility during that time, and/or trade relationships between those hunters and groups in distant areas. We can also find patterns – for instance, the raw material that people use may change over time (directing us to look for changes in other behaviors, such as subsistence or settlement). Or people may only use a certain material for particular classes of tools – this helps better understand tool technology and specialized knowledge relating to flintknapping.

Physically assembling a collection likes this is the most difficult and time-consuming part. We were fortunate to receive a donation of a completely assembled lithic comparative collection from the late Stanley A. Ahler, Ph.D., whose work in the region laid the foundations for the last thirty or so years of archaeology in North Dakota. Over many years, Ahler, with help from his colleagues and acquaintances, collected more than 280 lithic samples from across the United States. We regularly rely on this collection for lithic analysis. But now we want it to be useful to people who can’t come to our office when they need to compare different types of raw materials.

With the help of SHSND volunteers Doug Wurtz and David Nix, we have taken high-resolution photos of all specimens, written narratives on their origins and characteristics, created finding aids, and compiled a bibliography for the 16 most commonly found materials in North Dakota. The next step will be to create an app for mobile devices so archaeologists and other researchers can take advantage of the collection while they are in the field or doing analysis in their own labs.

Antelope chert is silicified peat that occurs primarily in non-glaciated areas southwest of the Missouri River. It comprises woody plant materials and can contain whole or fragmented gastropod shells. The type site (and quarry) is in McKenzie County, North Dakota.

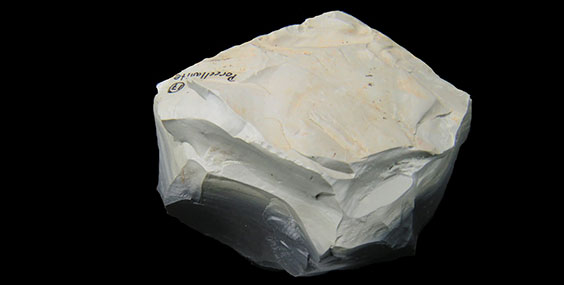

Porcellanite is vitrified claystone and shale that forms around burned lignite seams. The source area is concentrated in southeastern Montana, northeastern Wyoming, and western North Dakota.

Knife River flint originates in Dunn and Mercer Counties, North Dakota, though cobbles can also be found in gravel deposits in the southwestern part of the state. It is typically brown, fine-grained, and develops a yellowish-white patina on exposed surfaces.

Because there can be a lot of color and texture variability in one lithic type, we will include multiple images when necessary to depict variations. Feel free to make suggestions as to how we can make the app useful to you. We will let you know when it goes live.