This might be one of the most frequently visited questions in my household. Some examples: Why did Germans support Hitler when he was so terrible? Why did humans enslave other humans? Why did George Washington believe that bloodletting would get rid of his sore throat (it killed him)? Why were some women anti-suffrage? How was child labor justified during the Industrial Revolution? Why do fools fall in love?

There are many curious minds in my household, including a wide range in the ages of our kids and young adults. Despite (or because?) of this broad span of perspective, these “why” questions come up a lot.

When they do, the easiest solution is to check my phone; but the easiest solution might not be the best. There are fascinating videos online about the algorithms Google and other search engines use to produce top results when you ask “Hey, Google” or “Alexa. …” But--are the top results accurate? Paid for? Unbiased? Politicized? Do Google results tell you correct answers?

In addition to questions of the reliability of search engine results, it is easy to get lost in a rabbit hole of responses, chats, debates and “expert” answers online without ever coming up with a solid answer.

As an archivist and lifelong learner of history, I am especially grateful during those “why” times that archives, libraries and museums exist. Because of the work of these fields and members of the public who contribute to them, we have access to answers to some of our most burning “why” questions.

Archives (and other cultural heritage institutions) and their supporters are a partnership: Archives could not preserve and provide access to human history without members of the public who see the current and future value in the movies, photos, book, documents and artifacts they donate to public institutions. Simply put, private archives would not exist without donations of important historic materials from their constituents.

The more we save, the more data we will have to interpret in the future. We will have a greater firsthand spectrum of the human experience and reasons for why people did that. If we rely only on published sources to tell our stories, we might miss out on the unique perspectives and voices that make us interesting as a species. Like anything else, published sources are a product of their times, and are written through the socio-political lens of writers and editors, biases and all. Firsthand accounts can provide raw data that can be analyzed and interpreted across time and cultures.

I’m not sure whether other generations anticipated these “why” questions. Based on the records they preserved, I think that many did.

I often wonder how future generations will view our time. In this “information age” there will likely be a ton of information for them to sift through. However, as in the case of search engine results, quantity does not always equal quality: How much of the available information will be by the people who lived it? If my great-grandchildren ask how we felt during COVID-19, what it was like to go to fourth grade during a pandemic, or why wearing masks was politicized, will they get their answers from a news site (which we know often report differently based on political affiliation)? Will they read comment threads on Facebook? Will they watch news clips of the various responses of political leaders?

Maybe it’s my bias, but my hope is that future generations will have access to read/hear/watch the voices of the many who experience an event like COVID-19 firsthand. The best way to do that is to start documenting daily experiences, even if they seem trivial or mundane. It is the experiences of daily life that future generations will relish for their authenticity and rely on to answer their own “why” questions, whatever they may be.

I think there is a misconception that you have to be a George Washington to be preserved in archives. This couldn’t be further from the truth. This idea prevents people from documenting their lives and experiences, which are the building blocks of history, the keys to understanding life and events of the past. The more voices that are available, the better understanding that future generations have of our time. I’ve included two examples below of materials that could be collected by the State Archives: records that my family kept during COVID-19 and a collection of newspaper clippings about the coronavirus pandemic that were collected and donated to the Archives by a North Dakota resident.

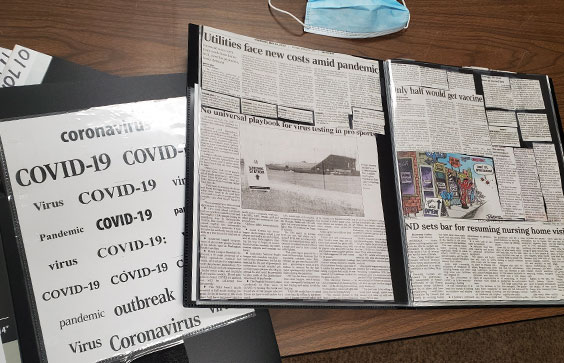

Coronavirus pandemic-related news clippings from a variety of sources that will be a resource for future researchers about North Dakota history (MSS 11450).

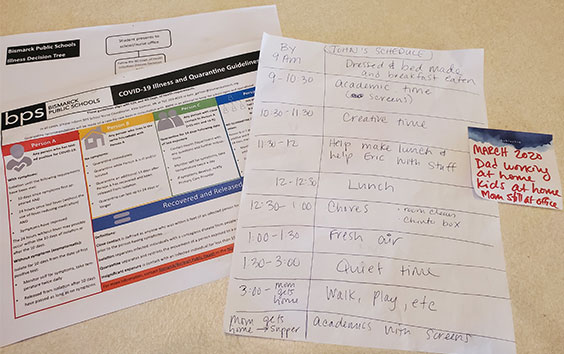

My family’s schedule for our 9-year-old son during the early stages of COVID-19 in North Dakota.

If you are interested in donating your stories related to COVID, please use this link. We all play a part in preserving today to answer the “why” questions of tomorrow.