There is a lot to consider when developing a new program at a state museum. Who is it for? What is it meant to teach? How will that message be conveyed? Where will the program take place? Why is this topic important? On top of all that you must consider what resources are available and what safety guidelines need to be followed. Ultimately, what you want most is for participants to be engaged and eager to learn. In my experience participants seem the most engaged when they are having fun. And what better way to accomplish this than with games?

I am currently working on a program called “Games from Pembina’s Past,” which includes a short virtual element for classroom use and a longer element that will allow visitors to the Pembina State Museum to play various games from the different peoples that settled at one time or another in the region, including the Anishinaabe, Dakota, Métis, Scots-Irish, Icelandic, and others. The program is in the early stages of development. We’re gratefully receiving tribal input regarding the Indigenous games that are included to ensure these are portrayed appropriately and respectfully. Stewart Culin’s “Games of the North American Indians” has also been helpful to my research. The book provides key details such as the Indigenous names for games, designs for the game pieces, and rules for play.

The first game I worked on was hoop and stick. According to Culin, the Chippewa of the Turtle Mountains called it tititipanatuwanagi. It was played by two competitors, one of whom rolled a small hoop ahead of themselves while running. The two competitors would throw their sticks, which had forked ends or were decorated with feathers, at the webbing woven around the hoop. Points were awarded based on where the stick struck in the webbing, much like darts. No points were awarded if the stick passed completely through the hoop.

Students visiting Fort Mandan State Historic Site play a version of hoop and stick. We hope to have students playing the game here at the Pembina State Museum very soon.

The difficulty of the game can be adjusted by changing the size of the hoop. Historically, hoops have ranged from two inches up to two feet in diameter. So far, I’ve made one 12-inch hoop for the museum based on a 1903 artifact from the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians. The original is currently held by the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. In the coming weeks, I plan on making a few more hoops of varying sizes.

Pictured here is a hoop and stick set I made for the interpretive program using an embroidery hoop woven with artificial sinew to create the web pattern. The sticks are simple painted wooden dowels, with a feather attached to the end with more artificial sinew.

Culin groups different North American Indigenous games into broad categories, which prompted me to compare Indigenous games with games played by European settlers that fit into the same categories. I mentioned that hoop and stick shares some similarities to darts. Other comparisons can also be made. One that I make in the virtual element of the program is to compare a category of game played on an icy track that Culin “included under the general name of snow-snake” (which is also the name of the game itself) to the sport of curling.

Snow snake was played by almost every tribe in the colder climates of North America. The game was played with long, slender pieces of wood carved with heads resembling snakes. Another similar game that Culin includes under the umbrella category of “snow-snake” is ice gliders, also called bone sliders by Culin. Ice gliders were made with animal ribs and decorated with feathers. Snow snakes and ice gliders are slid with an underhand motion along an icy track, which has been prepared beforehand. The Chippewa often built these tracks by dragging a log through the snow and sprinkling the resulting trough with water to create an icy playing surface. Points are awarded to the player whose snow snake travels the farthest in each round.

Culin classifies snow snake as part of a category of games in which game pieces are “hurled along snow or ice.” In the case of snow snake, the pieces are often similar to darts or javelins. This type of game has obvious comparisons to curling, a team game played by sliding a large stone down an icy track toward a target area. I hope to help bridge a cultural divide for students by comparing something familiar, like curling, to something that isn’t, like snow snake or the ice glider game.

A set of ice gliders, or bone sliders, made by the staff of the Lewis and Clark Interpretive Center.

More familiar to many North Dakota students than curling (and immediately recognizable to the Scottish settlers who built Fort Daer in Pembina in 1812) would be field or floor hockey, also known as shinny. Shinny refers to any game of field hockey where players use curved sticks to bat a ball through goalposts. The name shinny comes from an older Scottish Gaelic word, shinty, which is a game related to hurling and is of prehistoric Celtic (Irish/Scottish) origin.

European and Indigenous field hockey are uncannily similar, which may be why the Indigenous game bares the European name in Culin’s book. The Assiniboine name for the game is tah-cap-see-chah. Shinny was a common tribal game throughout North America. During the game, a buckskin or wooden ball is batted about with curved sticks by two opposing teams. According to Culin, the buckskin ball, weighted with clay or filled with cloth scraps, is the most common ball used by Plains tribes. Players are prohibited from holding the ball but in some versions of the game rules permit the swatting or passing of the ball with the hand. The object of the game is to pass the ball through a goal, usually a pair of stakes set at either end of a flat playing field.

Currently visitors to the Pembina State Museum can play hoop and stick, the hand (or stick) game, a type of guessing game, which we purchased from Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indian artists, and double ball, another field sport like shinny which involves passing two balls bound by hide or string back and forth using sticks. Like shinny, the goal of double ball is to get the ball to a goal at either end of a playing field. We also have a few settler games available including hoop trundling, which involves rolling a hoop along with a stick. (Children would often race each other as they rolled the hoops.) Visitors can also try their hand at jacks and marbles, which though sometimes played today has waned in popularity. Research continues into what other types of games were played in the region both by Indigenous people and those of European origin. While we don’t have the facilities to include curling among our offerings, we do intend to add field hockey in the very near future.

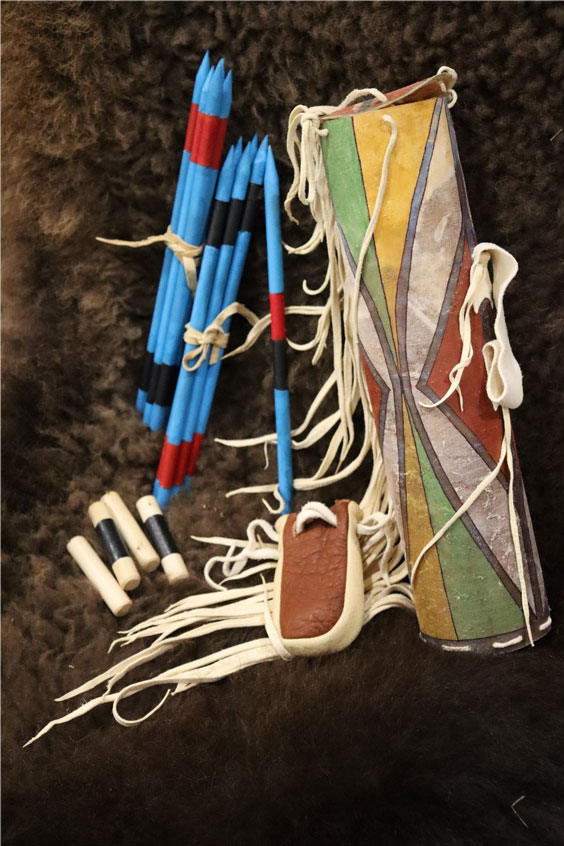

This handcrafted stick game set came from the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians and is available for visitors to play at the Pembina State Museum. In this guessing game, one team of players hides both black and white pieces in their hands. The other team must guess which hands hold the black pieces. Score is kept by passing sticks between the teams until one team wins all the sticks.

While many of the European games like curling, field hockey, and darts are still played today, their Indigenous counterparts have been mostly forgotten over the past centuries as tribes were expected to adapt to Western culture. But there are many efforts to revive these games. One example is the Ojibwe Winter Games held annually since 2012 at Camp Nawakwa near Lac du Flambeau in Wisconsin. The games were started to educate students about the history of Native sports. Snow snake, hoop and stick, atlatl throwing, and many more Indigenous sports are played by school students during these winter games. In some small way, I, too, hope to spark interest in Indigenous games at Pembina State Museum through the development of our new program. After all, sports and games are universal pastimes that unite people around the world.