What does an archaeologist do?

First hint: We do not look for dinosaurs.

Paleontologists study dinosaurs and other fossils. (We regularly ask the paleontologists who work for the North Dakota Geological Survey questions about fossils.)

Archaeologists do not dig for dinosaurs! Paleontologists do that.

Second hint: We do not hunt for treasure.

This is often how archaeologists are depicted in movies, television shows, and books. They are usually searching for rare treasures that will make them rich and famous (think Indiana Jones). And when they find the treasure, they grab it and run. A real archaeologist doesn’t do that.

So what does an archaeologist do?

Archaeology is about people and the study of the human past. Archaeologists are scientists interested in learning more about people and how they lived—whether 50 years ago, hundreds of years ago, or thousands of years ago.

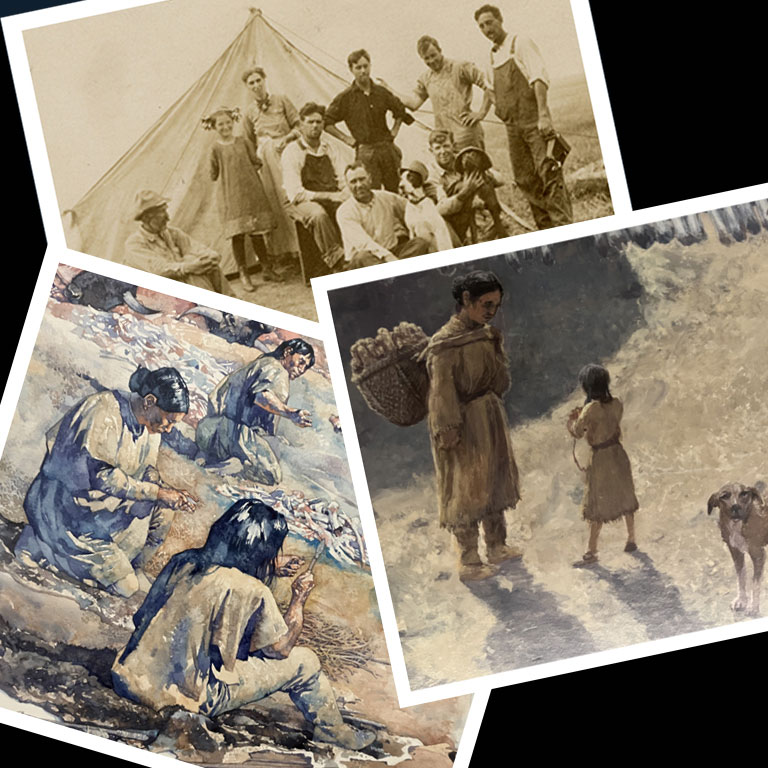

Bottom Left: a detail from artist Greg Harlin’s painting of bison hunters at Beacon Island thousands of years ago. SHSND

Bottom Right: a detail from Rob Evans’ cyclorama of Mandan people living at Double Ditch Indian Village hundreds of years ago. See it in the ND Heritage Center & State Museum’s Innovation Gallery: Early Peoples. SHSND

Top: detail of a group of people from an undated photo taken in the late 1800s-early 1900s. SHSND SA 11636-00041

One of the ways we learn about how people lived in the past is by studying artifacts. Artifacts are anything made, used, touched, carried, or modified by people. Artifacts are little clues that help archaeologists understand how people lived and interacted with the world around them.

An Agate Basin projectile point—similar to the cast on the far left—is an artifact. But so are the fire-cracked rocks, charcoal, and ash in the center. The pull tab and piece of concrete on the right are examples of recent artifacts. SHSND AHP educational collection

Besides artifacts, we also learn from features. Like artifacts, features were made or used by people. But unlike artifacts they can’t easily be removed. Foundations from old buildings, post holes, and hearths or fire pits are all examples of features.

Top: a hearth (left) and three post holes (right) at Fort Clark State Historic Site.

Bottom: an historical house foundation built on top of the Hidatsa village at Molander Indian Village State Historic Site.

Both images show examples of features.

Two of the most important aspects of archaeology are provenience and context. Provenience is where something is found. Context is what is found around it. This is important for both artifacts and features. Provenience and context give us even more clues as to how people lived in the past. An artifact without provenience or context lacks the clues that help tell the story of the people who used it.

These artifacts are unprovenienced objects (we do not know where they were found). Most likely none of these objects even came from the same place. They are fun to look at. But we can only say a few things about them—that they are “old” and mostly from the mid-to-late 1800s to early 1900s.

Unprovenienced artifacts from the Archaeology & Historic Preservation Department’s educational collection. We do not know where these were found. Top: wagon wheel hub wrench; middle row: a horseshoe, a suspender buckle, and flat window glass shards; bottom row: glass and shell buttons, nails, and watermelon seeds. SHSND AHP educational collection

It is major part of an archaeologist’s job to make sure the provenience and context are recorded. When an artifact is removed from a site or a feature is destroyed, the context is gone. We can never get it back. Because this information is so important, archaeologists record data in many ways. They keep notes about what they do, what they see, and where things are found. They record measurements of features and objects. They take a lot of photographs and keep photologs. They create sketches. They record locations by making maps and using tools like GPS.

All this information is usually compiled in a report. The end goal of archaeology is to preserve information about the past and to share it with others in the future. Sometimes this is done with a book or publication. Other times it is done with exhibits, posters, or even blog posts.

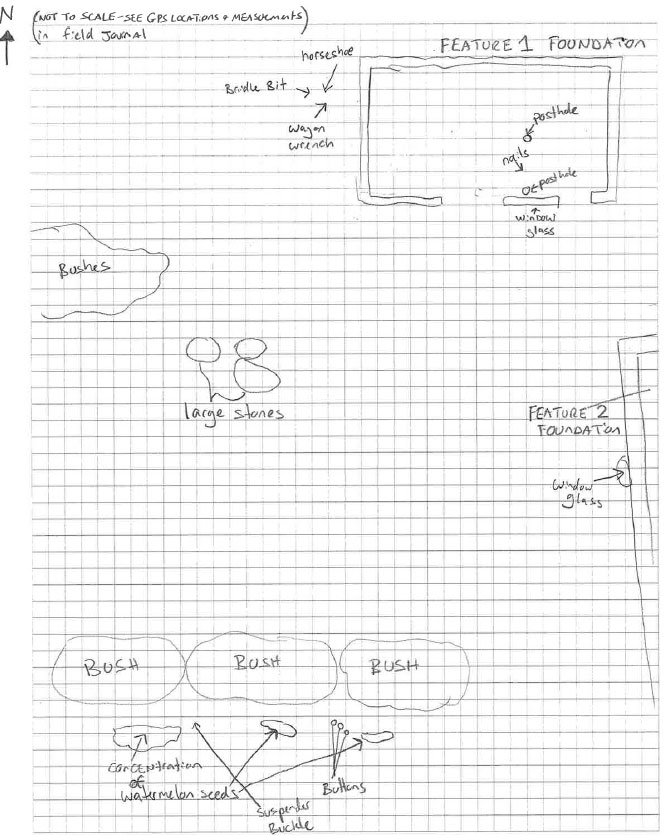

Let’s pretend an archaeologist excavated the artifacts in the previous photograph. They recorded everything in their field journal, took photos, and recorded measurements of the features and artifacts. They also recorded information on a simple sketch map like this.

Recording the location of artifacts and features in a sketch map is a key part of what archaeologists do.

With the information from the scenario above, we could be looking at artifacts and features that tell a story like the one in this photograph. Knowing where artifacts and features were found in relationship to each other helps tell the story of what people were doing in a specific place and time.

A watermelon party near Larimore around 1905. SHSND SA 00032-GF-22-0002