Here in the Archives, we get a lot of questions asking how researchers can access information. Specifically, we get a lot of requests for digital files, preferably accessible on the internet, searchable by keyword, easy to use, easy to find.

We live in an age of easily accessible research, so it is what is expected. It is not, however, something we are able to do at this time. We don’t have the staff, the time, the funding, or the storage space to host such massive collections online.

A lot of our information is readily and easily accessed, though the majority of our collections are not digitized, online or searchable by keyword. Many researchers get ideas of what they need when looking at an index of collections on our website. You do have to be present to access most of our collections, or at the least, pay a minimal fee for a search, borrow a reel of microfilm through our Interlibrary Loan program, or some other similar research.

Yet this is nothing compared to what researchers encountered in the past. Digging in can be tough at times; daunting, even. Research can be challenging, and it can be rewarding—but it can also be arduous.

The State Historical Society of North Dakota has roots going back to the late 1800s.[i] For many years, it existed as a shadow of what was to come within other buildings on the capitol grounds. The Archives didn’t exist as a separate division within the society until 1971 and did not have a specific location where the public could easily access the collections. The move of this agency into a new building, its current home, offered opportunities to disseminate history in many different ways, including a public access area into the State Archives (our Orin G. Libby Memorial Reading Room).

On February 2, 1981, Jim Davis, current head of reference, opened the Reading Room of the State Archives for the first time. In doing so, he ushered North Dakotans into a new world of research possibilities.

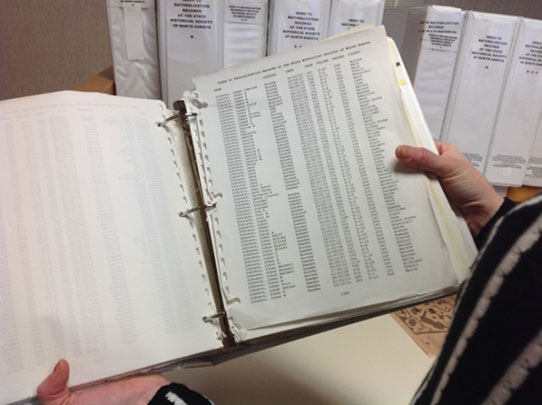

As you can see, these books are large and heavy. This one is about half the size of a semi-average-in-height Archives professional.

These paper indices are nice to use, but it is more difficult to check out different or partial spellings of last names. If you don’t know the last name—forget it.

Here is the famous and fabulous microfilm machine. This is the old version.

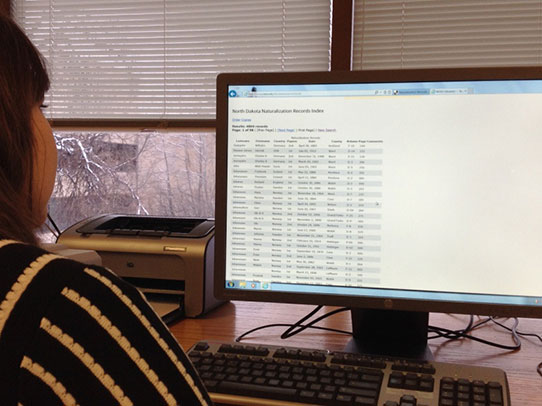

Here is the naturalization index, online through the Institute of Regional Studies. This makes it a lot easier to access and search.

Jim tells me many stories of how things were done differently in these early days, as he has been around this agency longer than I have been alive—as I kindly point out to him. Even if he didn’t tell me these things, the composition of the building itself would. For example, we have a startling lack of accessible outlets in our public research room. When the building was built in the 1970s and 1980s, people did not bring computers and cameras and phones in with them. They may not have even had all of these items at their homes. Outlets weren’t as much of a necessity then. Things have changed.

Case in point: In 1985, a state law was enacted that naturalization records had to be transferred from the counties to the State Archives. After they arrived here, if someone requested a copy, staff would have to go up into the stacks area, find the person in the index (if there was one), bring down the book, and copy it on our copier. These books were large and heavy, and you had to be careful not to tear the book in trying to get the correct spot copied.

When I started working here as an intern in 2006, the names were indexed alphabetically, and the books all microfilmed. This means that when I started here, I could locate a name in our alphabetical paper index, find the roll, and make a microfilm copy on one of these old (but much loved) clunkers of a machine and print out a page.

Today, I can go onto our website, link to the Institute of Regional Studies, search a name partially by typing in part of their name (great for those that often get misspelled), find the roll, pull it up, put it into one of our new microfilm scanners, and save it as a pdf or print out a page. I might even be able to find some article about the naturalization or some other life event of the individual by typing their name into Chronicling America through the Library of Congress and searching randomly through the available years/locations of newspapers. I might type their name into our searchable webpage and find an oral history or photograph collection linked to their name.

Or even look back at Wendi’s recent blog post, “Our Collections, Coming to a Computer Near You,” about how we are working to link different collections in the building. How cool is that? The concept is that we will be able to search everything in this building with a few keystrokes. Everything! (Insert evil laugh here.)

Of course, there are some trade-offs to this great excitement. It still won’t be as easy as typing a string of query words into a toolbar and accessing every document online. It is easy to admit that some of the burden of research has lifted…although still not everything is searchable, not everything is indexed, and we get more to add to our collections every day.

Isaac Newton is attributed with the quote: “If I have seen further than others, it is by standing upon the shoulders of giants.”

I could point out that I found the exact wording of this quote by typing in “quote standing shoulders” and searching Google—but let’s cut to the point. We are all standing on the shoulders of those pioneers of the past, just as they stood on the shoulder of their predecessors. Just think of where we will be in the future.

[i] There is a long history to the development of the State Historical Society of North Dakota, which has recently been covered in the 2015-2017 issue of the North Dakota Blue Book, so I will not go into much detail in this blog post.