Life of a Fossil: From Death to Exhibit

Have you ever thought about how the many dinosaurs on exhibit in museums across the country got there? What is the journey taken from the time the animal dies until it goes on display? Do all animals become fossils? If the path to becoming a fossil begins at the moment of death, then every plant and animal must run a gauntlet of forces, any of which can stop the process of fossilization.

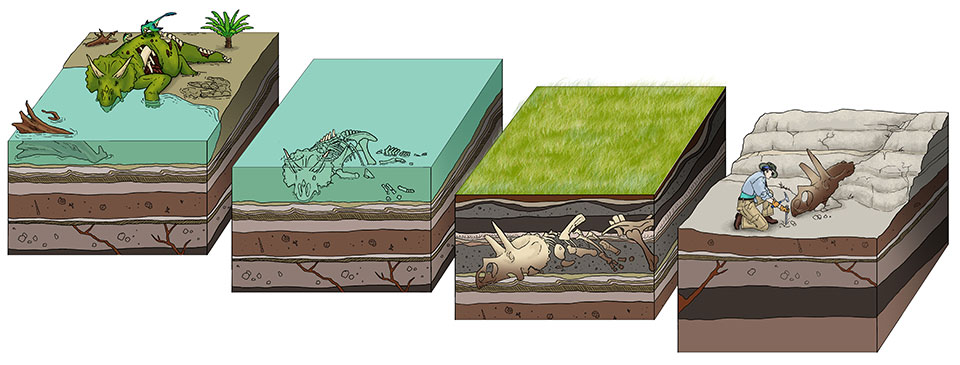

Picture a Triceratops during its last day on Earth. After giving up the ghost (so to speak), a plethora of forces will begin attacking the future fossil.

First, the Triceratops might be exposed to animals that would like to make a meal out of its remains. This would include scavengers spreading the remains across a large area, wind and rain eroding away the remains, or even small insects and bacteria eating away at the bones. Ultimately, the remains need to be buried quickly, ushering them away from all these potential hazards.

Next, the remains must stay buried for thousands to millions of years. The main forces to avoid during this period are geological. The bones/fossils must survive all the geological forces that could potentially destroy them. These include mountain building, volcanoes, earthquakes, erosion, and landslides (to name only a few).

So is that it? Now that the bones have become fossils, they just wind up in the museum for us to enjoy, right? Not quite.

Now it is time for the remains to come to the surface. This step is really about timing. The fossils must be exposed on the surface and be discovered. Sounds easy enough right? Well, there is a catch. Not only do they need to be visible but they need to be visible to someone who recognizes them for what they are…fossils.

Visual representation of the fossilization process

Did dinosaurs recognize the fossils being exposed at their feet during their time walking the planet? Would you be able to recognize a fossil in the ground if you saw one? More to the point, would you be able to recognize a small part of an exposed fossil in the ground? Often, when fossils are discovered, only a fraction of the bone is exposed, while the rest is still buried under the surface. The fossils must be collected before the elements have had a chance to erode them away. How many fossils of ancient animals simply disappeared because they were exposed at the surface at the wrong time? How many fossils of shells, fish, or ancient reptiles did the dinosaurs destroy because they were walking on them?

Lastly, if you found the partially exposed fossil and recognized it for what it was, could you get it out of the ground intact? Someone could find the most beautiful or significant fossil ever discovered, but if they can’t get it out of the ground without it breaking into dozens or more pieces, they have only a useless pile of fragments-- not something that could go on display at a museum.

The final leg of the journey is entirely reliant on humans. The collected fossils now must travel safely back to a lab or museum, be removed from the remaining rock/dirt matrix, and still be in good enough shape to go into an exhibit. This often means not only the quality of the fossil must be good, but the fossil must also fit into the theme of the exhibit.

The dinosaur exhibit at the ND Heritage Center State Museum

The next time you walk through a fossil exhibit, I hope you remember that all the fossils you see on exhibit traveled this path. Do you ever think about what we are leaving future humans to discover about us?