Adventures in Archaeology Collections: Fort Berthold I

In the archaeology lab, we’ve recently had a lot of bags, boxes, and artifacts on the tables. These artifacts are from the site of the first Fort Berthold (32ML2, Fort Berthold I).

Fort Berthold I was a trading post located on the north side of Like-A-Fishhook Village (for more on Like-A-Fishhook, see previous posts at blog.statemuseum.nd.gov/blog/adventures-archaeology-collections-fishhook-village and blog.statemuseum.nd.gov/blog/adventures-archaeology-collections-fishhook-village-part-ii). This trading post was built around 1845 and was used until the early 1860s. This site, like the adjacent village of Like-A-Fishhook, was flooded by the Garrison Dam and was partially excavated by archaeologists in the 1950s as part of the River Basin Surveys. The site is now under Lake Sakakawea.

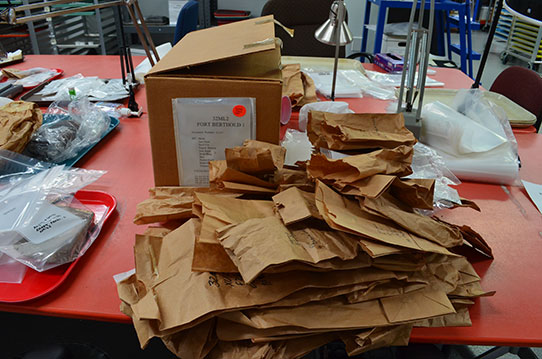

David Nix, one of our volunteers, has just finished photographing more than 1,700 artifacts from Fort Berthold I. We are now busy working with other volunteers (special thanks to Sandra, Mavis, Mary, and Gary) to transfer the artifacts from brown paper bags and bubble wrap into acid-free, archival storage materials.

Work in progress: sorting artifacts out of old non-archival storage materials

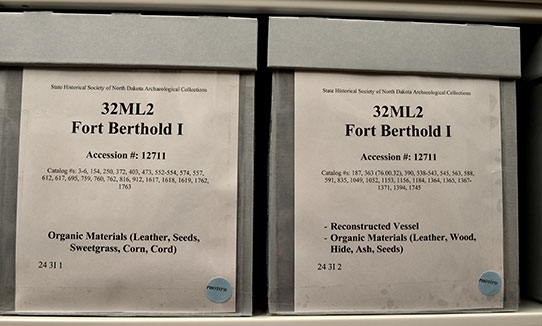

Repackaged boxes of artifacts

It is exciting to see some artifacts that are not common in the archaeology collections. North Dakota does not have a climate that preserves materials like plants, wood, or leather very well. But a few of those materials do survive in this collection!

There are shoes, shoes, and more shoes—as well as boots and overshoes—in parts, pieces, and even nearly complete examples. They come in many different shapes and sizes.

A small selection of the footwear from Fort Berthold I (12711.3, 1285, 1345-1346, 1427, 1745-1746, &1828, photos by David Nix– edited SHSND)

It is far more normal to see belt buckles by themselves in North Dakota’s archaeology collections than buckles with leather belts still attached.

Metal buckles are not uncommon in the archaeology collections, though not all are as fancy as this military buckle plate (12711.1541, photo by David Nix– edited SHSND)

A buckle with part of the leather belt still attached (12711.836, photo by David Nix– edited SHSND)

Two felt caps with decorative fringe are really interesting.

Felt caps (12711.251 & 761, photos by David Nix – edited SHSND)

A carefully braided fragment of delicate sweetgrass is also in the collection.

Braided sweetgrass (12711.612)

Here is part of a sewn birch bark object—you can see the holes where this piece was stitched.

Sewn birch bark (12711.1366, photo by David Nix– edited SHSND)

There are other canteen stoppers in the archaeology collections, but this is the first canteen stopper that I have seen with the cork still attached.

A canteen cork (12711.152, photo by David Nix– edited SHSND)

Less fragile, but not less interesting, is a flute made from a gun barrel. This is one of my favorite objects from Fort Berthold I. I wonder who made this and what kind of story is behind it. There is no mouth piece with it now. Did it ever have one? Was this a toy or a real instrument? If it was a real instrument, what did it sound like?

Gun barrel flute (12711.300)

Johnathan Campbell has been around the SHSND for around a quarter of a century. He has been the site supervisor for both the Former Governors’ Mansion, and Camp Hancock State Historic Sites for over a decade, and previous to that was the fossil preparator for the North Dakota State Fossil collection.

Johnathan Campbell has been around the SHSND for around a quarter of a century. He has been the site supervisor for both the Former Governors’ Mansion, and Camp Hancock State Historic Sites for over a decade, and previous to that was the fossil preparator for the North Dakota State Fossil collection.