Working Together

As a historian, I was very comfortable researching and writing topics for eighth grade North Dakota Studies curriculum North Dakota: People Living on the Land (ndstudies.gov/gr8). That is, I was comfortable until I faced Unit 1, which runs from the Paleozoic Era to A.D. 1200 I had much to learn about paleontology.

I turned to now-retired State Paleontologist John Hoganson. Hoganson’s articles and books are written for non-paleontologists. I interviewed John and read his publications. With his help, I developed a plan to bring paleontology into the eighth-grade curriculum.

While I was working on Unit 1, the Heritage Center expansion was underway. Another paleontologist, Becky Barnes, temporarily occupied a desk just a few feet from mine. I was fortunate to be within “hollering” distance of a paleontologist. I could have inquired in a loud voice, “Becky, how is Xiphactinus pronounced?”

The Xiphactinus was a predatory fish, 18 feet long, with immense fangs. Fossilized remains of a Xiphactinus that lived 85 to 65 million years ago were found in Cavalier County. 10.12.13.

But, I found that a trip to Becky’s desk offered other opportunities I had not imagined.

Becky is a paleontologist and an artist. She paints many images for the State Museum and paleontology publications. One day, I strolled over to her desk and found her working on an illustration of how sediment was laid down and how geological shifts and erosion had left the earth’s surface looking like what we see today. That illustration, “A Piece of Cake,” was modified and included in People Living on the Land.

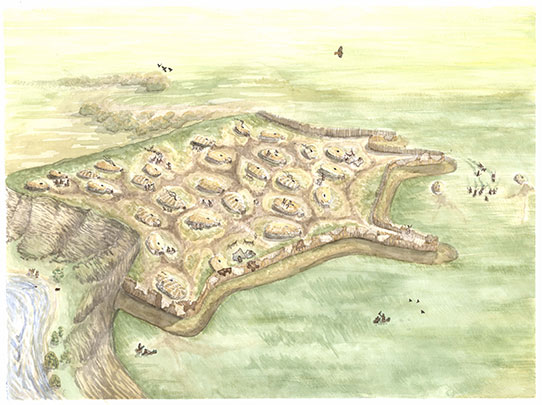

I worked with people in all divisions of the State Historical Society to develop a well-rounded curriculum. I turned to the Archaeology and Historic Preservation Division (AHP) for help with prehistory. I took an archaeology course once, so I wasn’t completely ignorant, but I depended on the division staff to direct me to pertinent research reports and photographs, guide me in the right direction, and answer my endless questions. State Archaeologist Fern Swenson encouraged me to use archaeological evidence to determine the ending date of Unit 1. Historians commonly use 1492 and the arrival of Columbus to divide prehistory from history. But Fern convinced me that A.D. 1200 is a better date for North Dakota Studies because that is when Menoken Village was occupied.

Menoken Village, located a few miles east of Bismarck on Apple Creek, was occupied around 1200 A.D. The palisade wall and the remains of earthlodges indicate that it was a permanent village.

The village is the earliest known permanent village site in North Dakota.

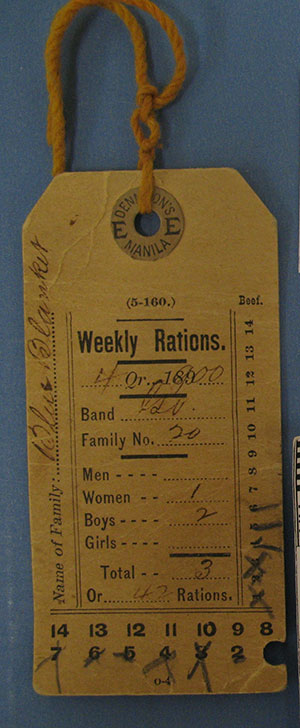

This ration ticket, for the last three months of 1900, indicates that Blue Blanket was the single mother of two boys. She received general rations (flour, salt, etc) and beef. Museum 381.2.

We wanted to include museum objects that could tell a story or illustrate a point. Jenny Yearous, Museum curator, helped me out one day when she brought out a bundle of ration tickets that had been used on the Fort Berthold Reservation. The ration tickets seemed a curiosity and a good illustration for reservation history. Further research indicated that the tickets told a profound story about the transition from a pre-reservation life of hunting and gardening to a life of poverty and dependence by 1900. Research in the federal Indian census produced more information and brought to life the families listed on the ration tickets.

With friendly advice from all divisions of the State Historical Society, the curriculum creditably covers 500 million years of history. By the way, Xiphactinus is pronounced zy FACT in us.