“PrehiStories”: How My Mosasaur Rhymes Inspired a Children’s Book

We have a family poem—yes, you read that right. When I was itty-bitty, my dad would come in to wake me up, chiming a poem. (I just learned this poem was a somewhat altered version of Robert Louis Stevenson’s “Time to Rise.”) Dad’s take went like this:

Birdie with a yellow bill,

Hopped upon my window sill,

Cocked his shining little head,

“Get up you sleepy head!”

Over the years, my family added new and different verses to the poem, depending on the situation. For instance, during one winter cold snap, where many days fell below zero degrees, it went like this:

Birdie with a yellow bill,

Frozen to my window sill,

Can’t cock his shining little head,

Oh my gosh, I think he’s dead!

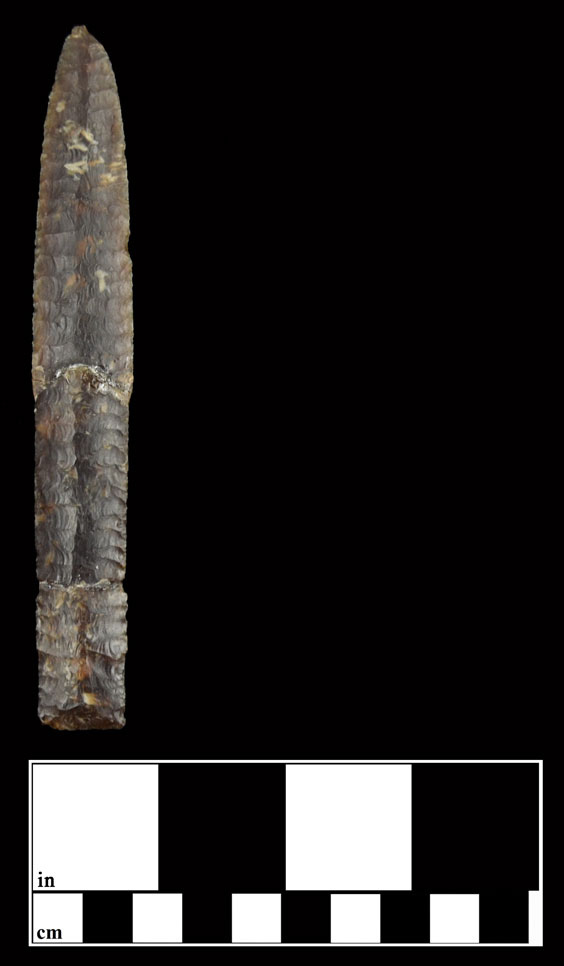

Thus rhyming, verse, and alliteration were very important methods of communication in my family—and the habit has stuck with me over the years. During the summer of 2018, while conducting the Pembina Gorge Fossil Dig, inspiration struck. We had been excavating a partial skeleton of a mosasaur (a type of marine reptile you can view on display at the North Dakota Heritage Center & State Museum) and were taking a dinner break. Sitting around the table with friends and colleagues, I began coming up with mosasaur rhymes. I struck on a fun rhythm—a couplet with 10 beats per measure.

Sit all around, and I’ll tell you a tale:

Meet our friend Mosasaur, big as a whale!

Well, that was a fun intro! I wondered how much I could write about mosasaurs before running out of ideas and giving up? The evening stretched on, and I bounced ideas off of Clint Boyd, senior paleontologist with the North Dakota Geological Survey, and fossil preparator Trissa Ford, who were also on the dig with me. By the end, we had figured out most of a book filled with an array of mosasaur facts. The mosasaur was not a dinosaur. It lived in the water. Some were big; some were small. They had different diets, had live births, and breathed air. The list kept going, and it was fun to read, so my bosses with the North Dakota Geological Survey decided I should make a children’s book, illustrate it in a fun way, make it relatable to kids, and include a few extra fact bubbles to fill in some of the complex ideas.

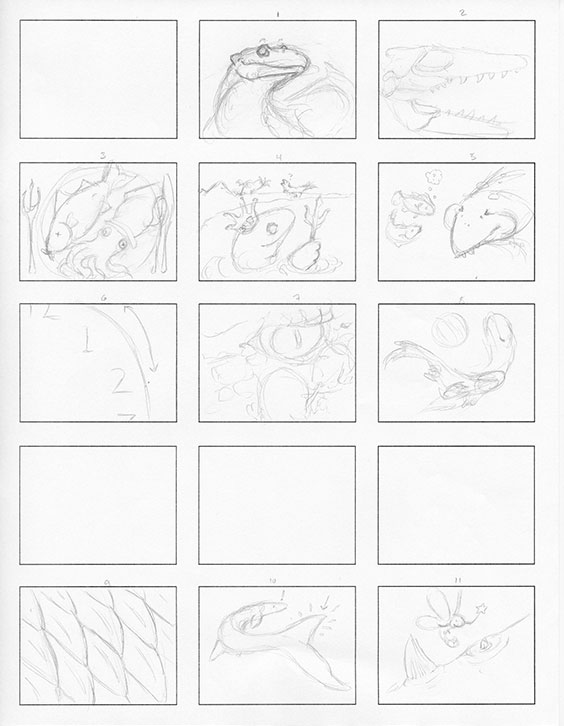

This is the start of my storyboard layout, where I played around with design and action.

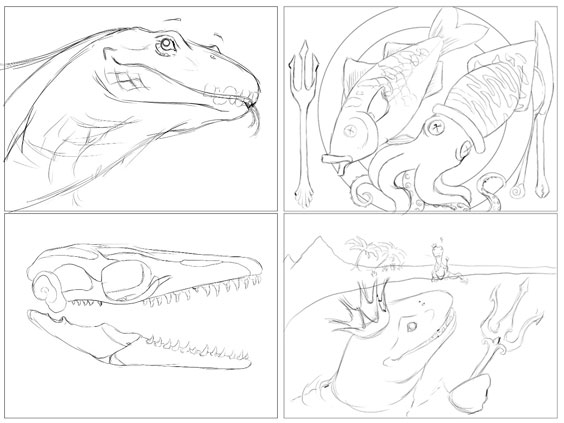

These are more refined storyboard sketches, before inking and watercolors have been added.

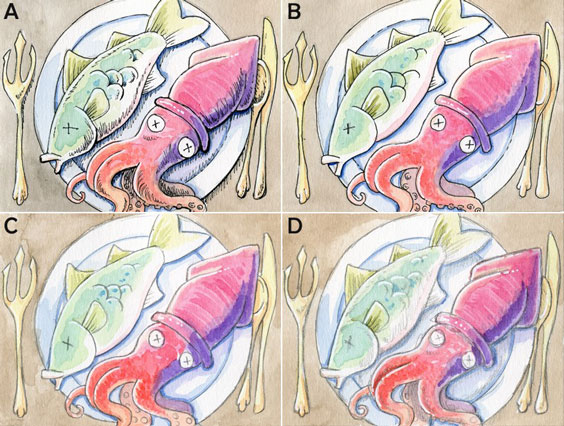

Before the storyboard got too far, I needed to figure out the feel for the book. I took a page I knew I wanted to use, drew it up four times, and experimented with pencils, ink, shading, and color.

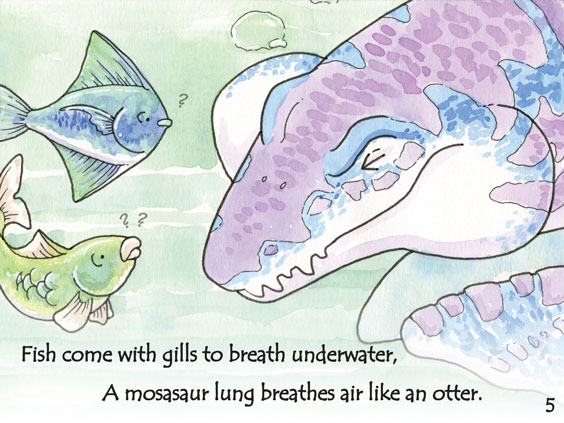

After sketching some test runs, I settled on an ink-and-watercolor style. Not too much detail, but not too little either. All were done with bright colors. The next few weeks were spent painting, painting, painting! My storyboard was printed and taped to my desk—as I finished one page, the storyboard would get a nice big X over the image. It was very satisfying to see the to-do list shrink and the ready-to-scan pile grow.

A fully painted page.

Once everything was painted and scanned, I had to put the images, text, and facts together in the computer. To be honest, this fiddling, placing, and tweaking probably took more time than the writing and painting. However, I am pleased with the result. Coming up with a title for the project was also fun. Since it’s a prehistoric setting about a mosasaur, and “-storic” sounds pretty close to “story,” what if we made it a “PrehiStory”? But wait! What if we make up other stories in the future? Then it could be: “PrehiStories”!

And finally, here is the painted page with text overlay.

Thus was born, “PrehiStories: Mosasaur.” If you’d like to pick up your own copy, they’re available at the North Dakota Heritage Center & State Museum gift shop.

* * *

Here is a bonus bird verse from my childhood. My dad had gone boating, and while hopping out of the craft, injured his arm quite badly, which inspired the following rhyme:

Birdie with a yellow beak,

Caught his wing upon a cleat

Turned his head to take a peek,

“Oh my gosh I’ve sprung a leak!”