Data May Be King, But Relationships Fuel State Historical Society Mission

These days, much attention is paid to data. In fact, those of us working in the history field are continually asked: “What does the data say?” And let’s face it, we live in a world where data rules. Big technology companies, social media, and the retail world are almost single-mindedly driven by data. More data means more money, and everyone tells us so. Someone is paying big money for your data. Important as data may be, I think it is wise to remind ourselves that organizations such as the State Historical Society of North Dakota are powered by an old-fashioned fuel called relationships. In fact, we thrive on them. It is my hope that every day we build at least one new relationship.

One of our most important partnerships is with the State Historical Society of North Dakota Foundation. The Foundation raises nongovernmental funding for us. The Foundation team is made up of a dedicated group of staff and board members from all over North Dakota. When people with financial resources want to support our work, the Foundation is the mechanism through which those funds are leveraged for our mission. The Foundation has been with us on the big projects such as the 2014 expansion of the North Dakota Heritage Center & State Museum, but also on the smaller projects. The Foundation provides valuable assistance in volunteer recognition and appreciation events. It provides funding for staff development grants and helps our staff share their knowledge with people across North Dakota.

Another important state partner is the office of North Dakota Tourism. This partnership is very important to the State Historical Society because they assist with marketing our museums and historic sites. We are currently working with North Dakota Tourism to co-brand a few of our interpretive centers as state visitor centers. North Dakota Tourism does not currently have official visitor centers. The State Historical Society has interpretive centers on major transportation routes in North Dakota. We feel that by partnering with the state tourism office we can deepen existing relationships and build new ones. Our first visitor center pilot project will be at the Chateau de Morès State Historic Site in Medora, opening in April.

Until the late 1960s, the State Historical Society and North Dakota Parks and Recreation were one agency. Since then, we have continued to partner with their agency on a variety of projects. Recently, for instance, I have been part of a team that consists of our historic site managers and new media specialists working with state Parks and Recreation counterparts to develop a program that will encourage new audiences to explore North Dakota’s state parks and state historic sites. We also work closely with their agency on archaeology and historic preservation projects.

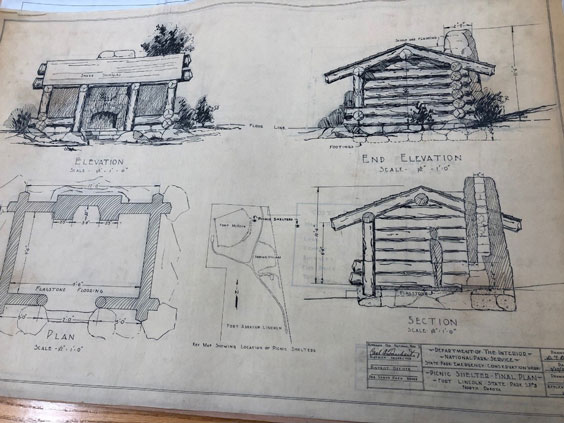

Drawings of a Fort Abraham Lincoln State Park picnic shelter held by our agency are helping the North Dakota Parks and Recreation Department plan for the reconstruction of the shelter, which burned this past fall. State Series 30249 Historical Society. State Parks, Fort Abraham Lincoln State Park Records

At the ND Heritage Center & State Museum, we also share our physical space with paleontologists from the North Dakota Geological Survey. Because the missions of the two agencies are parallel, we collaborate on some fossil projects in the Adaptation Gallery: Geologic Time. It’s a win for all, as visitors to the State Museum can take in millions of years of history in a single stop. And data confirms that people love dinosaurs!

In a partnership with North Dakota Geological Survey, their paleontologists are working with our staff to update a State Museum exhibit about Dakota, a rare fossilized Edmontosaurus in our collection. Here, one of Dakota’s arms is fitted into a mount for future exhibition.

No conversation would be complete for us at the State Historical Society if we didn’t mention our friends groups that support the work at our historic sites across the state. By my count, we have 10 official friends groups supporting our work at Fort Abercrombie, Fort Buford, Ronald Reagan Minuteman Missile Site, Chateau de Morès, Former Governors’ Mansion, Camp Hancock, Whitestone Hill, Stutsman County Courthouse, Fort Totten, and Welk Homestead. If you were to add up all the volunteer work and financial contributions of these groups over the years, the totals would be staggering. The work these groups help us achieve is truly remarkable.

Friends of Fort Union and Fort Buford were instrumental in providing funding for the barracks exhibit at Fort Buford State Historic Site.

One of our friends groups, the Society for the Preservation of the Former Governors’ Mansion, raised about $40,000 for a new roof at the state historic site. The group has been helping support the upkeep of the mansion at 320 E. Ave. B in Bismarck for decades.

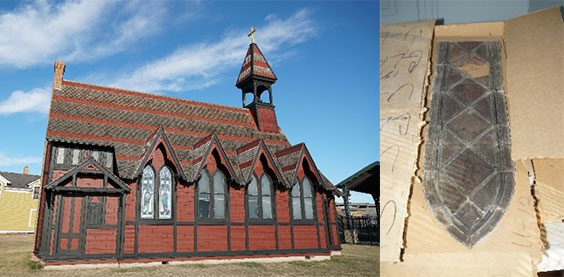

Our newest friends group, the Bismarck Historical Society, is fundraising to help us restore the stained glass windows at Camp Hancock State Historic Site’s Bread of Life Church.

Finally, we must not forget the relationships that we have with our elected officials. The secretary of state and state treasurer serve on the State Historical Board. We also work with the governor’s office and staff on various programs and projects. With the North Dakota Legislative Assembly currently in session, we are reminded of our close relationships with our legislators.

Members of the state House Appropriations Committee, Reps. Mike Nathe, David Monson, and Mike Schatz, and staffers try out new auditorium chairs at the ND Heritage Center & State Museum. Support for the auditorium remodel came from both state funds and the State Historical Society of North Dakota Foundation.

Don’t get me wrong, data can provide us with information about our visitors, how much they make, where they live, how many children they have, how long they have been married, and if they are likely to visit us again. It is good to have data. One thing the data tells me is that that we need to pay close attention to our relationships—we need to nurture the ones we have and look for new ones. All of them are important, and all of them are beneficial.