Red River Ox Cart Trails—Our Early Highways

Mention ox cart trails, and many of us visualize deeply rutted paths traveled on by squeaky-wheeled carts. But just as the Pembina Highway in Manitoba and Interstates 29 and 94 in North Dakota and Minnesota are important links in international trade between Winnipeg and the Twin Cities today, the Red River trails of the 1800s were equally important to 19th century trade.

As site supervisor of the Pembina State Museum and Gingras Trading Post State Historic Site, a great deal of the history we present revolves around the Métis, the fur trade, and the Red River carts (the centerpiece of the museum—see photo below). The history of this transportation system created a lot of questions and field trips for me.

Prior to 1800, almost all commerce in the frontier was accomplished by canoe. The Hudson’s Bay Company hauled furs north—including a crossing of Lake Winnipeg—eventually ending up at posts on the shores of Hudson’s Bay where ships waited to transport the furs to Europe. The Northwest Company carried their furs east through the Great Lakes, with a lot of river and lake hopping via portages, until reaching Montreal and the ships bound for the hungry European markets. But travel by canoe was difficult and dangerous.

Credited with using the first carts in the Red River region was Northwest trader Alexander Henry from his post at Pembina. They were relatively small and had solid wheels.

An example of an early Red River cart as would have been used by Alexander Henry

In the early days, the primary route of travel closely hugged the banks of the Red and Minnesota rivers. Due to the nature of the soil in the Red River Valley, these horse-drawn carts could only be used during dry periods, with mud being a major limiting factor. However, cart design and trail location would quickly evolve to meet the challenges of overland travel.

Métis ingenuity created larger carts able to haul up to 1,000 pounds that could be pulled by oxen. Wheel diameter was increased by several feet and were spoked rather than solid. The wheels were dished, or curved inward, to add stability and better handling. By 1830, the more well-known carts were in use and replaced the canoe as the primary means of shipping goods between Winnipeg and St. Paul.

A traditional Red River ox cart. This example, housed in the Pembina State Museum, was built in the 1920s by Louis Allery in the traditional style of the Métis.

While the specifics of the carts themselves are interesting, the selection for trail routes fascinated me. Along with the more versatile carts came new trails. Although the river trails were still used during dry times, the primary trails were moved out of the Red River Valley onto the ancient beach ridges formed by glacial Lake Agassiz. Aptly called the Ridge Trail or West Plains Trail, the soil was much sandier and well-drained, making mud less of a factor. In Minnesota, the trail shifted from following the Minnesota River to a much more direct cross-country route called the East Plains Trail. These remained the principle routes until an unfortunate incident.

Map of the primary trails

In a case of mistaken identity, a group of Métis buffalo hunters attacked a group of young Dakota hunters, with several Dakota being killed. Seeking retribution, the Dakota began patrolling the Plains Trails. In order to avoid a confrontation, the next train of ox carts leaving St. Paul turned north and cut a trail through the forests of Minnesota, which was Ojibway territory, a people friendly to the Métis. Cutting the trail was slow and arduous, but the resulting Woods Trail was used on and off for years depending on the political situation between the Métis and Dakota.

Travel by ox cart was slow, but efficient. Made entirely of wood and leather, there was no need for a blacksmith for on-the-trail repairs. Able to move 15 to 20 miles a day, the course of the trails was carefully selected so that at the end of the day there was always a supply of wood for repairs and cooking fires, and water for the animals. Routes were also chosen based on locations where crossing streams and rivers was easier.

By the 1860s, several thousand carts were making the trip between Winnipeg, Pembina, St. Paul, and the many fledgling settlements along the way. The primary trails saw improvements done by both stagecoach companies and the military, both of which heavily used the trails. Even the Hudson’s Bay Company saw the practicality of overland travel and negotiated trade agreements with the U.S. government to ship their goods via the trails.

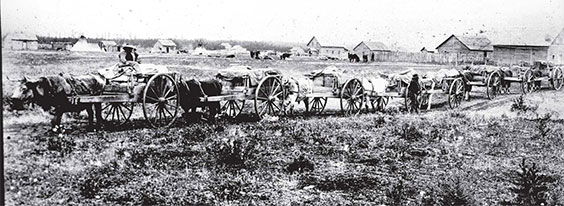

Red River ox cart train

The thriving economy created by the Métis in the Red River region, centered around the bison trade and their carts, was short-lived, however. Competition existed with steamboats but was erratic due to the normal fluctuations in Red River water levels. The arrival of the railroad at Breckinridge in 1871 and Moorhead a year later, combined with dramatically declining bison numbers, forced the Métis bison hunters north and west, leaving a few ruts in the landscape as the only tangible reminder of a prosperous era.

Remnants of ox cart ruts along the old Red River trail

Although most of the cart trails are gone, having been cultivated for decades, some remnants still survive. Finding them can be a bit tricky, but with a little hunting they can be discovered. One spot is at Icelandic State Park near Cavalier, although locating the trails there is a challenge and requires staff assistance. Several other trail pieces have been recognized on the National Register of Historic Places. These include various sites in the Ridge Trail Historic District in Pembina and Walsh counties and the Dease-Martineau House, Trading Post and Oxcart Trail Segments near Leroy, North Dakota, although permission is needed to enter. Contact the Pembina County Historic Preservation Commission at 701.265.4561 or pembinaclg@nd.gov for more information. An easily accessible place to view a trail is in Crow Wing State Park near Brainerd, Minnesota. An incredible source for more information is the book The Red River Trails: Ox Cart Routes between St. Paul and the Selkirk Settlement by Rhoda R. Gilman, Carolyn Gilman, and Deborah M. Stultz.