And the Bride Wore…

Former Governor Arthur and First Lady Grace Link at their wedding in 1939. SHSND SA 10943-76

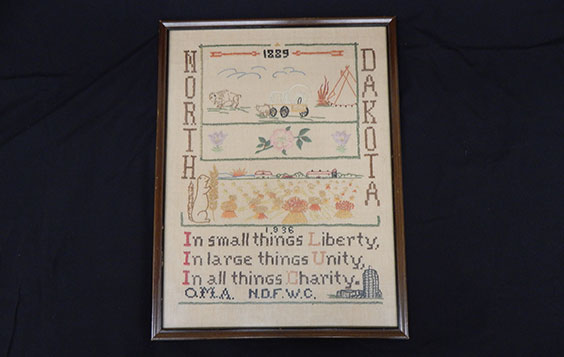

Fashion & Function: North Dakota Style, the upcoming exhibition at the North Dakota Heritage Center & State Museum, includes 19 thematic sections ranging from decorative and symbolic feather usage to graduation gowns. One section—dubbed “The Wedding March”—focuses on bridal traditions utilizing a selection of garments, photographs, and accessories. And while bridal white features prominently in the layout, it isn’t the exclusive color.

Drawn from the State Historical Society’s objects and photographic collections, the display captures a wide range of garments worn by North Dakota brides, including an afternoon suit, an evening dress, and an ensemble hand-crocheted by the bride’s grandmother over a three-month period.

Also included are two folk ensembles worn by Norwegian and Icelandic brides in the mid-19th century. The colorful Norwegian bunad includes elaborate embroidery worked with glass beads, while the Icelandic Skautbúningur features a national folk style introduced just prior to its wearing in 1861.

Wedding portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Dick Ramsey, Fort Yates, circa 1908. The bride wears a fashionable, flounced, white cotton batiste lingerie dress with a dotted Swiss motif, a floral headdress, and silk tulle veil. SHSND SA 1952-2037

The most formal gown in the grouping is also the “history mystery” within the exhibition, as it appears incomplete. The ivory wool flannel and silk brocade gown (SHSND 13405) was worn by Jennie Martha Kelley at her marriage to Oscar St. Clair Chenery, in Jamestown, during the late territorial period. The gown stylistically falls within the second bustle period of the 19th century.

Bodice and detail of the Kelley wedding gown, 1886. SHSND 13405

Beginning in the late 1860s the fullness of the period’s bell-shaped skirts began to shift—with the mass moving to the back—often accented with swaged overskirts and flared peplums. This silhouette collapsed in the late 1870s with the introduction of fitted princess-line gowns featuring long trailing fishtail trains. Then, in the 1880s, the bustle reappeared as a very prominent feature extending much like a wide shelf from the base of the wearer’s back.

The period was distinctive for the profuse use of upholstery trims, embroidery, draped swags, and knife-pleated ruffles, all accenting the mass of the bustle. It was the age of conspicuous consumption. Bustles (politely termed tournures) were supported by spring wire, horsehair, and hinged steel hoop understructures of a scale that made it impossible to sit back in a chair, forcing fashionable women to perch sideways when they sat. Ladies chairs were designed without arms to accommodate their full skirts.

The Kelley wedding gown dates to 1886. Its “history mystery” is that the distinctive bustled train is missing. The skirt has been modified yet retains a removable half-moon-shaped dust ruffle indicating the fullness of the original bustle and chapel-length train. The dust ruffle would have protected the underside of the train as it dragged across floors and the ground.

Two lace-edged silk brocade swags positioned over the skirt’s hips—known as a polonaise (in the Polish style)—indicate they led to an incomplete back arrangement that no doubt incorporated both a third swag (completing the polonaise), and a cascade of both silk brocade and lace forming the train. The bustle must have been made as a separate component attached to the back waistline of the skirt.

Another feature of the wedding gown is its rather deep neckline. As it appears, the bride would have had reason to blush as she would have gone down the aisle virtually bare breasted! The neckline’s deep cut and the presence of narrow lapels and lace ruffles indicate it was filled with a chemisette—much like a dickey—providing a more modest secondary inner neckline, probably fashioned of gathered silk tulle matching the dress trim.

Do you know the difference between a bodice and a blouse? A blouse—while it can be tailored—is unstructured. A bodice has a fitted inner lining often including boning and occasionally padding. The steel boning in the Kelley wedding bodice was intended to maintain a smooth silhouette. A separate corset would have been worn as part of the underwear to support the bride’s figure.

Fashion & Function: North Dakota Style will appear in the Governors Gallery at the North Dakota Heritage Center & State Museum in 2021.