How Did You Even Find That?

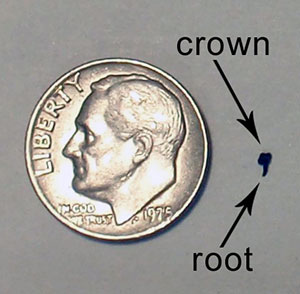

This is a very small mammal tooth next to a US dime for scale.

The search for microfossils is sometimes a very unrewarding task. I have collected, washed, and scoured through, quite literally, tons of rock looking for a single mammal tooth. But however tedious and arduous the task of looking for microfossils is, the rewards greatly outweigh the time spent looking. Microfossils are, as you may have guessed, very small fossils. These small fossils can be anything from microscopic animals that lived in water environments to very small bone fragments to very, very small teeth and everything in between. In this case I am referring to very small mammal teeth. These teeth are so small they can be glued on the head of a pin.

The recovery process of these teeth begins with collecting rock. However, paleontologists don’t just randomly stick a shovel in the ground and hope to hit pay dirt. Sites used to study microfossils are chosen very carefully. These sites, called microsites, are usually places where other fossils are already weathering out at the surface. Small fossils, easily visible with the naked eye, are usually common, and the fossils tend to be concentrated within a definable, thin horizon.

This is an example of a thin fossiliferous horizon. The black specks in the overturned chunk are fish scales.

A volunteer in the Johnsrud Paleontology Lab looking for microfossils.

This horizon is then collected by hand or by shovel and brought back to the laboratory. That collected rock is then subjected to a process called screen washing. The collected dirt is washed through one or sometimes two sets of screen, the smallest screen usually smaller than the screen on your windows and doors at home. What remains on the screens after washing is dried and then systematically “picked”- under a microscope where microfossils are collected from the remaining dirt and rock.

The most common fossils that come out of this concentrate are usually fish bones and teeth. Rarely though, a mammal tooth will be found. It is these rare mammal teeth that can potentially tell us the most about one particular site. From being able to potentially restrict the age of the site to within a few million years or to give us greater detail about the paleoenvironment, fossil mammals play an important role in paleontology.