Digging for Fossils, Searching for Answers

How far would you go to get something you want or need? Would you make a special trip up a flight of stairs in your house to get new batteries for the remote? Or would you wait until you had to go up for another reason? How about two flights? What if I took away the stairs, and you had to walk up a hill? How far would you go then? Ten feet up? Twenty feet? Thirty feet? What if your prize at the top of the hill wasn’t something you could easily replace from a drawer in your home but instead was the key to a box? A box that contained the answer to a question you’ve asked yourself for more than a decade. Now for the final wrinkle. What if I told you that the key you’re searching for is likely at the top of that 30-foot high hill, but I can’t guarantee it’s there, or if it is there that you’ll even find it. Is your answer still the same as it was at the beginning?

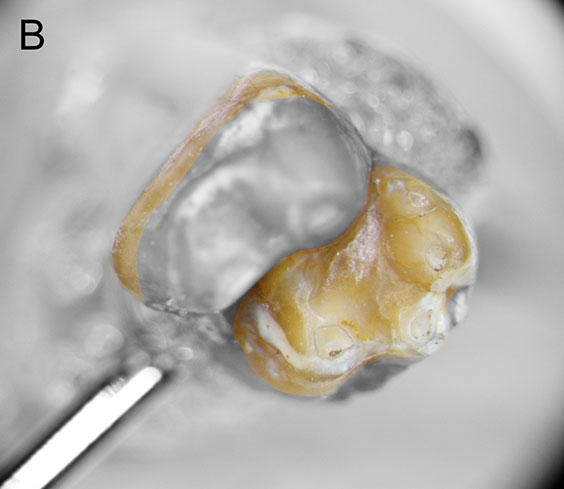

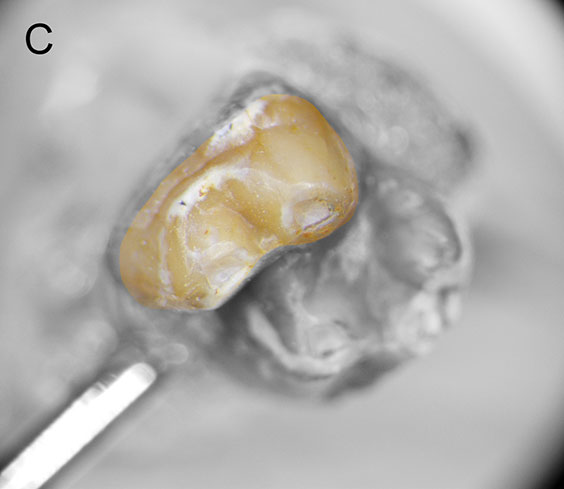

I recently found myself in a situation very similar to this. In the hopes of answering a question that I’ve asked myself for 13 years, I had to collect a lot of rock from a very tall butte in North Dakota. So a small group of us went to a site in the southwest corner of the state. We had to collect a lot of rock because the fossil animals we were looking for are very small, rare, and hard to find. As a result of the small size and scarcity, the bigger the sample size we collected, the more likely we will find what we’re looking for. After all the work was done, we had collected more than 800 pounds of rock from the top of that butte. The rock then had to be carried by hand in buckets down the butte and across the prairie. There is a high probability that the reward will be worth the effort. Maybe I will finally answer that question that has been burning in my mind for more than a decade. If not, I’ll try again and again until I’ve answered my question.

Our quest involved hauling roughly 800 pounds of rock from the collection site to a waiting truck.

This is the quandary faced by scientists all over the world. But in my opinion, not knowing what you’ll find or when you’ll find it just makes the endeavor more exciting. At times, the work paleontologists do can be hot, dirty, and tiring. Nevertheless, for me, the discovery part of science is both fun and rewarding — answering the questions that no one has answered (or even thought to ask) and finding something new that no one has discovered. That is what keeps me coming back for more, and I bet a lot of you feel the same way.

Could the answer to my burning question lie inside one of these buckets?

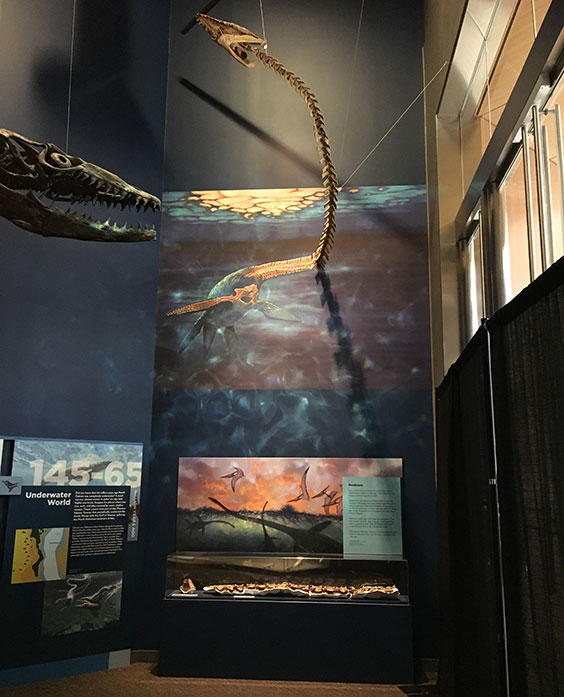

If you want to join me on the quest for answers, come along on one of our public fossil digs. We hold them every summer. Please keep in mind that while not every dig we offer requires a lot of physical strength, all of them require patience. The fossils we work with are fragile and need a certain amount of care to remove them intact, but you will learn how! Follow us on social media to find out when registration will start. We are on all the major platforms (Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram), just search for @NDGSpaleo. I hope to see you next summer!