Adventures in Archaeology Collections: Summer Trip to the Beach

It’s still summer, and it isn’t too late to visit the beach! Maybe even the ocean? With that in mind, here are a few artifacts from the archaeology collections that remind me of a trip to the beach.

Here in North Dakota, you might expect prairie schooners (covered wagons). Actual schooner ships, not so much. But this pocket watch case from Fort Abraham Lincoln has a schooner on it.

Part of a pocket watch case from Fort Abraham Lincoln (32MO141) (86.226.6041)

This is not the only nautical-themed item from Fort Abraham Lincoln. A pair of suspender buckles and a rivet feature an anchor motif.

Fragments of suspender buckles and a rivet, all from Fort Abraham Lincoln (32MO141) (86.226.16103, 16540, 17362)

If a fish story is more to your taste, how about this pipe fragment?

Two views of the same smoking pipe from Fort Abraham Lincoln (32MO141) (86.226.16950)

One of the volunteers unwrapped this while helping us rehouse an older collection into archival materials. There was originally a cherub figure or child riding the fish — you can see part of a leg and a tiny hand on one side of the fish. And that is by no means the only fish pipe in North Dakota’s archaeology collections. If you ever visit the North Dakota Heritage Center & State Museum, you can visit this clay fish pipe in the Innovation Gallery. It comes from Ransom County.

A fish-shaped smoking pipe from Ransom County, ND. (83.402.9)

Have you ever found a shell at the ocean? How about in the middle of a field? A family in Stutsman County found this large conch shell while working on their farm.

Two views of a conch shell from the archaeology shell comparative collection. This large seashell was found in Stutsman County! (A&HP shell comparative collection)

Many thanks to the Hochhalters for their thoughtful donation.

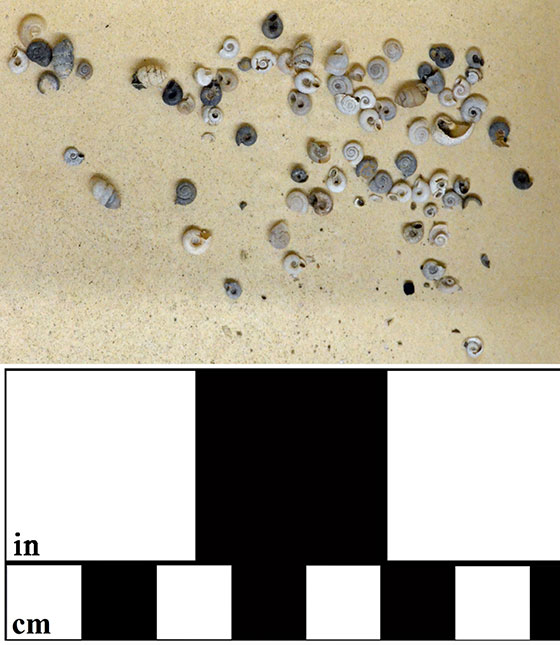

While our former chief archaeologist and in-house malacologist (someone who studies shell) Paul Picha determined the shell probably isn’t very old, the family kindly donated it so it can be used in the shell comparative collection. Seashells are found at North Dakota sites, so it is helpful to have complete or nearly complete examples for comparison. The site artifacts all came from faraway seashores to North Dakota by Native travel and trade networks. Examples of seashell artifacts found in North Dakota include this ornament made from a columella (central pillar) of a large shell, and these abalone shell pendants.

Left: An ornament made from the central column of a large seashell — the shell has been cut, shaped, polished, and a hole (now broken) was drilled near the top (81.40.2)

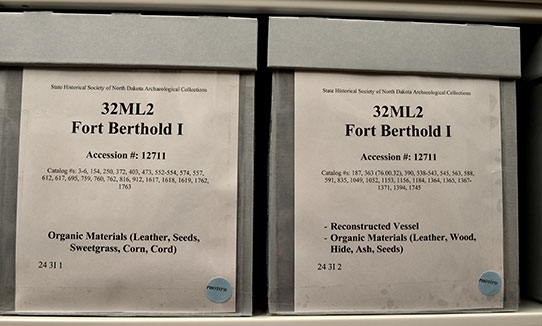

Right: Three abalone shell pendants; the one on the left is from Fort Clark (32ME2), the one in the middle and on the right are both from Like-A-Fishhook Village (32ML2) (4518, 12003.2105, 12003.1361)

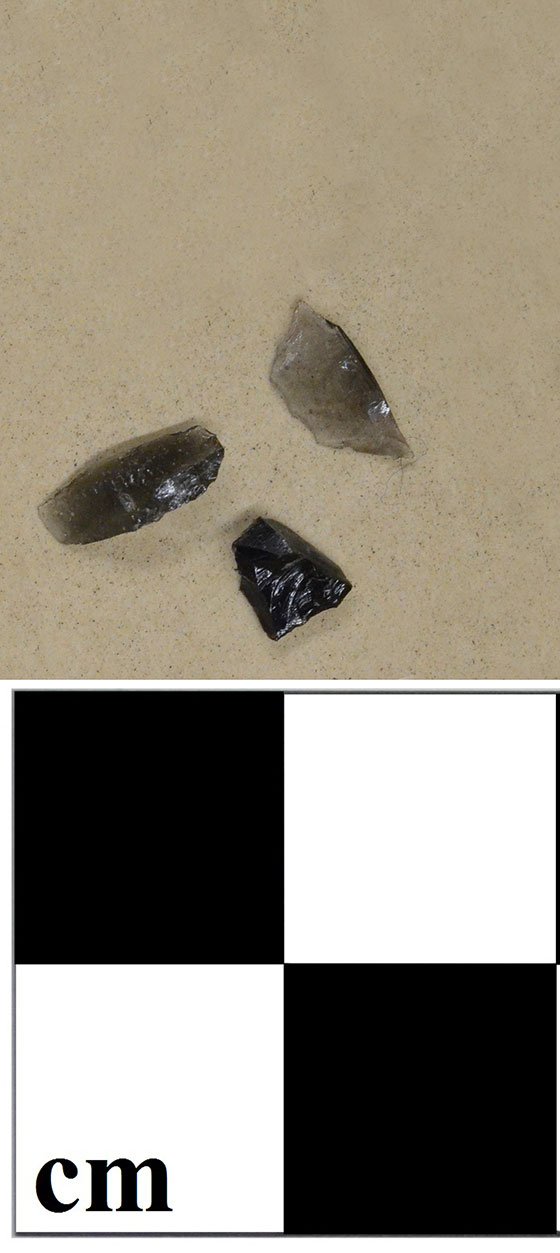

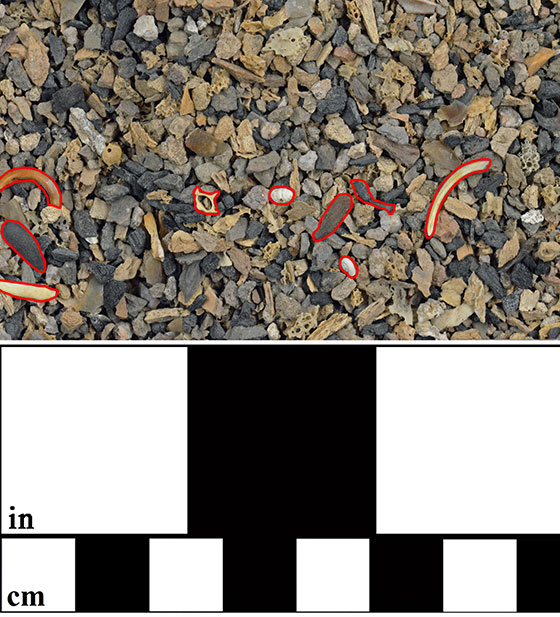

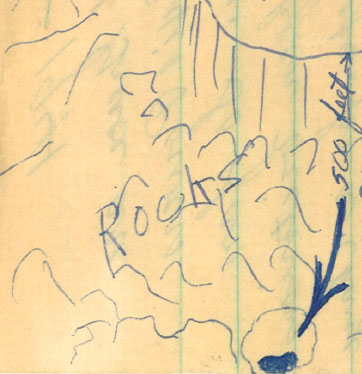

Let’s end this blog entry with a photo of a beach — the Beach cache, that is. This amazing group of tools and tool materials was placed in a storage pit (called a cache) by Paleoindian people. The cache was discovered in the 1970s near what is now Beach, North Dakota.

Some of the bifaces from the Beach cache. There are several types of rock in the cache; the tools in this photo are made from Sentinel Butte flint. (2007.75.5, 2007.75.17, 2007.75.22, 2007.75.13, photos by David Nix)