Hiding in Plain View at North Dakota’s State Historic Sites: A 19th-century Design Fad’s Signature Style

During my first months as an historic sites manager, I was struck by some similarities in furniture and decor at many of our 19th-century sites. Examples include geometric or flattened floral patterns, folksy surface carvings, fluted parallel trim lines ending with rosettes, and daisy and sunburst motifs. At some of these state historic sites, just a couple of pieces of furniture had the look, while at others it permeated nearly the entire building. Then I also noticed these features in dozens of furniture pieces in the agency’s artifact collection. These features are representative of Eastlake style, a 19th-century design craze inspired by Charles Locke Eastlake’s 1868 book, “Hints on Household Taste in Furniture, Upholstery, and Other Details.”

Original silverware and reproduction wallpaper at the Chateau de Morès State Historic Site represent an American take on Eastlake style. Note the abstract and geometric patterns, as well as the medieval and Asian influences.

I’ve been a fan of architecture and interior design since childhood. Some of my earliest memories are of different buildings and how their designs shaped my emotions. So it should come as no surprise that I read “Hints on Household Taste” when I was a teenager. It’s stuck with me ever since.

American Eastlake style is known for its sumptuous hardware. The Former Governors’ Mansion State Historic Site in Bismarck is blessed with many examples.

Eventually I realized there’s a simple reason why Eastlake style is so common at our sites and in our collections: Its popularity coincided with the completion of the Northern Pacific Railway. In the 1880s, this railway would bring in thousands of new settlers and facilitate the shipment of furniture, fancy-cut millwork, hardware, and wallpaper throughout Dakota Territory. Although Eastlake, the man, was British, his book had been a huge hit in the United States, going through six editions by 1881, and American manufacturers copied the look with gusto. Since the 1880s, most Eastlake influences in North Dakota have been torn down, thrown away, or remodeled, but numerous traces survive at state historic sites, including at the Chateau de Morès (1883), Stutsman County Courthouse (1883), Former Governors’ Mansion (1884), and Bread of Life Church (1880-1885) at Camp Hancock.

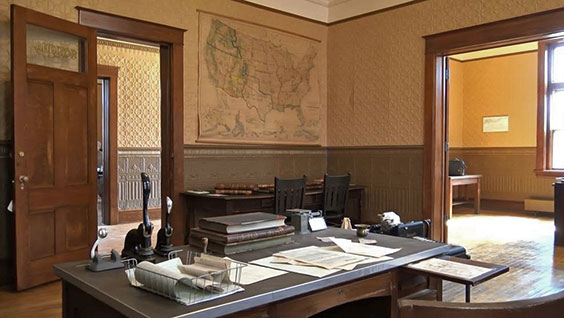

The 1883 Stutsman County Courthouse in Jamestown preserves several Eastlake features, including the original courtroom bar. Its turned spindles, parallel grooves along the upper railing, and chamfered (beveled) corners are typical of the Eastlake movement. As with most American Eastlake woodwork, the abstract star patterns were probably not handcarved but stamped with a press.

Eastlake had grabbed Victorians’ attention with a bold claim: Their homes were filled with lies. Gilding, metal plating, surface veneers, as well as imitation wood and stone made their possessions look more expensive than they really were. Likewise, new machines tried to make mass-produced objects appear as if they had been handcarved, embroidered, woven, painted, or forged by artisans. People had grown so accustomed to trickery, he wrote, that they no longer questioned why a chair should have lion’s paws as if it could scurry away, or why rugs should be covered in lifelike flowers when we would never step on flowers in real life. He believed that living among dishonest design was stressful and uneasy.

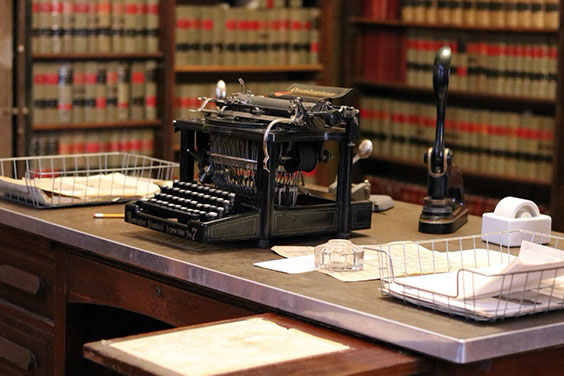

The judge’s bench, rear center, and the desks in the front left and right are other textbook examples of American Eastlake style preserved in the 1883 Stutsman County Courthouse. The court recorder’s desk, front center, with its neoclassical pilasters is a different style and was probably purchased years later.

To illustrate his point, Eastlake identified the wooden mop bucket as a truly beautiful object. Though simple, its design honesty reflected how it was made and what it was used for. Eastlake was so dedicated to the honesty of materials that he believed wood shouldn’t even be stained a different color. His philosophy significantly influenced modernist design during the 20th century.

At left, a circa 1890 photograph of the parlor of what would become the Former Governors’ Mansion State Historic Site reflects an eclectic blend of Eastlake, Asian, Empire, and Rococo styles. The flat floral design of the original wallpaper specimen, right, had a lustrous metallic gold background but is now faded and barely visible. We hope to recreate its original appearance the next time we wallpaper the room. SHSND SA 00071-00040

Today, Charles Eastlake is remembered, along with art critic John Ruskin and designer William Morris, as a leader of the Arts and Crafts movement, which celebrated old-fashioned handcraftsmanship during an age of increasing machine production. The movement valued workers taking pride in objects they made themselves, with any resulting flaws in their creations reflecting the real human effort that had produced the objects. Much to Eastlake’s chagrin, however, American manufacturers who used his name weren’t interested in handcraftsmanship. They simply used industrial machinery to copy the looks seen in his book. Hence, the Eastlake furnishings you’ll see at our sites include plenty of machine-stamped “carving,” gold foil, wood stain, metal plating, and imitation materials.

The Bread of Life Church at Camp Hancock State Historic Site blends Gothic Revival, Stick, and Eastlake styles—all of which drew inspiration from the Middle Ages. Note the chamfered corners on the pillars, in this instance highlighted with silver paint. Only a portion of the original silk-screened leaded glass windows survived intact like the beautiful detail seen here, but the Bismarck Historical Society is currently fundraising to restore the rest.

It’s fitting that Eastlake style is evident in so many of Dakota Territory’s earliest buildings. After all, the territory represented a sort of tension between individual work and industrial might—the hand labor of homesteaders and the power of railroads and grain mills on which they depended. Next time you visit, I hope these insights will help you enjoy our sites on a new level. You never know what you’ll find hiding in plain sight!