A Year of Collections Surprises

Collections work inevitably involves surprises – just ask any curator. Looking for an elk antler flesher to use in an exhibit? Surprise! There are some decorated stone gaming pieces in the same box that you didn’t know you had.

Stone gaming pieces (10199)

About to start your third tedious hour sorting through tiny bits of residue from a 16th century village trash midden? Wait! There is the tiny, polished tip of a bone needle!

Conducting a federal random audit of your collections? The surprise here is that the way we stored fragile shell in plastic bags many years ago (instead of vials) did not work out very well (okay, so not every collections surprise is a good one…). Surprises can come with a lot of challenges sometimes, but most of the time they make for an especially exciting day at work.

2014 was a particularly good one for surprises in the archaeology collections. Here are just a few of my favorites…

A Hidden Archive

Doug Wurtz (one of our volunteers) is doing research on Fort Rice, a US military fort built in 1864. As he has become more interested in the fort and the men who served there, he has expertly spun us into what we affectionately call his “Fort Rice web.” Without our realizing it, many of us have become obsessed with finding out as much as we can about Fort Rice. One day last fall I was sorting through the SHSND curator’s correspondence files from 1906-1915, working on research completely unrelated to Fort Rice.

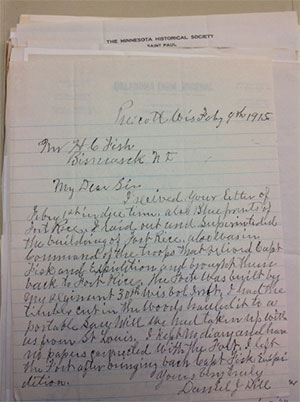

Then, I randomly came across this amazing archive!

Letter from Col. Daniel J. Dill, commander of the 30th Wisconsin Vol. Infantry, to SHSND Curator H.C. Fish. The letter, dated July 4th, 1915, reads, “My Dear Sir, I received your letter dated February 1st in due time, also blueprints of Fort Rice. I laid out and superintended the building of Fort Rice. Also was in command of the troops that relieved Capt. Fisk and Expedition and brought them back to Fort Rice. The fort was built by my regiment 30th Wis. Vol. Inft. I had the timber cut in the woods hauled into a portable sawmill we had taken up with us from St. Louis. I kept no diary and have no papers connected with the fort. I left the fort after bringing back Capt. Fisk Expedition. Yours very truly, Daniel J. Dill.” SHSND Series 30205, Curator’s correspondence, 1907-1923, Box 1, Folder 1915.

This was a letter written to our curator at the time, H.C. Fish, by Colonel Daniel J. Dill, who built Fort Rice. Yep, that’s right. One of Doug’s questions had been related to where the sawmill used at Fort Rice had come from. Now we know. I wish I could have seen Doug’s face when he opened my email attachment that day!

A Found Collection?

Last summer, some of the Museum Division’s interns were inventorying collections we stored at an off-site storage facility. They notified our staff that they had found some wooden posts wrapped in newspapers and stored in crates that appeared to be archaeological. We went to retrieve them in June, and they were in bad shape. What’s more, no one could say for certain where they were from. After putting them through a couple freeze-thaw cycles to ensure no insects would try to hitch a ride into our collections storage space, Collections Assistant Meagan Schoenfelder and I donned our masks and gloves and began documenting all nine of them.

One of nine earthlodge post fragments discovered unexpectedly at an off-site collections storage facility.

We noticed they were wrapped in newspapers that dated to June and July 1950. A couple of them had notes stating they were from Fort Berthold Village (also known as Like-A-Fishhook Village, the last traditional earthlodge village of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara people), but most of them had no attached information. I dug out an old report from my files, documenting the first excavation of this site.

The 19th century village of Like-A-Fishhook, the last traditional earthlodge village of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara people. SHSND Archives 0088-023

On the first page it states, “On June 13, 1950, a party of five Bismarck Junior College Students -… under the direction of Glenn Kleinsasser, graduate student at the University of Michigan, began work on an archaeological project at the Fort Berthold Village site.”[i] The project dates correspond with the newspaper dates. Furthermore, the posts with notes attached only refer to Excavation Units #1, #2, and #3, which, according to the report, are the only numbered units that were tested during that summer. I can’t say for sure that these posts are from the 1950 Kleinsasser excavation, but this information is a pretty good start!

An Unexpected Donation

We occasionally have members of the public drop in with artifacts they have found on their land. Often they want to know what type of artifact they have and how old it is. Most frequently, people bring in something called a grooved maul, which is a type of stone hammer used for thousands of years. They are really neat, and common across North Dakota.

One afternoon I was called to the front desk to look at some artifacts that a gentleman had brought in. I headed to reception, expecting to discuss grooved mauls.

When I got there, there was not a grooved maul in sight. Instead, he had a complete, exhibit-quality stone atlatl weight (!!!!) (very rare – we only have about four in our entire collection), and diagnostic knives and projectile points from every major cultural period in North Dakota between the Paleoindian period (9500-5500 BC) and the Plains Woodland period (400 BC – 1200 AD)! He collected them from his land over many years. I was speechless. All were generously donated to our collections.

Left: A stone atlatl weight, which was fastened to an atlatl (or spearthrower) to increase velocity and accuracy of the spear when thrown.

Right: an Archaic-period knife, with evidence of heavy patination (chemical weathering) on the surface. Patination takes about 1500 years of exposure to the elements before it develops.

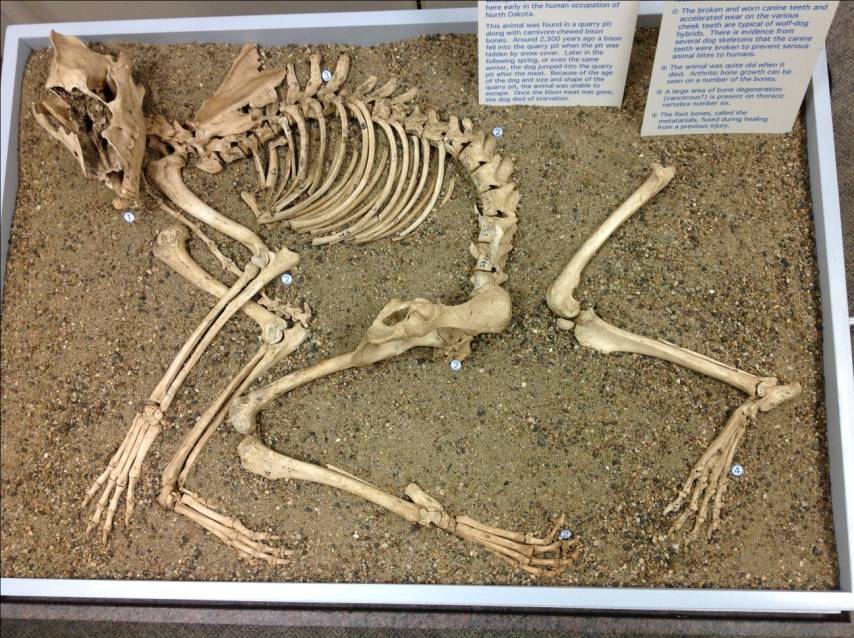

I don’t have the space to tell you about the surprise moose skeleton (!) that was donated to our faunal comparative collection, the surprise guests that came to the lab one afternoon (Governor Dalrymple and First Lady Betsy Dalrymple), or the surprise box of gorgeous LeBeau Ware (post-1500 AD) pottery rims from North Dakota that the Kansas Historical Society found in their collection and donated to us a few months ago – just in time to be included in our new ceramic comparative collection!

So there you have it. As an archaeologist who works with collections, organization, predictability, and efficiency make me unapologetically giddy. But this is also where the unexpected lives, and (most of the time) I like it that way!

I hope your 2015 is full of good surprises.

[i] Kleinsasser, Glenn. Report on the Excavations at the Fort Berthold Indian Village Site. Manuscript on file at the State Historical Society of North Dakota Archives.