Bringing Baby to Work: The SHSND Infant-at-Work Program

“I loved the Infant-At-Work Program so much that I brought both of my sons to work! My favorite aspect about the program was being able to bond with my babies after my maternity leave was over. I felt so fortunate to be able to contribute to my professional career and see my sons every day!” - Emily Ergen, SHSND Archives Specialist

This post will take you way behind the scenes, to talk about the tiniest members of our staff. Many people are not aware that North Dakota state agencies have an “Infant-at-Work Program” (IAWP). I don’t know how it works for other agencies, but I have benefited from it myself at the SHSND and thought the blog would be a good way to share about how it works here.

Tom Linn (Architectural Project Manager) works on his computer while his daughter naps in his lap.

Very simply, IAWP allows new moms and dads to bring newborns to work every day until the child is six months old. YES. I KNOW. Amazing, right? Since I started here in 2011, I have worked alongside at least eight agency babies, including my own daughter. The policy has some caveats, of course – the baby must be in a safe environment, you cannot travel with the baby in a state vehicle, and the baby cannot be at work if he or she is so loud or disruptive that it affects productivity (our administrators make that decision). Parents also need to provide all necessary furniture or equipment like strollers, cribs, changing supplies, etc. So while it is allowed, parents still need to be mindful and considerate. That is not too much to ask, considering what you get in return.

Left: My daughter did not like doing her five minutes of “tummy time” in the office! In a show of solidarity, Lisa Steckler (Historic Preservation Planner) was kind enough to keep her company.

Right: My daughter spent a lot of time in her baby carrier, which allowed me to type with both hands!

So now you might be wondering – how could anyone get any work done while they are also taking care of a baby? It’s a great question. I asked myself the same thing before I started bringing my baby to work. I was so nervous that having her at work would be stressful or affect my productivity (or that of my coworkers). But newborns mostly sleep, snuggle, observe, and eat for the first few months, all of which are things they can basically do anywhere. Don’t get me wrong – working with a baby is hardly easy. But I did learn how to type softly so I didn’t wake her if she was asleep on me, find quiet places to read my work out loud so she would be entertained, and we went for walks through the galleries when she got restless.

Here is Genia Hesser’s (Curator of Exhibits) daughter learning the ropes of exhibit development in the Exhibit Production room.

Usually my job is varied enough that I can do things while moving if she is in an active mood, or sit at my computer and get other things done if she is feeling content. We got into a good groove after a few weeks, where I could predict the best times during the day for me to schedule meetings, eat lunch, do standing work, make phone calls, and so on. And when you do start noticing that your baby is more active and needs more of your attention, you are typically at that 6-month mark, when it is time for him/her to “resign” from the job anyway.

Left: Visitors to our administrative offices may or may not have noticed this little lady on the floor behind Ashleigh Miller’s (Administrative Assistant) desk! She was Ashleigh’s sidekick in answering the phone, assisting visitors, and keeping track of our leave balances.

Right: Here is another SHSND baby helping Erica Houn (Administrative Officer) with payroll and accounts.

Our agency converted our former first aid room to a nursery, complete with a rocking chair, soft lighting, refrigerator and private bathroom. There was never a shortage of co-workers willing to hold her, talk to her, or take her for a walk. In our building, you typically see a baby traveling with an adoring entourage around 10 a.m. or 3 p.m. every day, as people take their work breaks. It gives parents a rest and gives the baby plenty of social time with agency staff. My coworkers were also great about opening doors for me, carrying some of the ten bags I always seemed to have hanging off of me, and looking at me with sympathy rather than irritation when my baby cried.

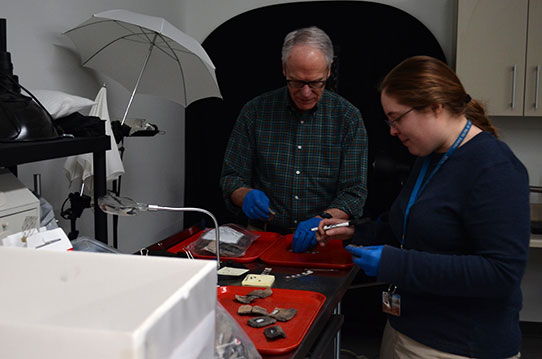

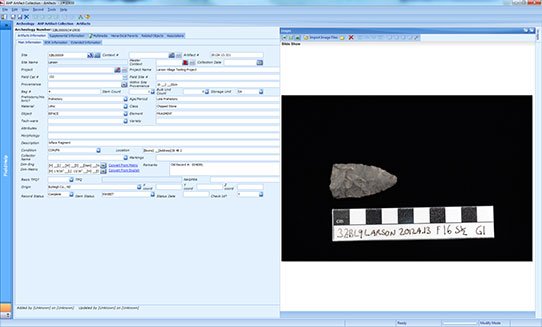

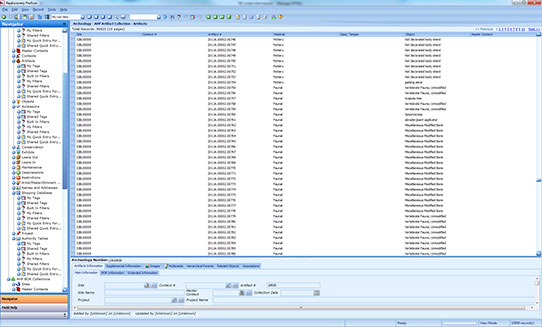

My baby attended dozens of meetings in her first six months, saw her first artifact before she could eat solid food, did some exhibit planning, supervised my work on the lithic comparative collection, and helped me organize countless collections from her stroller or baby carrier. She was an attentive and agreeable sounding board, who always seemed to think that my ideas were great. Our staff even threw her a “retirement party” on her last day of work.

This was my version of a cubicle-nursery in 2014.

As a parent who has benefited from this policy, I am eternally grateful for it for so many reasons. First, I felt like I could enjoy my maternity leave, since I knew that the end of it did not mean the end of being with my baby all day. I was able to bond with my daughter for her first six months, with no disruption in feeding routines or constant worrying during the work day about how she was doing (which I would definitely do) . Second, she grew accustomed to being able to sleep through ANYTHING (and it stuck!).

And lastly, it made me feel a sense of support in the workplace that I have not had anywhere else. Whether it was our Historic Preservation Planner getting on the floor to do “tummy time” with her, our Grants & Contracts officer watching her while I attended a meeting, or our reference specialist mesmerizing her with sparkly things while we talked about historical records, I was never made to feel like my baby was an intrusion. She was just part of the team, and our Security guys even made her an SHSND name badge to prove it. So the next time you see one of us with a baby at the North Dakota Heritage Center, you will know that he or she is part of a tiny army of future historians who were lucky enough to get their start at the State Museum.

Amy Munson (Grants & Contracting officer) was the first parent in our agency to take advantage of IAWP by bringing her son to work in 2006. Thanks for leading the way, Amy!