It’s the Little Things: Exhibiting Small Collections with Artifact Photography

As someone who is tasked with increasing public access to our archaeological collections, here is one of the biggest challenges: some artifacts are very small, while exhibit cases can be very big. In fact, archaeological artifacts that tell some of the biggest stories about North Dakota’s past can be measured in mere centimeters. When our average visitor might spend less than 20 minutes in an entire gallery, chances are high that the smallest artifacts could be overlooked.1 In a museum that comprises five galleries, thousands of displayed artifacts, dozens of tech and media installations, and tens of thousands of words of interpretive text — how do you help visitors appreciate some of the smallest representations of our state’s history?

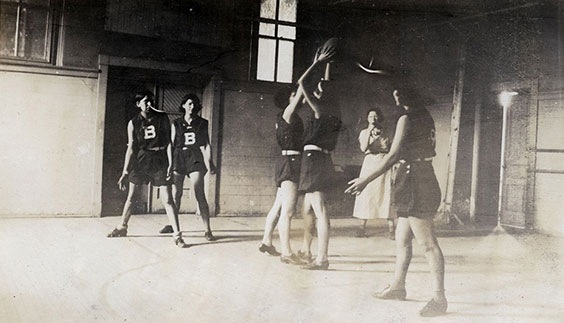

The first installation of the Small Things Considered artifact photo exhibit, 2016.

When confronting this challenge in 2016 while planning for the 50th anniversary of the National Historic Preservation Act, we opted to display these collections in the form of a photo exhibit. Titled Small Things Considered, the exhibit featured 12 large (11”x17”) color photos of archaeological objects. The exhibit was a hit, and ended up being an effective way to give some of our smaller collections the spotlight. So we decided to plan another one for 2019!

Putting together this exhibit is a team effort. First we need the go-ahead from the Audience Engagement & Museum Division, which schedules exhibit spaces. Once the space is secured, our division director and collections staff brainstorm about what unique or interesting artifacts we have come across lately. Then we either find photos we already have of that object, or we take new photos. Sometimes we find an artifact that is amazing to look at, but we can’t include it — because we don’t know enough about it to write an informative caption, or we feel that it needs more context than this type of exhibit allows. Other times we might find an artifact we know a lot about, but we don’t include it because it doesn’t photograph well, is too big, or we have a similar example on display elsewhere in the galleries. This time around we started out with more than 20 photo possibilities, narrowed it down to 14, but couldn’t get to 12. They were all too good, so we just bought two more frames!

Bone toothbrush recovered from Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer’s home at Fort Abraham Lincoln, ca. 1872–1876. The holes in the head of the toothbrush would have been filled with tufts of animal hair, usually boar bristles.

While our collections assistant Meagan processes the photos, I start researching each object so that I can write the captions. This is the best part.

I have mentioned before that we manage millions of artifacts, so we always have a lot to do. There are a lot of emails, digital records, databases, paperwork, and phone calls involved in managing a collection this size, which means that there are many days that I do not handle a single artifact. But this exhibit project affords me the luxury of focusing on one artifact at a time. I have always considered it a privilege to take care of these objects, and I take any opportunity I can to get to know each one of them better.

There are objects that I initially think I am not interested in (e.g., coins come to mind), but after a few hours of research, I find myself talking to anyone who will listen about the history of the nickel or the miracle that is a fish scale. And if I am being honest, not all of this is rosy — I also spent an afternoon tearing my hair out trying to identify the Tiffany & Co. design on a silver spoon (extra challenging when the handle — the most identifiable feature of an historic spoon — is completely missing).

My typical approach is to write captions that are too long, because I can’t bear to leave out any of the interesting information I found. Then our curator of exhibits and our editing team rein me back in, and we miraculously condense this research to about 50 words per artifact. Our division director gives final approval on photos and captions, and the rest is up to the exhibit installation team. Here are a few highlights:

1. 1866 Shield Nickel

I’d like to introduce you to my new favorite nickel, which dates to 1866 and was found near Fort Rice. The rays around the “5” were believed to have complicated the striking process when these were minted. The coin’s design broke the dies or resulted in a coin whose features were not as sharp in relief as they should have been. For these reasons, the rays were removed from the design in 1867. This object represents a shift in minting practices after the Civil War.

An 1866 Shield Nickel, the first 5-cent piece to be made from a nickel-copper alloy.

2. Clay Horse Figurine

While researching the clay horse figurine from the 19th-century site of Fort Berthold pictured below, I came across a historic photo that explains who likely made it. It closely resembles the clay figurines made by students at the Fort Berthold Indian Mission School during the 1870s. Note the detail in the horse’s mane, and the eye on the side of the (broken) face. Another less complete example in the same collection has holes in the bottom, which appear from the historic photo to have been used to insert small twigs for legs. The founder of the mission (1876), Charles Lemon Hall, learned all three languages (Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara) spoken by the students who attended the mission school.

Clay horse figurine from Fort Berthold, ca. 1870s.

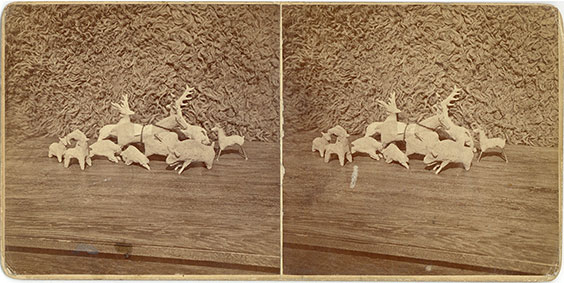

Stereoscopic image of clay or mud animals made by Native American boys at the Fort Berthold Indian Mission School, ca. 1870s. Photo by O.S. Goff. (State Archives 00088.0031)

3. Olivella shell bead

The shell bead pictured below is about ¾” long. In a typical exhibit case (which is about the size of a small closet), its details might easily be overlooked when surrounded by larger or more colorful objects. But in this picture, you can see that the pointed spire at the top has been lopped off, which creates a hole through its body. You can also see the variegated color near the top, and the texture of the whorl. These Olivella shells (Olivella dama) are from the Gulf of California and made their way along trade routes to North Dakota. The presence of Olivella shells in this region demonstrates the extent of trade networks between Native groups long before Europeans arrived.

Olivella shell bead (Olivella dama) from McLean County

It is important to display artifacts in the context of where, when, and with what other objects they were found, and our exhibit cases achieve that. The context of an artifact tells the story. This photo exhibit does not diminish the importance of context, but rather brings the beauty and details of individual objects into focus. Stop by the Merlan E. Paaverud Jr. Gallery outside the auditorium the next time you find yourself at the North Dakota Heritage Center & State Museum, and see for yourself!

1Average visitor time tracking statistics can be found in Exhibit Labels: An Interpretive Approach by Beverly Serrell, 1996, AltaMira Press.