Last week, I published a post on how to conduct photo orders in the State Archives (if you missed it, find it again here). I promised I would follow up with a second post on how to use this information to place a photo order, how these images can be used, what we do and do not allow, and more.

So, here we go again!

As you learned in my previous post, quite a few photos can be viewed and accessed on our website. We are happy that these items can be used and viewed in this way, as it does help people researching images. But, how do you actually get the image? And what are you able to do with it once you have it?

Ordering Images

Images provided by us are part of our collections, and if we need to provide a copy, we do charge a fee.

At this time, you may order one of four types of images.

1. A watermarked thumbnail for reference, which is typically scanned at the lowest resolution with the agency name stamped across it. This is for reference to show you what is in an image that heretofore has not been scanned or posted on Digital Horizons. We do not charge for this service. (The watermarked image shown here is SHSND 10468-00357).

2. A paper print, which is typically black and white ink on white paper. For a paper printout, the clarity of the image is pretty good, but this is printed on regular printer paper, and again is just intended for research purposes. The fee is $1 per image.

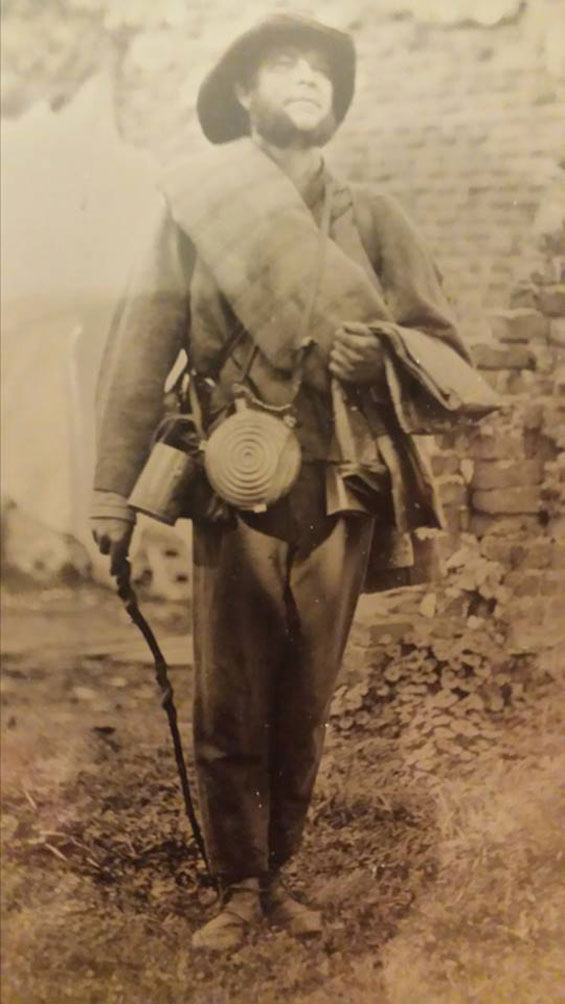

3. A low resolution scan of the print or negative, such as the image shown here of President George H.W. Bush in Bismarck during the Centennial Celebration in 1989, SHSND 31843-016-00002. (The images used in our blog posts are all low resolution.) This is typically provided in a jpg format and is sized around 200 dpi or less. This indicates that you may see less specific detail, and enlarging the image makes it more pixelated. This image can probably still be sent to you in your email as an attachment without filling your inbox—kind of similar to most normal or lower resolution photos you might take on a smart phone. The fee is $8. If it suits your needs, you can download images from Digital Horizons. They are about the size of a typical low res scan, and we do not charge you for this service.

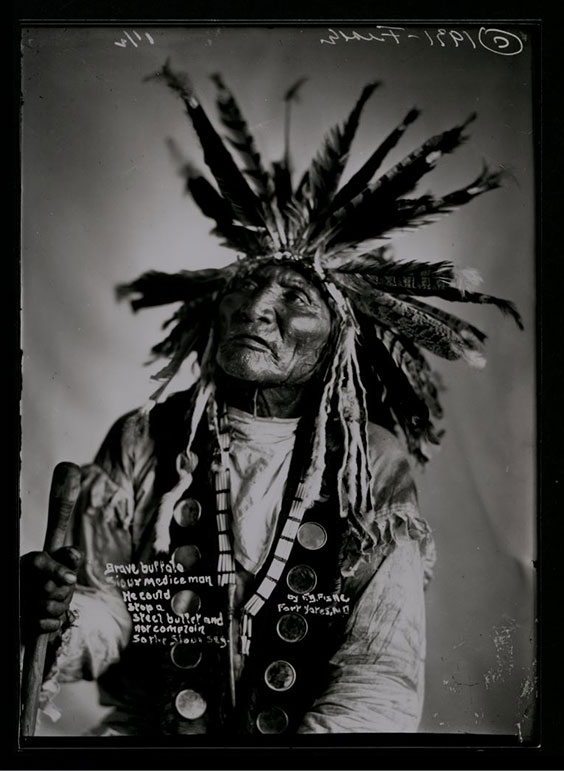

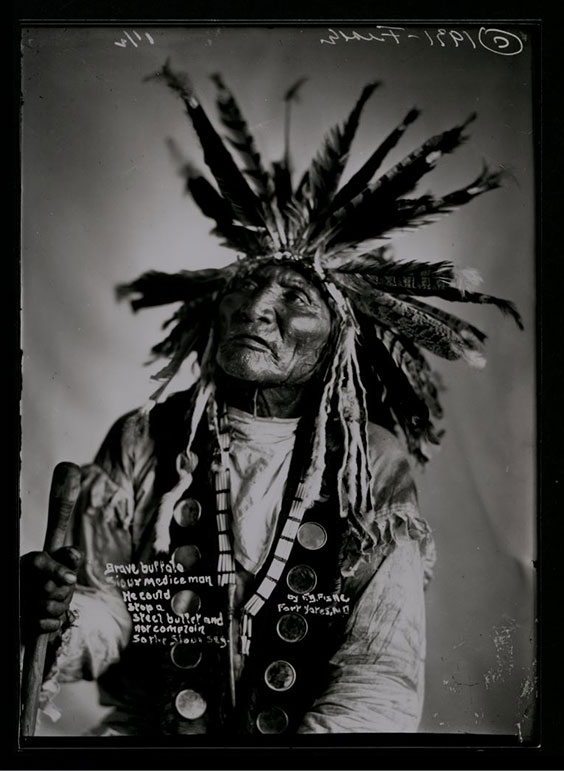

4. A high resolution scan of the print or negative. This image is probably too large to send to you as an attachment, and will likely need to be sent to you via our share site or on a disc. These comprise the majority of the photo orders we fill. They are typically sized around 600 dpi. These images are crisper, clearer, can be enlarged easier, and are considered suitable to print. Though we are capable of scanning items at a higher setting, this is typically the standard. (You can see this in this detail from photo SHSND 1952-05018, a photo by Frank Fiske of Brave Buffalo. The details of his face are still very clear and crisp. A high resolution scan fee is $20 per image.

If you want to order an image, come to the Archives in person or email or call us with the photo information. We may ask you to fill out our order form, available here on our website. Often, an email with the photo number is plenty.

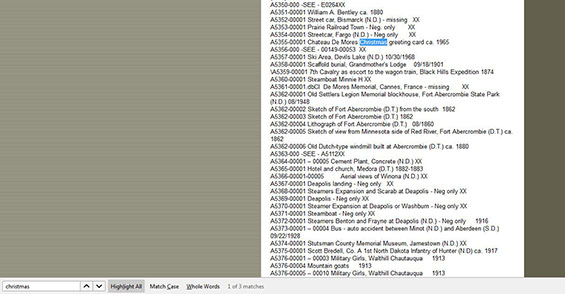

The photo number consists of a collection number and item number (although letters are occasionally part of the name). They sometimes are longer and shorter, depending on what they are a part of. However, they typically look like one of these examples:

1952-00001 → 1952 is the collection, and this is the first item in that collection.

2005-P-001-00001 → 2005-P-001 is the collection, and this refers to the first item in that collection.

A0002-00001 → A is the collection; there are a series of linked images in this collection so while there may be several item numbers under this second item in the A collection, this is the first image.

10958-31B-25-00001 → This is the first photo in folder 25 of Box 31B from manuscript collection 10958 (William Shemorry). Not all manuscript numbers are as long as this one, which does differ slightly in its numbering. Most will look like a typical photo collection number and item number.

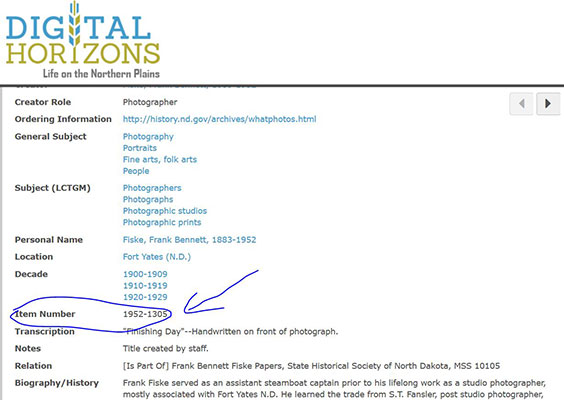

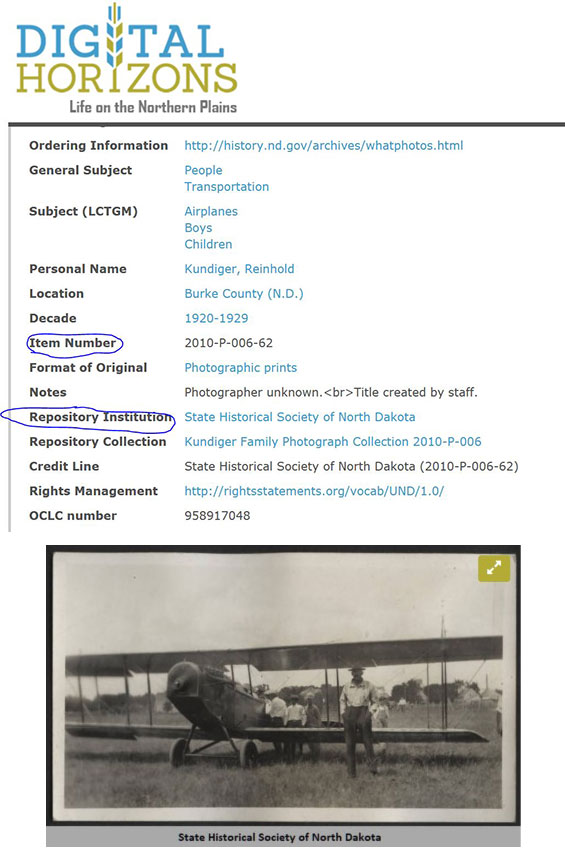

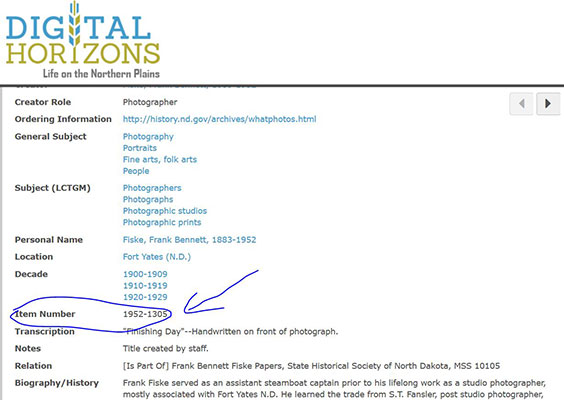

Find the photo number on Digital Horizons by scrolling down the page and selecting the item number (circled).

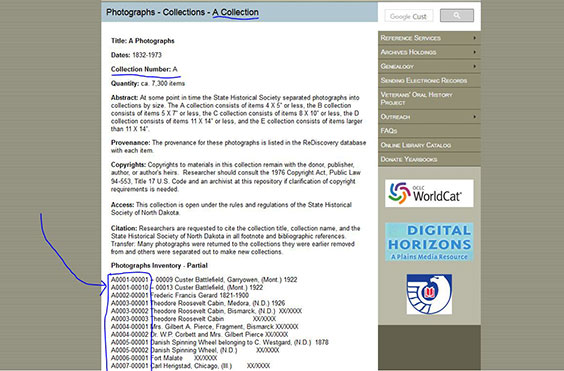

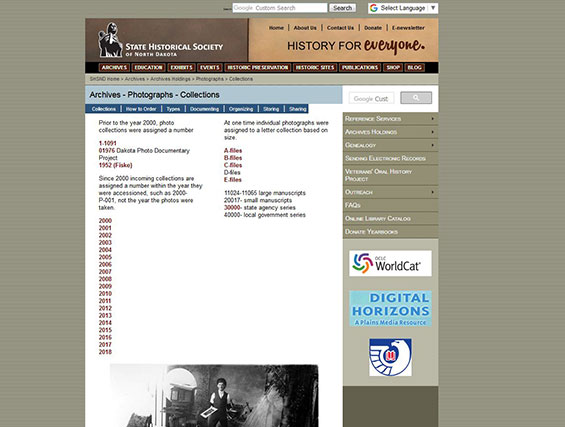

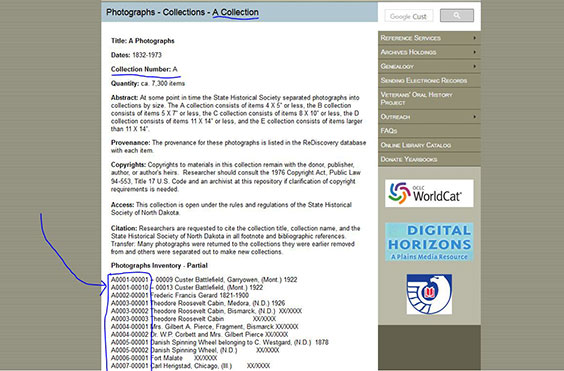

If you want to order an image that is not on Digital Horizons, you’ll need the photo number on our website. If the image itself is posted, this number will be found near or underneath it on our webpage or even on our Facebook posts. The photo numbers are also listed out under the photo collections, where you will see the summary of what is in the image (as in the picture below).

Once you have found this number, you can email us at archives@nd.gov (this is the preferred method), call us at 701.328.2668, or bring or mail the order form to State Archives at 612 E Boulevard Ave, Bismarck, ND 58505. You can send these orders to my attention.

We require prepayment for photo orders, so don't be surprised if you must make your payment before you get to see the image. Once your order and payment are received, we prepare your images. Typically, they are completed within two to three weeks, but this time can vary, and it may be more or less time to complete a photo order.

Using images from the State Historical Society

While you may obtain photos from us, neither copyright nor ownership is transferred to you. These photos remain part of our collection, and copyrights remain with the donor, publisher, author, or author's heirs. So we do have rules governing use of our collections.

1. Most, but not all, of our images are available for purchasing copies and for use.

2. Images must be used respectfully. They cannot be altered or rearranged in any way (although you can use a detail of a photo and mark it as such).

3. Personal use allows images to be used privately, for personal means, or for research. No use fees or forms are required for this use beyond the original scan fee.

4. Public use means an image is used in a public area and/or potentially for profit, such as display in an office, store, restaurant, or similar building; publication in a book; or use in a documentary. This use requires patrons to fill out our one-time use form. Fees for this use are listed on our website.

5. Online use is allowed in specific ways. Images that may be posted online should be used in low resolution. If an image is posted on Facebook or a blog post or on a personal site, it must be cited as from the State Historical Society of North Dakota plus its photo number. Use fees are variable, but typically use fees are waived for online use. We may require users to fill out our one-time use form.

6. All images must be cited as being from our agency and show the full photo number. (State Historical Society of North Dakota 00001-00001 is an example citation.) This is for public use, but it is helpful to retain this number for people interested in obtaining an image for private use as well.

7. We do not allow State Archives images to be reproduced on clothing, or reproduced and sold in any other way.

Just remember, if there are ever any questions on photo use, we are here to help! Feel free to contact us at any time.