SHSND D0692. World War I Draftees shown in front of a building.

SHSND 21085. Harvey Hopkins is shown in a World War I uniform. Picture taken circa 1917.

These past few months, we have seen an uptick of researchers in the Archives looking for information on World War I. This is at least partially because we are currently a century out from the Great War, as it was known at the time. An event that is so widespread and life-altering across the world evokes curiosity, reminders, and memorials.

You might think we would not have a ton from World War I in our archives, and in the grand scheme of things, it’s true that it is not our largest grouping of collections. However, we are a state entity archiving North Dakota history, and many North Dakotans served and saw battle, or pinched and saved and donated for the cause. The Great War impacted everyone, including North Dakota. Therefore, we have some collections related to it.

SHSND 10935 P014, 10935 P345, 10935 P149. Several posters from our WWI collection.

One of our most popular World War I collections, #10327, consists of four scrapbooks of letters from soldiers that were printed in various newspapers from 1918 to 1919. These oversized books contain a plethora of snapshots into a different past, allowing soldiers to share details of their daily lives and experiences in their own words.

We also have collections that deal partially with World War I. Collection #10107, for example, contains some correspondence to and from Hazel Nielson o ver several decades. This includes letters from Hazel to her family and friends while she stayed in Europe during World War I.

We also have one of the largest collection of WWI and WWII propaganda posters in the country. This is because one of our past curators, Melvin Gilmore, felt that the war posters documented such an important piece of our history, he needed to save them. He sent out a call for these documents, and received them from all corners of the world. As a result, we have war posters that are in multiple languages and in different conditions. Some are pristine, some are well-used, and all paint an interesting picture of the attitudes at the time of the war.

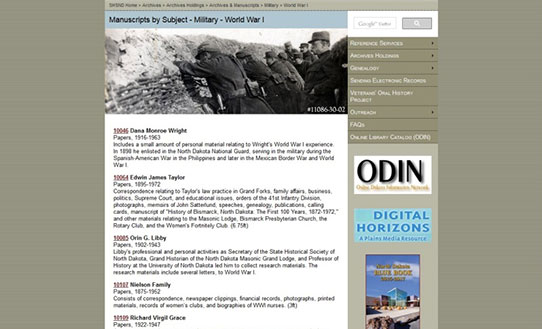

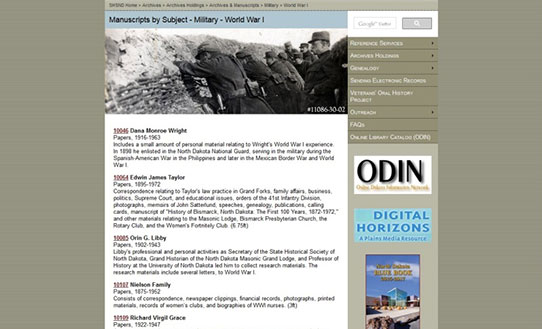

A screen shot of the WWI page on our website.

More books, documents, and photos can be found searching our website through ODIN, our online database. You can also venture off our website, looking through Digital Horizons, or even skimming through collections we have earmarked as related to World War I on this web page.

This year, as part of the curriculum of Dr. Joseph Stuart’s Great War class at the University of Mary, we were lucky enough to have about 20 interested and excited young men and women visit the Heritage Center and the Archives to research different facets of World War I. The class was composed of college students of different ages and interests, and developed into a cross-discipline event. Some researched war propaganda; some researched specific individuals who served; some researched the components of the mustard gas used in warfare.

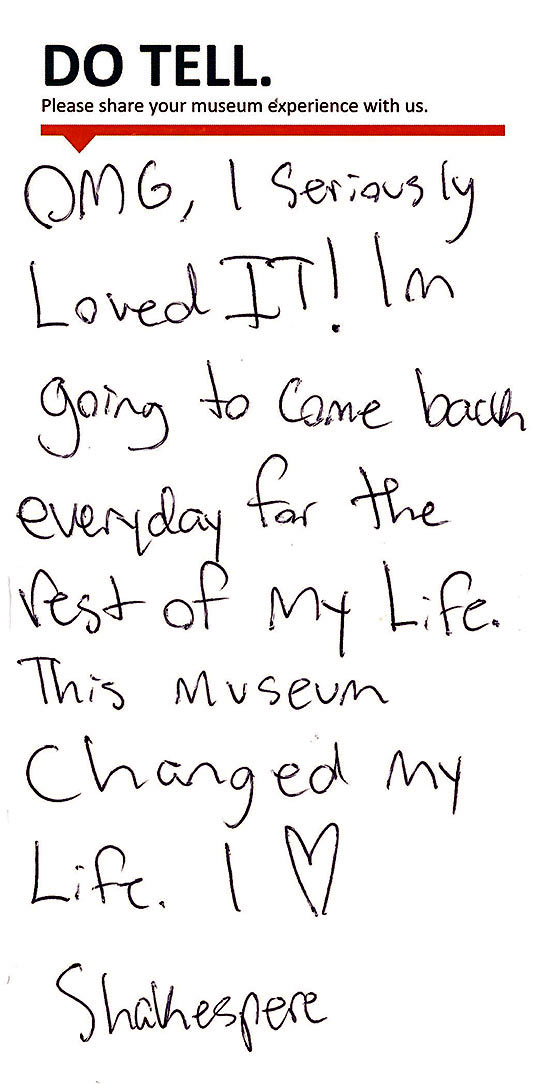

Many of the students in the Great War Class at the University of Mary had never been inside an Archives before, and did not know what to expect. They came as a class multiple times, and some continued to come individually. We showed them around our Reading Room and showed them how to use our websites to locate these collections, and then they were free to discover their truths. They were kind and courteous and so excited! Their instructor informed me that at the start of every class, they started talking about what they were researching, what they were learning.

This sort of collaboration is a really cool and different way that we can help new and continuing researchers. It was incredible to watch these eager young adults work, learn, and grow as they developed their research, and as they began to understand what people went through just a century ago.

The Great War was terrible in many ways, but it is helpful to study it and learn from it, for all generations. We are lucky to be able to provide that service, and to see students use our collections to bring new knowledge and perspectives to an old story.

KFYR photo. One of the students worked at our local news station, and put together a report that aired on local news channels of the work they were doing, still available to read on this page.

Many of the students in the Great War Class at the University of Mary had never been inside an Archives before, and did not know what to expect. They came as a class multiple times, and some continued to come individually. We showed them around our Reading Room and showed them how to use our websites to locate these collections, and then they were free to discover their truths. They were kind and courteous and so excited! Their instructor informed me that at the start of every class, they started talking about what they were researching, what they were learning.

This sort of collaboration is a really cool and different way that we can help new and continuing researchers. It was incredible to watch these eager young adults work, learn, and grow as they developed their research, and as they began to understand what people went through just a century ago.

The Great War was terrible in many ways, but it is helpful to study it and learn from it, for all generations. We are lucky to be able to provide that service, and to see students use our collections to bring new knowledge and perspectives to an old story.