Return of a Japanese Good Luck Flag

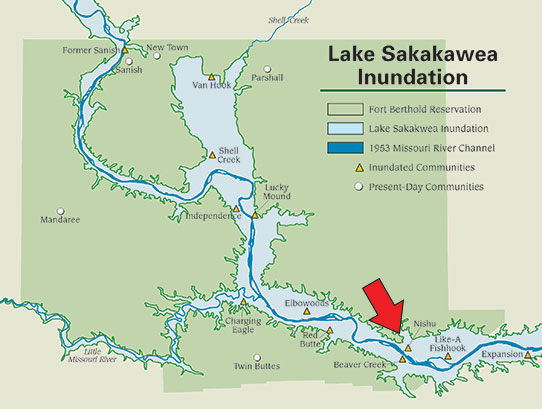

PAR-2016015 Japanese WWII Yosegaki Hinomaru, good luck flag.

A Japanese flag (PAR-2016015) and a piece of wood with Japanese writing (PAR-2016085) were unaccessioned items recently found in the museum collections storage area (see Lost and Found in the Collections). Lacking any documentation or provenance on these items and with similar, well-documented objects already present in the General Collection, the Museum Collections Committee declined the objects for the collection. After careful deliberation, the committee determined the best route for these objects would be to turn them over to the Obon Society. The Obon Society is a nonprofit organization that specializes in the repatriation of war prizes taken from Japan during World War II. They specifically focus on the repatriation of Good Luck flags, Yosegaki Hinomaru. Before leaving home, it was common for a soldier’s family and friends to write well wishes and to encourage bravery in battle on a small Japanese flag. The flag was then presented to the soldier and the soldier carried the flag with him throughout his time in the war. It was believed that the Yosegaki Hinomaru held a power with their messages that would watch over the soldier and see him through difficult times.The Yosegaki Hinomaru were popular war prizes among US soldiers, and many flags were taken from Japanese soldiers and brought back to the United States. We currently have 3 Yosegaki Hinomarus in the Society’s collection. Now, many veterans and family members of WWII veterans are returning these flags and other war prizes back to Japan. The flags hold deep meaning for Japanese families. For many families, these returned war prizes are the only remains of the soldier they will ever receive.

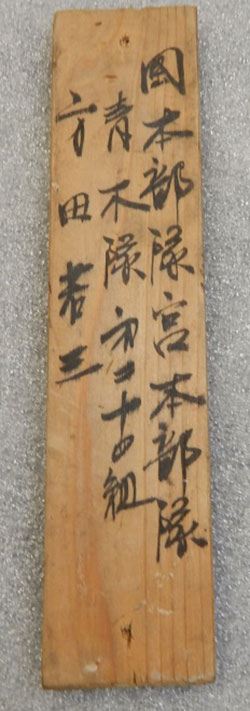

PAR-2016085 Wooden plank with identification information written in Japanese.

Although the Obon Society focuses most of their efforts on the good luck flags, they accept other personal items that were taken from Japanese servicemen including diaries and letters. For this reason, we also transferred the piece of wood with writing on it to the Obon Society. The writing on the wood gives identifying information, similar to the kind of information that would be on a military dog tag. Hopefully the Obon Society will be able to trace the name written on the wood to a living family member.

The Obon Society is not always successful in their endeavors, but they try to send all items back to a family member. If that is not possible, they try to find the community the soldier was from and give it to a community center, local government, or even a local shrine.

The Obon Society believes that returning these war prizes is an exercise of goodwill and friendship between two nations and a symbol of reconciliation. It can bring closure to families both in Japan and the United States. The Obon Society’s work has been endorsed by the American Embassy in Tokyo, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, and the Japanese Minister for Foreign Affairs. The Museum Collections Committee believed this was an opportunity for the State Historical Society of North Dakota to contribute to a humanitarian cause.

The State Historical Board approved the repatriation action at their October 10, 2016, meeting. The proper paperwork was filled out and the flag and wood were shipped to the Obon Society in November. We have since received a thank you letter letting us know we will be notified when the objects are being researched and whether or not the Obon Society was able to trace the items to the family or town from which they came.

If you would like to find out more about the Obon Society and their mission, visit http://obonsociety.org. You can also learn more from the video, A Peaceful Return.