How Fun Are These? Historical Facts From the State Archives, Part I

Did you know? The North Dakota State Archives staff are full of fun facts about this state’s history. That’s because we work so closely with collections, books, newspaper articles, and other documentation related to the state. When we discover something bizarre, interesting, humorous, or unique, we have the tools to dig deeper, and we love to share our findings. More proof that it’s a lot of fun to work at the State Archives!

Read on for the first installment of our staff’s favorite fun facts about North Dakota.

Ashley Thronson, Reference Specialist

While I have learned many things about the history of North Dakota since I started working for the State Archives, one of the most memorable tidbits was reading about a memorial adopted by the territorial Legislature in 1879 related to the division of Dakota Territory. A delegation traveled to Washington, D.C., where territorial Rep. John Q. Burbank of Jamestown petitioned Congress with a proposal to divide Dakota Territory along an east-west line. Compared to the current north-south division that created the two states of North Dakota and South Dakota, an east-west split would certainly have been different! This fact also got me thinking of how the territorial divisions impacted and influenced cities and communities. What would Bismarck, Fargo, and other North Dakota towns have looked like in an East Dakota or West Dakota?

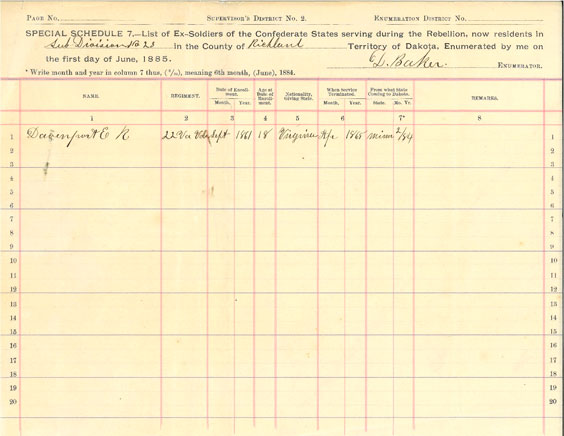

Map of Dakota Territory by district, 1884. SHSND SA 978.402 R186m 1884

Matt Ely, Photo Archivist

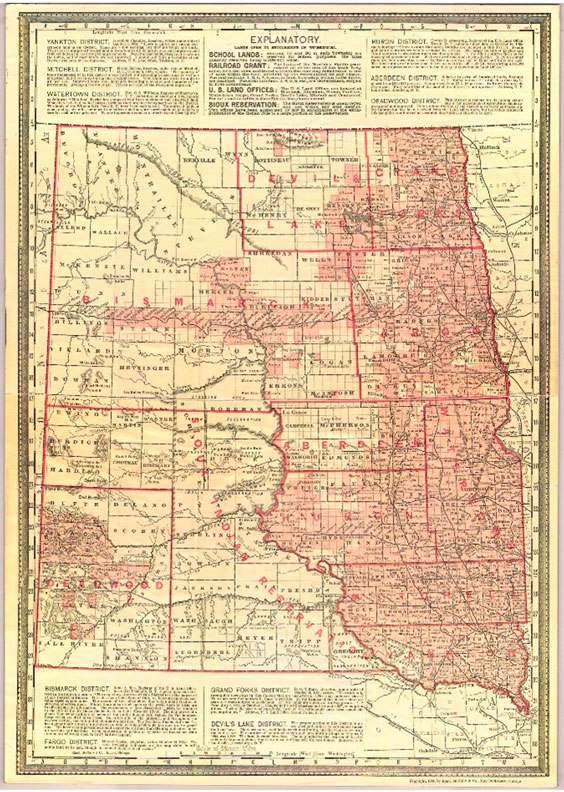

My favorite North Dakota fun fact is that the Ward County Courthouse fielded men’s and women’s basketball teams in 1909-1910. The formation of the teams was announced on Nov. 18, 1909, in the Minot Daily Optic. The State Archives collections include a picture postcard of the men’s team. Although I have been unable to find the team’s schedule yet, a note on the back of the postcard states that they had a record of five wins and zero losses going into their final game against Minot High School. In the future, I hope to find the result of their final game as well as any information I can on the women’s team.

The men’s basketball team from Minot was commonly referred to as the Court House basketball team, as evidenced in this image, circa 1909. SHSND SA 2006-P-012-00015

Lindsay Meidinger, Head of Archival Collections and Information Management

In 1911, a standpipe and tank were built on the North Dakota Capitol grounds in Bismarck. This water tower was witness to historical moments during the formative years of the state, including the 1930 Capitol fire. Recently, the State Archives received a donation of a photograph of the new capitol building. In the background of the image, the same water tower is visible. Utilizing the State Archives’ online resource, Advantage Archives, we learned that the water tower was “unriveted and taken down” in 1957. Not only was the date it was disassembled discovered, but we also found out that the water tower was sent to Hannaford for its first municipal water system. And it still stands there today!

The water tower looks on as the original North Dakota Capitol burns, December 28, 1930. SHSND SA A3522-00001

Jayne and Sally Strawsine on the North Dakota Capitol grounds in 1948. Notice the water tower to the right of the Capitol building. SHSND SA 11567-00004

These days you’ll find the original state Capitol water tower in Hannaford.