Digitizing Archaeological Collections: Advancing Research, Preservation, and Data Management

Archaeology collections management involves organizing and systematically caring for archaeological artifacts, specimens, records, and associated materials. Proper management is crucial to ensure the preservation, accessibility, and long-term research potential of these collections (Knoll and Huckell 2019). Maintaining high-quality curation standards goes beyond storage enhancement and environmental monitoring. It involves meticulous organization, comprehensive documentation, and secure storage to bolster preservation and ensure accessibility of collections for research and educational purposes. The primary goal driving artifact inventory, accessioning, cataloging, and curation is to maximize the research potential embedded within these collections (Allen et al. 2019; Benden and Taft 2019; Thomson 2014).

Digitization facilitates efficient data management by creating digital records that can be easily organized, searched, and linked. This simplifies collection management, cataloging, and information retrieval. Digitized artifacts enable precise identification, tracking of location and loan status, and documentation of their condition and preservation requirements (Graham 2012; Thomson 2014). “Organizing objects digitally within a collections management system simplifies inventory processes, ensures effective storage and tracking of all items, and guarantees convenient future access,” according to Thompson (2014: 53). This digital approach significantly enhances the handling of substantial volumes of material (Graham 2012; Thompson 2014).

Moreover, digital access to collections allows for more extensive and efficient research, analysis, and comparison of artifacts. Digital records enable the seamless integration of various data types, including images, texts, and metadata, within comprehensive databases. This integrated approach empowers researchers to establish connections and correlations (Benden and Taft 2019; Thomson 2014). Digitization encourages data sharing and collaboration among archaeologists, researchers, and institutions, leading to more comprehensive research and discoveries. It streamlines data retrieval and expands collection accessibility for scholars, educators, and the general public (Graham 2012; Thomson 2014).

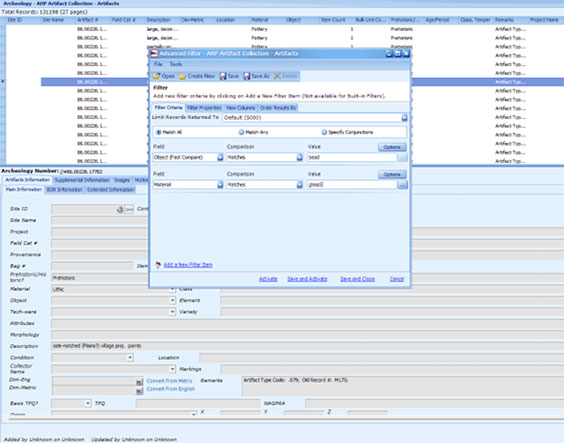

The archaeology collections team within the Archaeology & Historic Preservation Department utilizes the Re:discovery Proficio Collections Management Software to digitize, manage, and organize a wide array of collections, including artifacts, ecofacts (e.g., fauna, flora, pollen, and soil found at archaeological sites), specimens, and documents. Since implementing the software, over 136,000 artifact records have been digitized within the archaeology artifact modules. Beyond cataloging and inventory management, the software provides advanced search functionalities and customizable data fields to efficiently organize items based on diverse criteria. Proficio also facilitates monitoring item conditions and conservation efforts and supports user access control for data security.

In sum, digitizing archaeological collections is a highly valuable approach that enhances accessibility, preservation, and research opportunities for artifacts. It fosters public engagement and collaboration within the archaeological community. By employing tools like Re:discovery Proficio Collections Management Software, we have digitized thousands of artifact records, paving the way for streamlined organization, efficient cataloging, and comprehensive documentation. In essence, the digitization of archaeological collections isn't just a technological advancement—it's a gateway to preserving the past, enriching the present, and shaping the future of archaeological research and public engagement. However, it's crucial to proceed with care, following best practices to maintain the accuracy and integrity of digital records.

An example of Proficio’s advanced filtering options to search and organize all glass beads from the State Historical Society’s archaeology artifact collections. The total record count for this module is located in the left corner of the display. Sensitive site information has been redacted from the image.

References

Allen, Rebecca, Ben Ford, and J. Ryan Kennedy. 2019. “Introduction: Reclaiming the Research Potential of Archaeological Collections.” In New Life for Archaeological Collections, edited by Rebecca Allen and Ben Ford, xiii-xxxix. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press and the Society for Historical Archaeology.

Benden, Danielle M., and Mara C. Taft. 2019. “A Long View of Archaeological Collections Care, Preservation, and Management.” Advances in Archaeological Practice 7, no. 3: 217-23.

Graham, Chelsea A. 2012. “Applications of Digitization to Museum Collections Management, Research, and Accessibility.” Master’s thesis, Lund University.

Knoll, Michelle K., and Bruce B. Huckell. 2019. “Guidelines for Preparing Legacy Archaeological Collections for Curation.” Society for American Archaeology. https://documents.saa.org/container/docs/default-source/doc-careerpract….

Thomson, Karen. 2014. “Handling the ‘Curation Crisis:’ Database Management for Archaeological Collections.” Master’s thesis, Seton Hall University. https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations/1970.