5 Reasons Readers Love "North Dakota History"

As an editor, I get to geek out over dictionaries, style guides, and book catalogs (such as this one from the University of Nebraska Press). I also try to stay current with a variety of academic journals, and am privileged to work with editor Pam Berreth Smokey on one of the best in our region: North Dakota History: Journal of the Northern Plains, published semiannually by the State Historical Society of North Dakota.

Perhaps you are one of our devoted readers, but for the uninitiated (and newcomers to the northern plains, such as myself), I am excited to tell you about this stellar resource. The State Historical Society loves gathering audience feedback, and we recently conducted a North Dakota History reader survey. Ensuring reader satisfaction is a unique challenge in that we want to present new, credible scholarship in an accessible and visually appealing way.

Well, we were thrilled with the results! Here are five top reasons readers love our journal.

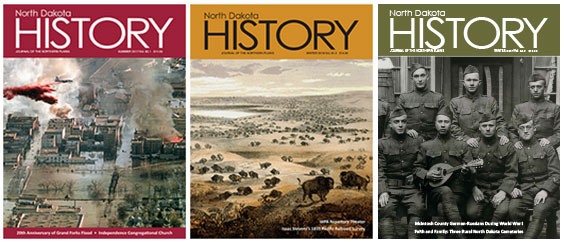

Recent covers of North Dakota History: Journal of the Northern Plains

1. Well-researched articles.

Did you know the State Historical Society of North Dakota has published an academic journal since 1906? While the journal (called North Dakota Historical Quarterly from 1926 to 1945) maintains high academic standards for the historians, professors, and others who contribute well-researched articles, we also attract a broad general readership of folks interested in the history of our region. If we can help the reader think more deeply about an article topic through a new lens or learn a fascinating new tidbit about history, we’re fulfilling our purpose.

2. Enlightening topics.

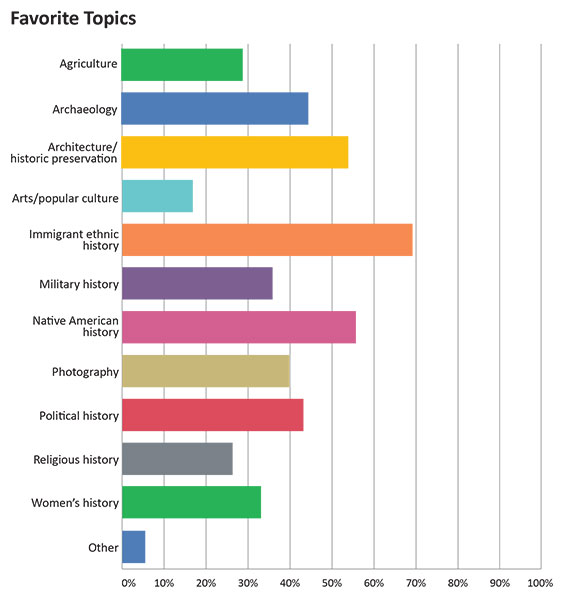

In our reader survey, over half of respondents* rated the journal “outstanding,” and 79 percent read “most pages” or “cover to cover.” As a bookworm (and the journal’s book review editor), I am excited folks still make time to read an entire magazine! Some of the most interesting feedback relates to article topics: immigrant ethnic history is our most popular subject area, with Native American history and architecture/historic preservation coming in close behind.

From North Dakota History reader survey, January 2018

3. Local history is personal.

Our most popular article of 2016–17 was “1997 Grand Forks Flood” by University of North Dakota professor Kimberly Porter, which recounted a personal experience of the natural disaster many of our readers lived through. Similarly, our Winter 2017 issue featured McIntosh County German-Russians and three rural North Dakota cemeteries, meaning many of our readers were tied (as actual relatives, or culturally) to the people and communities discussed.

Kimberly Porter’s article on the 1997 Grand Forks flood was the most popular of the past year. North Dakota History, Vol. 82.1 (Summer 2017), pp. 18–19

4. Great design.

Images remain vital to our storytelling, and we are proud the journal has won the Mountain-Plains Museums Association Publication Design Award for two years in a row (2016–17). The most recent winner included this article on frontier photographer Orlando S. Goff, who captured an iconic photo of Sitting Bull in 1881.

5. One-of-a-kind stories.

On the northern plains, truth sometimes really is stranger than fiction. We continue to add original content for free online, including this recently posted 1957 article, “Reminiscences of a Pioneer Mother.” A personal favorite, Kate Roberts Pelissier’s astounding oral history is reminiscent of Little Women and the Little House books.

Margaret Barr Roberts, described in “Reminiscences of a Pioneer Mother” by Kate Roberts Pelissier, raised five daughters alone on a ranch near Medora after her husband disappeared. SHSND A4454

Have I piqued your interest enough? You can catch up with the contents of recent issues online, read them in our State Archives, purchase copies through our Museum Store, or subscribe. Our next issue, going to press in June, will highlight World War I memorials across the state and explore the 1856 G. K. Warren maps, which were pivotal in charting the Missouri River and its environs.

Keep reading! And don’t hesitate to let us know what you think.

* We conducted the survey electronically through an email to available subscribers. The link was also published in the print journal. Fifteen percent (148 people) of the email list responded.